No products in the cart.

Outdoor Adventure

How to Cook Big Hunks of Meat in Your Backyard

Before bagged charcoal or propane grills, big joints of meat were cooked outside with more elemental materials: burning logs, ashes and coals, hot stones. If you can procure a few easy-to-find hardware-store items, it’s surprisingly simple to re-create a “barbecue” from millennia past. For whole shoulders, whole legs, rib racks, and more, here’s a low-tech, approachable option for primitive cooking in your backyard.

Bury It Deep

Pit cooking and underground ovens were utilized in many ancient cultures, including curanto, which originated in Chile at least 6,000 years ago as a way to cook seafood and vegetables; the Maya pib, which lends its name to cochinita pibil; and the Polynesian imu, an underground oven that’s the vessel for authentic kalua pork, the centerpiece of a Hawaiian luau. What ties them together is how the food cooks underground, surrounded by hot stones. It bakes, it steams, it smokes, and, because all the dirt above it creates a kind of hermetic seal, it almost pressure-cooks, too. The result is something whose flavor is indescribably deep, and which is simply unachievable in a kitchen.

My favorite meat to cook like this is a whole pork shoulder, though it’d be just as good for brisket or even a whole turkey for a memorable Thanksgiving dinner. I like to marinate the pork overnight (a few hours is also fine if you’re in a hurry) in a basic salsa—dried guajillo, ancho, and pasilla chilies reconstituted in stock and blended together with salt, garlic, onion, cumin, coriander, and orange juice—which adds a nice bite and slight bitterness to cut through some of the pork’s sweetness and fat. Pierce the shoulder thoroughly all over with a fork before applying the marinade.

Now the pit. First things first: you’re digging a deep hole and making it really hot, so you need to be positive that you’re not doing this in an area where there are water or electricity lines, a septic field, or anything like that. If you’re a homeowner, check your plat, or even consult your local utility authority. If you’re a renter, ask your landlord. If they’re not jazzed on this idea, save it for car camping, if your location allows. Get to your site in the morning, get your food cooking, head out on a long hike, then come back for the finest camp dinner of your life.

Secondly, make sure the stones you use are thoroughly dry. Anything wet is liable to explode during cooking, so leave the river rocks where they are. I pick up 15 to 20 stones from around my yard: simple, smooth-faced landscaping ones, ranging in size from a softball to a honeydew. You can also find suitable stones at garden centers if you don’t have them around. Most anything will work for this, so long as it’s dense and relatively uniform.

Grab a shovel, and dig a hole at least three and a half feet deep. Line the bottom with your stones, and light a fire on top of them. Once it’s really burning, about a half-hour later, place more stones around the perimeter. Stoke the fire, and keep it going for another hour or more to make sure the rocks are as hot as can be.

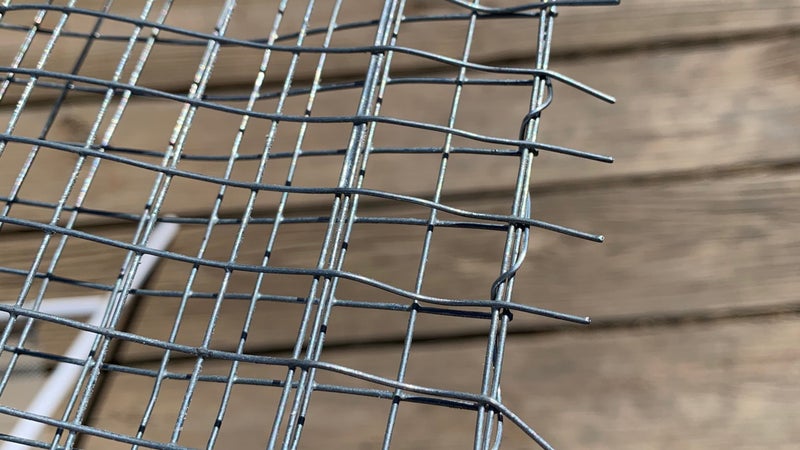

While that’s happening, prep your assembly. I’ve used some steel chicken wire with tight, half-inch gaps to create a kind of tray with which to lower and lift the pork out of the pit: it’s ten feet by two, folded in half lengthways, and then stitched on the open ends with wire. Attach a couple of loops onto each end—using chain, wire, string, whatever—as handles that will stay near the top of the hole.

Almost every traditional pit-cooking method utilizes some sort of large leaves to encase the food and add steam during the process. The most widely available leaf is banana, which is stocked fresh or frozen at most Mexican, Central American, or Asian markets, as well as at a number of online purveyors, including Amazon. Prepare the packaging for the pork by laying it out in reverse: First, put down a cross of heavy-duty aluminum foil, each arm about a foot and a half wide by three feet long. On top of this, lay down long cuts of simple butcher’s twine, a few in one direction and a few in the other, each evenly spaced across 12 or so inches. Lastly, put down several sheets of banana leaf in both directions of the cross, and then work down the assembly: wrap the pork shoulder one way and then the other in the banana leaves, securing the leaves with the twine, and covering the whole thing with the aluminum foil. Finishing it off with the foil will inhibit the amount of smoke that the meat gets, but it does act as an extra safeguard against dirt working its way into the package. If you want a slightly smokier flavor, skip the aluminum foil and add a few more layers of banana leaf.

At this point, the fire should be reduced to mostly embers and hot coals. Dig out about half of the hot rocks from the pit with the shovel, even out the spacing of the rest across the bottom, and lower the wire tray down, keeping the handles near the rim of the hole for easy retrieval. Add a bed of banana leaves to the chicken-wire tray before placing the wrapped pork shoulder onto its center. Add some more leaves to the top of the assembly, and then start replacing the rocks you took out around and on top of the pork, so that it’s getting heat from every direction. Then throw all the dirt back into the hole.

The timing will vary, depending on how many rocks you have in the pit, their size, and the ground in which you’re cooking. (Avoid doing this in claylike dirt, especially if it’s damp. It’ll be difficult to work with and could harden during cooking.) On my latest venture, I pulled a ten-and-a-half-pound pork shoulder out after six and a half hours. The results were marvelous: it was deeply and uniformly browned, impossibly tender but still sliceable, and, perhaps because its flavor had been reinforced by all of its trapped and steaming juices, it possessed an ineffable quality of being more than what it should have been. The rocks were still hot, meaning it could have gone longer. For some quantitative assurance, the pork temperature should read in the range of 170 or 180 degrees on a thermometer, or closer to 200 degrees for something that approximates pulled pork. But as it’s cooking, you just have to trust your intuition, which is part of the fun. The other part is calling your friends over and watching their faces as you pull their dinner out of the ground.

For a second, Outside+ member-only technique, please follow this link.

Source link