No products in the cart.

Outdoor Adventure

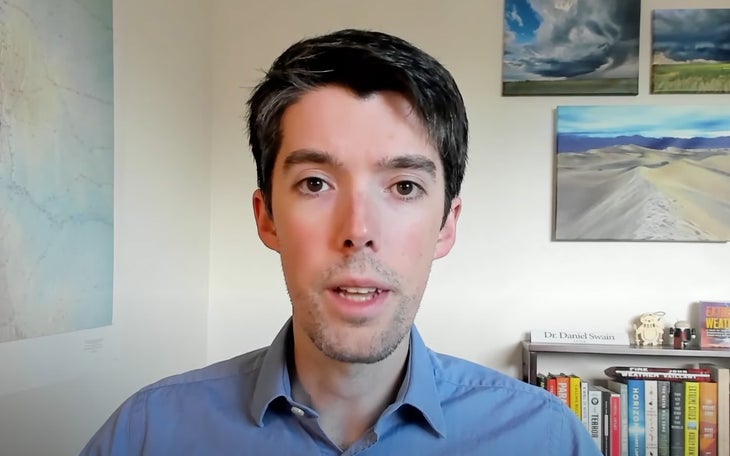

A Climate Scientist Explains the Los Angeles Fires

New perk: Easily find new routes and hidden gems, upcoming running events, and more near you. Your weekly Local Running Newsletter has everything you need to lace up!

Subscribe today.

This past Saturday, January 4, Daniel Swain, a climate scientist for the University of California Los Angeles, published a lengthy post on his blog, WeatherWest.com. In the post, Swain warned of an “extreme offshore wind and fire-weather event” in Southern California in the coming days.

Two days later, Swain posted a YouTube video where he again sounded alarm bells for Los Angeles. “The quite serious extreme wind and fire-weather threat in Southern California—it is going to affect millions of people and potentially cause some real damage and really ramp up the threat of destructive wildfire,” Swain said. A handful of news outlets published Swain’s comments.

On Tuesday, January 7, wildfires erupted across Southern California, with the largest blaze igniting in the Pacific Palisades region of Santa Monica. Whipped by extremely high winds, the inferno enveloped thousands of homes and businesses and killed at least five people. Hundreds of thousands of residents evacuated as the blazes roared through neighborhoods across Southern California, including Altadena, Pasadena, and Pacific Palisades. As of the publishing of this story, the fires were zero percent contained.

We caught up with Swain to talk about the conditions that led him to post his warnings.

What dynamics led you to predict an extreme fire event in Southern California this week?

SWAIN: This was an extraordinarily well-predicted extreme weather and fire risk event, and I wasn’t the only person who saw it coming. The national weather service gave strong messaging—Red Flag, high-wind watch. These are tiers of warnings that are rarely issued. We saw the extreme winds coming to Los Angeles perhaps a week or so out. But more importantly, we knew that the dry conditions across Southern California were exceptional. That has been cumulative, over months. So, if a big bad wind event came along before the first rains came, we knew that the fire danger would be bad.

But going further back in time, the past two years were very wet in Southern California—historically wet in some areas. People celebrated that the drought was over, and it was. We aren’t seeing long-term drought right now, but we’re seeing something different, which is called hydroclimate whiplash. That’s where you go from extreme wet to extreme dry. So, we had extremely wet weather and then the driest six-to-nine month stretch ever observed. This sequence matters in Southern California, because what you see burning isn’t mature forest but rather grass and brush, which grows in periods of high moisture.

What role did climate play in these fires?

There are two climate connections. In a warming climate we’re seeing wetter wet periods and drier dry periods, but it’s warmer all of the time. That’s a dangerous sequence. You have these increasingly wide swings between extreme wet and extreme dry, which leads to the abundant growth of grass, brush, and vegetation that burns easily. We also see hotter summers and drier falls and early winter, which extends fire season into the winter. And as you extend the fire season, it starts to overlap with the season of strong offshore winds. Having high winds in January isn’t too unusual. But having an abundance of vegetation as dry as it is right now is not typical. That’s the other dangerous component.

We actually saw this danger coming nine months out. Of course you can’t pinpoint the exact dates. But we saw that the summer was the hottest on record across Southern California, followed by a heat wave in the fall that baked and dried out the vegetation. And it hasn’t rained. Each piece of this contributed in a way that makes ecological and meteorological sense.

What similarities do you see between this and the Marshall Fire in Boulder County, Colorado, back in December, 2021?

I see some parallels. It was a bone-dry fall and start to winter in Colorado when the Marhsall Fire sparked. Of course dry winters are more typical in Front Range Colorado than they are in coastal California. But in 2021 in Colorado we hadn’t seen snow by late December, and then we had an extreme downslope wind storm. The winds were actually more extreme during the Marshall Fire.

A lot has been written about the fire danger as the wildland-urban interface continues to expand.

The Marshall Fire was definitely a mixed wildland/urban fire where the fire went from open spaces and rural areas into neighborhoods, where it then burned structure to structure, block by block. The Southern California fires are more like urban fires than a true wildland fire. They started close to densely populated areas and the moved quickly into town centers and more neighborhoods. This wasn’t a true wildland-urban interface fire. In some of these city areas it’s just spreading from the house, to the PetCo, to the mall, to the gas station.

When winds are that extreme there doesn’t need to be an abundance of vegetation for it to spread. But like the Marshall Fire, we are seeing it spread up creek corridors and parks like a candle wick. The vegetation found in urban parks, open space, and even medians is still fuel, even if it gets irrigated.

If scientists predicted fires, why have they been so devastating?

It’s hard for even me to fathom, but these fires would have been worse had we not had the predictions. The warnings led to preemptive positioning of aircraft and fire crews. Had the predictions not been as good, you would have seen fewer firefighters and crews in place in those first hours. And it was the work that people did during those first few hours that probably saved hundreds of lives. There could have been an incredible loss of life in this scenario, and we came close to it in Pacific Palisades. California has a veritable army of firefighters in Los Angeles, the LA City and local departments, CAL Fire, Cal Office of Emergency Services. But yes, this is still what we see—under conditions this powerful, this kind of destruction can still happen. I don’t see this as a failure of firefighting. I see it as a tragic lesson in the limits of what firefighting can achieve under conditions that are this extreme.

This interview was edited for space and clarity.

Organizations Accepting Donations to Help Those Affected by the Fires

Source link