No products in the cart.

Outdoor Adventure

A Closer Look at the PR Feud Between Liberty Oilfield and The North Face

This article was first published by OutsideBusinessJournal.com. To get more of their premium content along with your Outside subscription, join Outside+.

Colorado native Chris Wright is an outdoor enthusiast who believes in buying premium apparel and equipment for his adventures near and far. He’s also an oil and gas executive who understands the critical role his industry plays in sourcing, producing, and transporting the gear that outdoor brands market and sell to consumers the world over.

So when Wright, the CEO of Denver-based Liberty Oilfield Services LLC, learned that outdoor industry stalwart The North Face wouldn’t make a co-branded jacket with one of Liberty’s competitors, Innovex, because it’s an oil and gas company, he was incredulous.

“I’d always been a pretty big fan of The North Face, and I proudly bought 2,000 North Face jackets for everyone in our company with Liberty and North Face logos on them,” Wright told Outside Business Journal. “So it was a slap in the face when they wouldn’t make jackets with Innovex. I thought of all these hard-working people in my company who proudly walk around with their North Face and Liberty jackets, and now they’re reading in the press that The North Face doesn’t want to associate with our industry?”

To protest this perceived slight, Liberty employees placed duct tape over The North Face logos on their co-branded jackets—but that was only the beginning. Wright and his team cooked up a bigger plan to point out what they called hypocrisy from The North Face by launching a tongue-in-cheek yet powerful marketing campaign.

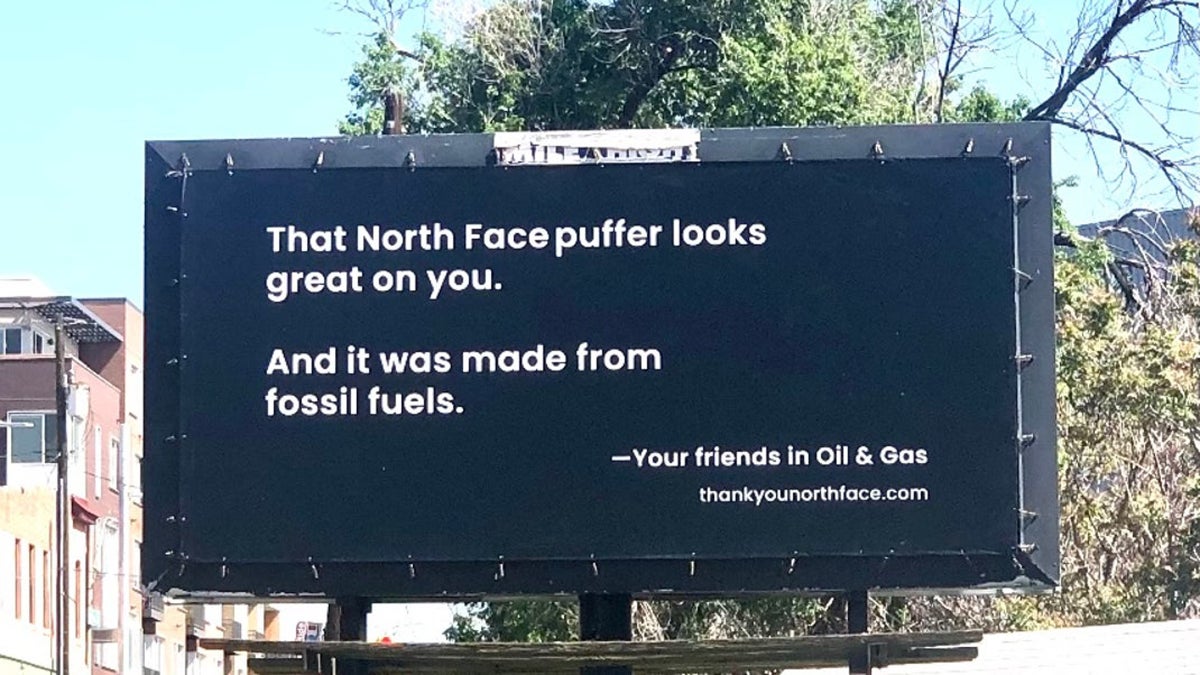

They commissioned seven billboards that read, “That North Face puffer looks great on you. And it was made from fossil fuels.”

Liberty placed the billboards in and around downtown Denver where The North Face and its parent company, VF Corporation, are headquartered. Wright also filmed a video for YouTube in which he didn’t call out The North Face but rather thanked the brand for making quality outdoor gear—with the help of the oil and gas industry, of course. Watch the video below.

The campaign went viral in early June and the national consumer press, along with some oil and gas trades, picked up the story. Wright said the response was mostly positive as colleagues and competitors—and even a few outdoor brands, he noted—cheered the massive amount of shade Liberty threw at The North Face. But Wright also said he wasn’t trying to “troll” the brand, as some headlines called it.

Instead, he saw this as a chance to educate outdoor consumers on a few key points—that oil and gas suppliers make jackets sturdier, tents lighter, and climbing equipment tougher; that outdoor brands should view the oil and gas industry as a partner, not a pariah; and that The North Face fracas was emblematic of a larger, longstanding misconception about oil and gas producers.

“I don’t want to be overly critical of The North Face,” Wright said. “I think they’re more a symptom of the problem than the cause. The North Face didn’t cause this problem. My single biggest concern is that this is a misunderstanding of energy, which is what makes the world go round. That’s always been the case, and I don’t fault people so much for it. But we have a dangerous combination today of people who are ignorant about energy but also passionate about oil and gas being evil.”

The North Face Responds

So that’s one side of the story. Whether Wright’s assertions about the oil and gas industry hold up under close inspection is grounds for (serious) debate, of course. Several passionate arguments have been made challenging Liberty’s provocative marketing campaign, including one from our sister publication, SKI magazine, that called Wright’s criticism of The North Face an “asinine talking point” intended as little more than a PR stunt.

The North Face, for its part, has remained reticent on the subject. Samantha Wannemacher, the brand’s senior manager of corporate communications, told OBJ that the company wouldn’t conduct interviews about the matter. She directed media inquiries to a page on The North Face’s website, where the company made a short statement regarding co-branded products.

“Letting another company put its logo on our products and essentially affiliating our brand with theirs isn’t a choice we take lightly, which is why these inquiries are thoughtfully considered with our brand DNA and long-standing outdoor values in mind,” the statement reads. “We manage co-branding requests on a case-by-case basis. There are times we choose not to sell product to certain organizations, from a variety of industries, with the intent of placing their logo next to ours. This includes companies in the oil and gas industry.”

Later in the statement, The North Face admitted that it does rely on oil and gas for sourcing, making, and distributing products. However, the company added, it is looking to lessen that reliance and hopes that oil and gas companies are also making their processes and practices more environmentally friendly.

“We fully acknowledge and recognize the integral role the global oil and gas industry plays in powering our business and our world,” The North Face wrote. “We are currently reliant on this industry for many of the products we make, fuel for when we travel, and for the energy we need to operate our business. We applaud any efforts currently being made within the oil and gas sector to pursue policies designed to reduce their carbon footprint and invest in clean energy technologies.”

The North Face then listed some of the improvements it’s made in reducing “environmental impacts to achieve the goals we’ve set for ourselves, all while managing our brand in ways we believe are the best for the long-term health of our business—even if our decisions are unpopular with some.”

‘It’s Complicated’

If the outdoor industry had a Facebook page and needed to define its relationship with oil and gas, “it’s complicated” would be the best option.

The makers of apparel and equipment rely on the industry for raw materials, production, and distribution—basically, everything that goes into the skis and sleeping bags, boats and bikes, hiking poles and hiking boots that outdoor enthusiasts need. Some companies have found ways to produce gear without oil and gas in the products (skis made of algae, for example), but they all need it to make their products and deliver them to consumers. Even producing recycled gear demands fossil fuels.

Still, reducing their environmental impact is what brands across the outdoor industry are striving toward, said Amy Horton, senior director of sustainable business innovation for Boulder, Colo.-based Outdoor Industry Association. Horton said that while outdoor brands—and indeed every business and individual—are reliant on oil and gas, the goal is to reduce that reliance.

“We all use energy to power our lives every day and to make outdoor products,” Horton told OBJ. “OIA takes a ‘reduce, remove, and advocate’ position.” That includes using different materials and moving away from fossil fuels, using alternative and renewable energies for their facilities such as solar-powered plants, and helping oil and gas communities transition to cleaner energy.

“We encourage brands to look at all the levers they have in their products and pursue the strategies that make the most sense for them,” Horton said. “That will help them meet their targets.”

She said there are opportunities for companies to make progress across all links of the supply chain, and OIA is helping lead that charge through the Climate Action Corps, which encourages companies that join “to commit to measure, plan, and reduce their greenhouse gas emissions and share their progress annually.”

“The Climate Action Corps is asking what are the opportunities to reduce our carbon footprints, and then we’re going to focus on those,” Horton said. “OIA is leading the way, but ultimately brands will need to implement these solutions. Thankfully, there are lots of drivers for doing that. I think our customers, our employees, and even our retailers, like REI, are expecting this of us.”

But as brands look for ways to support environmental causes, promote their sustainable efforts, and protect wild places from an industry that drills and excavates, conflict arises. Whatever side they take can put them in hot water with segments of people who buy their gear, noted Chris Harges, director of brand for Marmot.

“Brands are now part of the political ecosystem, whether they like it or not,” he told OBJ. “Our consumers have strong opinions, and they expect brands to align with those opinions. The difficulty for brands is that not all of our consumers have the same opinion. We find that on issues related to sustainability or diversity, we get blowback from both sides of the political spectrum. While we strive to do what we believe is right, just, and aligned with our brand purpose, we often find that comments on our social channels will split three ways: those who think we are on the right path, those who think we are not moving fast enough, and those who are offended by our stance.”

‘Get Woke, Go Broke’?

One brand that regularly sees its social and political stances go viral on social media and in the mainstream media is Patagonia. The company is renowned for its bold opinions on a variety of environmental and political issues.

A common refrain on social media is that if brands “get woke, they’ll go broke.” The thinking (up for plenty of debate) goes like this: If brands make their stances on political and cultural issues public, they’ll lose customers who disagree with those stances. Take a look at some of the comments on Wright’s YouTube video for proof.

Going broke hasn’t been the case with Patagonia, however, whose executives have publicly stated that revenues surge when the brand stands up for a cause. In 2018, then-CEO Rose Marcario staunchly defended the company’s campaign against the Trump administration’s attack on public lands.

More recently, in a May 9 article, “Patagonia shows corporate activism is simpler than it looks,” current CEO Ryan Gellert told the Los Angeles Times: “People often ask, ‘Are you a for-profit business or are you an NGO?’ And the answer in my mind is yes; I think we’re some weird mashup of those two things. What we really are is a for-profit business, and we use the business to try to influence larger, more systemic issues.”

Watch: Straight Talk with Ryan Gellert of Patagonia

Patagonia is winning with consumers’ hearts as well as their wallets. A recent poll from Axios ranking the reputations of American companies named Patagonia the most credible business in the U.S., based on scores in seven categories: affinity, ethics, growth, products/services, citizenship, vision, and culture.

How much, if at all, Liberty’s campaign impacts The North Face’s financial outlook remains to be seen. VF will report fiscal Q1 sales in July, but it is coming off an exceptionally strong quarter in which companywide revenue improved 22.8 percent to $2.6 billion.

One advantage for the parent company is that it boasts a massive collection of assets, including the “outdoor” portfolio of The North Face, Altra, Icebreaker, Smartwool, and Timberland, and the “active” portfolio of Eagle Creek (which VF is sunsetting), Eastpak, JanSport, and Vans.

That means VF can likely survive a hit to any single brand in a quarter. Can it withstand a negative PR campaign against one of its core brands? Probably. Especially given the reality that those who claim they’re going to boycott a brand over a political or social stance may not back it up anyway—or were never customers in the first place.

The Path Forward

Some of the sources we spoke to (both on and off the record) for this story, including Wright himself, suggested there is a path forward—a way for the outdoor and oil and gas industries to co-exist without the threat of canceling anyone. Even if brands don’t shout from rooftops that their products are made of oil and gas, some said, they shouldn’t disavow the industry if they don’t want to be called out for hypocrisy and alienate certain consumers. Instead brands should be upfront about the role that oil and gas play in this industry while continuing to push for carbon-neutral or carbon-positive products and processes. That, at least, is one school of thought.

“Probably the majority of [The North Face’s] customers have no idea that their jackets, their tents, all their gear are made out of oil and gas,” Wright said. “Their customers don’t know that plastic and polyester and polyvinyl and all these materials are oil and gas. I’d love it if The North Face just said, ‘All right, look, we’re going to be honest. Our products are made out of oil and gas, but we’re looking to be more efficient, so we’re going to reduce our reliance on your products.’ But they don’t. It’s like this dirty secret, but it shouldn’t be.”

On the other hand, a brand’s environmental ethos is often part of the reason it attracts fierce evangelists and lifelong customers. Companies that do take a strong stance should prepare for some backlash. That’s where a strong PR team and a firm messaging position come in. Each company has to assess its appetite for controversy.

“Finding the right balance is difficult,” said Marmot’s Harges. “But a solid understanding of your brand purpose should serve as a guide. Marmot’s brand purpose is based on building a community for everybody who enjoys outdoor sports. That goes all the way back to the founding of the brand. We’re going to pursue the initiatives that work towards building that community and making it as inclusive as it can possibly be. It’s hard to believe that there are consumers out there who are not aligned with that idea, but there will always be a few negative voices in the audience.”

Despite the apparent trolling of The North Face, Wright said he wants to move past this. He’d love for the outdoor industry to embrace its partnership with oil and gas, not disavow or disown it. At the end of the day, he said, he believes there’s more alignment here than some care to admit.

“We’re making raw-material products that keep getting better and, on a relative scale, cheaper,” Wright said. “Then, awesome designers at The North Face and Patagonia and Marmot are designing how best to use those materials to make stoves and tents and jackets. It’s a great partnership. That’s how I’m viewing it.”

Whether or not the outdoor industry takes that position seriously—and takes Wright at his word—remains to be seen.

Source link