No products in the cart.

Outdoor Adventure

New Study Finds Meditation Offers Significant Endurance Benefits

New perk: Easily find new routes and hidden gems, upcoming running events, and more near you. Your weekly Local Running Newsletter has everything you need to lace up!

Subscribe today →.

Back in 2018, I wrote an article about some new research showing that mindfulness training could improve mental and physical performance in elite athletes. It was a heady time for mindfulness, and my article was just one in a frothing sea of hype about the practice. The hype has quieted down since then—interest has dropped by about a third since 2020, according to Google Trends—but the evidence that mindfulness and other forms of meditation have real benefits continues to quietly accumulate.

The latest example: a new study in the Journal of Sports Sciences from a team of researchers at National Taiwan Normal University led by Yu-Kai Chang. Chang and his colleagues compared two groups of athletes, one of which had experience with meditation, and found striking differences in how they were able to handle mental fatigue and maintain focus during endurance exercise.

What the Study Tested

The subjects in the study—24 meditators and 25 non-meditators—were all serious athletes in a mix of sports including track and field, judo, and wrestling. They had an average age of around 20, and trained on average for 16 hours a week. Three quarters of them were male, a quarter female. They had similar performance in a cognitive test that involved remembering a series of digits.

In other words, the two groups were very well matched in all respects except one: the meditators reported spending an average of 41.7 minutes per week meditating, and had been doing it at least once a week for a year or more. To be eligible for the study, their meditation had to fall into one of two categories: focused attention (paying continuous attention to a specific object) or open monitoring (focusing on whatever arises in the present moment). The meditators, as you’d expect, also scored slightly higher on a questionnaire that assessed their typical level of mindfulness in daily life.

To find out if there was a link between meditation and endurance performance, the study protocol involved doing a mentally fatiguing computing task (more on that below), then a cognitive task that assessed their “inhibitory control,” then a progressive treadmill test to exhaustion. Inhibitory control is what it takes to stay focused, tune out distractions, and resist impulses that interfere with your goals. In some sense, the mental side of athletic endurance is one big test of inhibitory control—so you can think of the study protocol as a computer-based test of inhibitory control followed by a treadmill-based test of the same thing.

The Role of Mental Fatigue

At the start of a marathon, you may be hyper-motivated to run yourself into the ground. By mile 20, your body is begging for mercy—and, more often than not, your mind is no longer as laser-focused on squeezing out whatever energy you have left. It’s hard to keep holding your finger to the flame; it takes a lot of concentration, and that concentration tends to wane over time. In recent years, sports scientists have been trying to unravel the exact causes of this mental fatigue—one theory is that it’s related to the build-up of a brain chemical called adenosine—and looking for ways of counteracting it.

In this study, the researchers used a task called the Stroop Test to ramp up the mental fatigue in their subjects. A color word flashes on the screen, either RED, GREEN, BLUE, or YELLOW. The letters are displayed in one of those colors, and you have to quickly press a button corresponding to the color of the letters. The catch is that the color of the letters doesn’t match the word (RED might appear in green letters, for example). You have to inhibit your automatic response to the semantic meaning of the word in order to respond only to the display color. This is mentally taxing, and after half an hour has been shown to reduce both mental and physical performance.

In the control condition, the subjects did the same Stroop Test for the same half-hour, but with the colors and words matching so that it didn’t tax their response inhibition. There’s some previous research showing that experienced meditators have better response inhibition, so the researchers hypothesized that the meditation group would perform better after the mentally fatiguing version of the Stroop Test.

Meditation and Endurance Performance

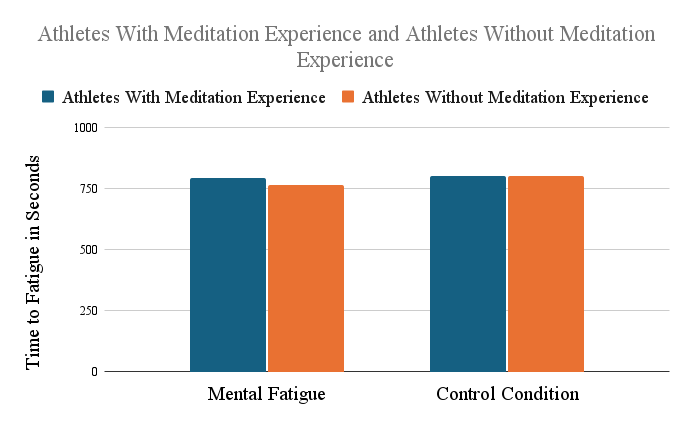

The results were more or less what the researchers expected. For athletes, the key outcome was how they did on the time-to-exhaustion treadmill test. Here’s how meditation affected endurance performance for the athletes with meditation experience (AME) and athletes without meditation experience (AWME):

In the control condition (right), which was preceded by the non-fatiguing Stroop Test, the two groups were roughly equal. In the mental fatigue condition (left), the meditators produced almost the same performance, while the non-meditators gave up 4 percent earlier. There were similar results in the computer test that assessed inhibitory control: the non-meditators got worse when they were mentally fatigued, and the meditators didn’t.

There are two ways to think about these results for meditation and endurance performance. One is that the meditators, with their superior response inhibition, didn’t find the Stroop Test mentally fatiguing, so their subsequent performance was unaffected. The other is that the meditators did get mentally fatigued, but their superior response inhibition enabled them to shake it off and stay on the treadmill. If you look at their subjective ratings of mental fatigue at various stages of the protocol, it looks like there’s a bit of both: the meditators had lower but non-zero levels of mental fatigue, and they didn’t let that mental fatigue affect them on the treadmill.

One of my questions about the meditation-for-sport research has always been whether meditation helps more than regular training already does. Sure, you can improve your response inhibition by sitting on a mat. But if you spend many hours a week training hard and pushing your limits, isn’t it possible that you’ve already maxed out your response inhibition? Doesn’t marathon training count as meditation? It’s a tricky question, but if athletes who are already training 16 hours a week get a measurable benefit from an extra 40 minutes of meditation, that suggests there’s something more to it.

For more Sweat Science, join me on Threads and Facebook, sign up for the email newsletter, and check out my book Endure: Mind, Body, and the Curiously Elastic Limits of Human Performance.

Source link