No products in the cart.

Outdoor Adventure

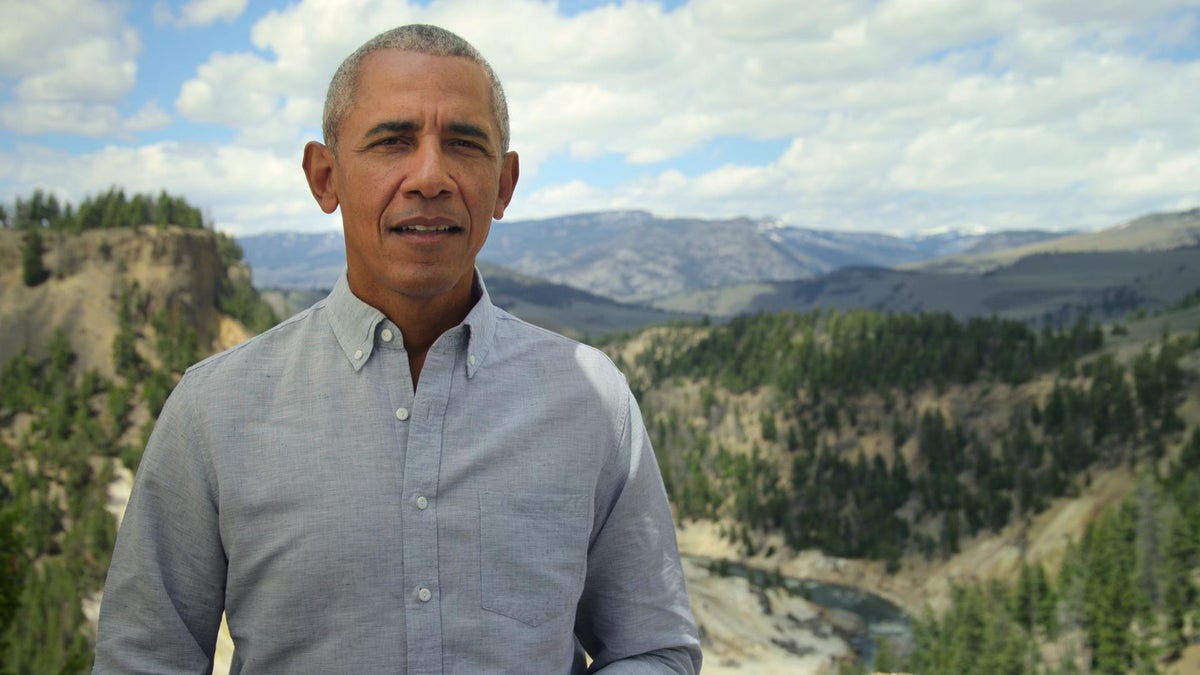

President Obama Is Narrating a Netflix Nature Series?

In 2018, former President Barack Obama sat down with David Letterman on the pilot of the comedian’s Netflix series My Next Guest Needs No Introduction. It was Obama’s first talk show interview since leaving office, and the most revealing insight into what Obama’s long post-presidency might look like–he was only 55 years old at the end of his second term–came when he remarked that his wife, Michelle, recognized the true power of the nation’s highest office before he did. Obama told Letterman, “Part of your ability to lead the country doesn’t have to do with legislation, doesn’t have to do with regulations—it has to do with shaping attitudes, shaping culture, increasing awareness.”

A few months later, Netflix announced it had signed a multiyear deal with the Obamas to create original content for the streaming service. Under the imprint Higher Ground Productions—seemingly a nod to Michelle Obama’s famous catchphrase “When they go low, we go high”—the former first couple has produced three children’s shows, the Oscar-winning documentary American Factory, the Peabody Award–winning film Crip Camp, and the Emmy-nominated documentary Becoming, based on the former first lady’s memoir.

Barack Obama’s latest Netflix venture is the five-part nature series Our Great National Parks, which came out earlier this month. It’s his first Netflix gig in front of the camera, stepping into a David Attenborough–esque role as narrator, highlighting protected lands around the world, from the snowcapped mountains of Chilean Patagonia to the species-rich waters of Monterey Bay in California. As an addition to the nature-doc genre, Our Great National Parks is fairly formulaic, but viewed as a piece of presidential branding that tells a certain story about environmental issues, it’s much more illuminating.

The Obamas aren’t the only former White House occupants to pivot to content creation. Hillary Clinton launched the podcast You and Me Both in 2020, the same year she and her daughter, Chelsea, founded HiddenLight Productions. Bill Clinton started his own podcast, Why Am I Telling You This?, early last year, and Mike Pence began hosting his podcast American Freedom a few months later. Most recently, Donald Trump rolled out the Twitter look-alike app Truth Social. With varying degrees of success, the projects that former politicians take on as private citizens are attempts to shape their legacies and speak to the causes they care about, says Joshua Scacco, a communications professor at the University of South Florida. “Political leaders have realized they actually do harness a lot of power in the attention economy. They’re late to the game in some ways, but they’re catching up very quickly.”

While Obama never mentions his time as president in Our Great National Parks, the series nevertheless leans into his story and legacy. Three episodes focus on national parks in places that Obama has a personal connection to: Hawaii, where he was born; Indonesia, where he spent some of his childhood; and Kenya, where his father lived. Promotional copy for Our Great National Parks emphasizes, “This isn’t out of left field: Obama protected more public lands and waters than any U.S. president.” The series, the news release says, is “as much a celebration of nature as it is a call to action.” In the opening shot of the first episode, Obama walks barefoot on the beach at Hanauma Bay Nature Preserve, in Hawaii, dressed casually in chinos and a linen shirt with rolled-up sleeves. “My love of the natural world began here,” he says. “I want to make sure that the world’s wild spaces are there for my kids and my grandkids.”

In the story Obama’s trying to tell, we are all equally culpable in, and equipped to solve, the world’s environmental crises. Between stunning scenes of lemurs jumping over limestone peaks and monarch butterflies taking flight, he stresses the importance of nature preserves and warns of the effects of climate change. But besides offering praise for some local efforts—landowners around Kenya’s Tsavo National Park expanding a conservation area, and community members removing plantations in Indonesia’s Gunung Leuser National Park, for example—Obama provides no specific solutions to our climate crisis, nor indictments of the corporations and governments most responsible. Even his new initiative accompanying the documentary, Wild for All, recommends anodyne actions like signing a nature petition or visiting a wildlife center. Increasing pollution and extreme weather, Obama says, are “the result of the choices we all make in our daily lives.” Never mind that just 100 companies account for 71 percent of global industrial greenhouse-gas emissions or that the U.S. is the biggest carbon polluter in history.

He also avoids wading into the complicated history of U.S. national parks, and instead uncritically celebrates them, like generations of American statesmen have, as our best idea. “In 1872, Yellowstone, in the western United States, became the first national park in the world,” Obama says as the camera pans over its spectacular hot springs and mountain ranges. “One of America’s greatest ideas, established for the benefit and enjoyment of the people.” What he chooses not to mention is that to create Yellowstone, the U.S. violently forced out the Shoshone, Bannock, Crow, and Nez Perce tribal nations, as well as numerous others who called the area home before white settlers arrived.

“Many of these landscapes were very carefully and sustainably managed for centuries, if not millennia,” Ryan Emanuel, an environmental-science professor at Duke University and enrolled member of the Lumbee Tribe, says. “The U.S. put up rules and regulations that prevented people from carrying out their ancestral practices on these lands, and to not acknowledge that is a major oversight.”

“It’s not really a historical series,” said executive producer James Honeyborne, who also produced the BBC Natural History Unit’s Blue Planet II and Patagonia: Earth’s Secret Paradise, when asked why Our Great National Parks didn’t include these accounts.“It’s really a more forward-facing series, looking at the importance of wilderness to us now and to the relationship humans have with it going forward.”

The series’ most politically charged moments arrive at the end, when Obama urges us to “demand” to protect public lands, to “campaign” for more, to “push” for better in our own communities. But he doesn’t name-check anyone in power for us to demand anything from. His most concrete proposal? “Vote like the planet depends on it.” To be sure, there’s no disputing that a meaningful fight against climate change requires all of us. But the message rings hollow coming from the former occupant of the most powerful office in the world—even if that former officeholder did enact progressive climate policy. If Obama has a political message in Our Great National Parks, it’s to affirm American mythology about personal responsibility, the altruism of conservation, and our best idea.

In the middle of the series’ first episode, Obama narrates footage of a three-fingered sloth basking in the sun, as an acoustic guitar gently strums in the background. He tells viewers about fungus in the sloth’s fur that has the potential to fight cancer, malaria, and antibiotic-resistant superbugs. “If we can protect him and his rainforest, this sleepy sloth might just save us all,” Obama says. It’s a line brimming with hope, and in that sense, it’s very on-brand.

Source link