No products in the cart.

Outdoor Adventure

Are Yeti Products Worth the Money?

The first Gear Guy video I produced for Outside in 2013 is, to this day, my most ambitious. It was also the scariest thing I have done while testing gear. I have always taken pride in testing gear rigorously enough to put myself in danger at times. On other assignments for this publication, I have ice climbed on thousands of feet of exposure on mixed routes in Chamonix, shivered next to a feeble fire in shorts through a night when a freak snowstorm locked my group in a deep river canyon in the Sierra, and triggered a loose wet slide avalanche that I outskied on Mt. McLoughlin. Those moments stick out as scary, but they pale in comparison to the cold, butt-puckering, fear I felt while I faced the camera and delivered the lines “…and punished it” while my dear friend Saylor fell a 50-foot tree onto a Yeti Tundra 110 cooler ($550) behind me.

If you buy through our links, we may earn an affiliate commission. This supports our mission to get more people active and outside. Learn more.

We dropped the dead tree legally and in an environmentally sound manner, but I still regret the decision because it was just so fucking dangerous. I could have been crushed if Saylor messed up his chainsaw work by an inch. I wanted to pretend it was no big deal, so I didn’t look back at the tree while speaking into the camera. Our camera operator, Pat, told me he would yell “Bail!” if the tree looked like it was coming our way. When I heard the crack that let me know the tree was on its way down, life moved in slow motion. I could see the shotgun mic on Pat’s camera jiggling from his shaky nerves.

The tree hit its mark beautifully and the cooler beneath it survived the ridiculously massive impact. The middle of the lid was a little warped from the hit, but the hinges still worked and the body held strong. My buddy Saylor used boiling water and a rubber mallet to restore the cooler to near-new—and used it on river trips for half a decade after the test. I haven’t been able to top that level of gear testing since then (nor would I want to now, as a forty-one-year-old father).

Professionally testing outdoor gear for the ten-plus years since then has been a dream job. Also: professionally testing outdoor gear limits the number of topics outdoorsy acquaintances want to talk to me about. I have lied about my job at parties because I knew that if I mentioned what I did for work, the night would descend into backcountry ski touring binding talk and I would miss an opportunity to connect in any real way. I have answered thousands of questions about gear over the last decade.

But the one question I have been asked the most, by far, is: “Is the Yeti [insert product] worth the money?” I have been texted the question so many times that I had to type an automatic answer on my Notes app about roto-molding and insulation to be ready to copy and paste.

So, Are Yeti Products Worth the Money?

Yes. If you are here because of the headline, my TLDR is Yes. Yeti products are worth their high price tag. The rest of this article is more of an answer to why I think the super-premium, ridiculously overbuilt products are worth the money. That “why” isn’t simple.

First, I want to address the large mythical snow monster in the room: I have not paid for any of the Yeti products I have tested over the years. I have also held on to many of the ones I did not destroy while testing and still use them to this day. Many would say that the fact that I haven’t paid for these products would discredit my belief that the high price tag is warranted.

I have never, however, paid out of my pocket for any products I have tested for Outside (I would hemorrhage money if that were the case). The fact that I have tested them all for free gives me freedom to address the price based solely on the merits of the product. The fact that I have not paid for the products does make the conversation about price more philosophical since my own bucks aren’t in the game.

Yeti Products I’ve Tested

After a decade of dedicating my life and career to testing gear, I have gone the deepest on Yeti products, investing hundreds of hours to test dozens of products—and opining on their value. If you have not been closely following my column for Outside (don’t worry, my parents still tell their friends I work for Outdoor Magazine) here is a list of 15 times I weighed in on whether Yeti products are worth the price, and my verdict:

As you can see, the overall result leans pretty heavily towards yes, the two exceptions being the V Series cooler and the Hondo camp chair. But to be fair, the V Series cooler got a rough treatment. And while I was diplomatic about my assessment of the original Hondo, I could have been quoted at the time saying, off the record, “Only an asshole would buy themselves a $300 camp chair and watch their family sit in cheap ones, or pony up $1,200 for camp chairs for everyone.”

Since Yeti products test so well, it’s tempting to want to jump to a simple answer to the “why” question. If the end product is usually better than its competitors, it should be worth more. While that could offer a clean answer for individual products (particularly when comparing their first-generation Tundras to just about any other cooler on the market) it isn’t a satisfying answer when you look at Yeti as a company that posted 68 million dollars in sales internationally in Q3 of 2023 and now makes dozens of products beyond just coolers. I feel like completely focusing on individual performance to gauge value would demand a value call on each of the dozens of products they offer. But, before I take you all too deeply into those weeds, let’s take a quick refresh on the Yeti brand as a cultural phenomenon.

Behind the Brand

Brothers Roy and Ryan Seiders founded Yeti in 2006. The brothers were anglers and hunters based out of Driftwood, Texas, and their father, Roger, had seen success inventing super durable, high-performance, two-part epoxy fishing rods that sold at a premium price point. Because Roy was initially in the boat business, he wanted to make a super durable cooler that could also serve as a casting platform—something that would be virtually indestructible and irreplaceable. To achieve that goal, the brothers eventually landed on using rotational molding on the exterior of the coolers—the same technology that made whitewater kayaks exponentially stronger in the 90s—and jamming them full of a shit ton of insulation. The result was insanely durable and lightyears better than most of its competition. It was also way more expensive.

I brought up covering Yeti coolers in an editorial meeting in 2011 while I was a junior member of the staff at Outside. My pitch was clumsy and utilized my signature brand of rapid-fire, sweaty upper-lipped excitement—and I got crickets. I remember one editor, who happened to be one of my idols, looked down and shook his head in painfully visible disappointment. At the time, they were just coolers. Or were they?

Whether or not people asked for a $400 cooler, they have proven willing to pay for one in the past 14 years. I feel personally vindicated by Yeti’s bonkers success. In 2023, Yeti launched 15 new products. Their investor report for Q3 expected that for the 2023 year, they would have, “Capital expenditures of approximately $55 million (versus the previous outlook of $60 million) primarily to support investments in technology and new product innovation and launches.” Yeti now has dozens of communities of superfans ranging from Grand Canyon raft guides to octogenarian golfers. The company’s main business campus takes up 175,000 square feet. In other words, Yeti is massive.

Superior quality is a huge part of the story of Yeti’s success. I don’t think it is the entire story, but it most certainly is the foundation on which this juggernaut was built. I had heard of a low-key secret testing facility that Yeti had built to stress test their products somewhere in the mid-aughts and had pitched touring it for years. Last fall I had an opportunity to go see it and judge for myself how much effort they put into making sure their products could withstand abuse.

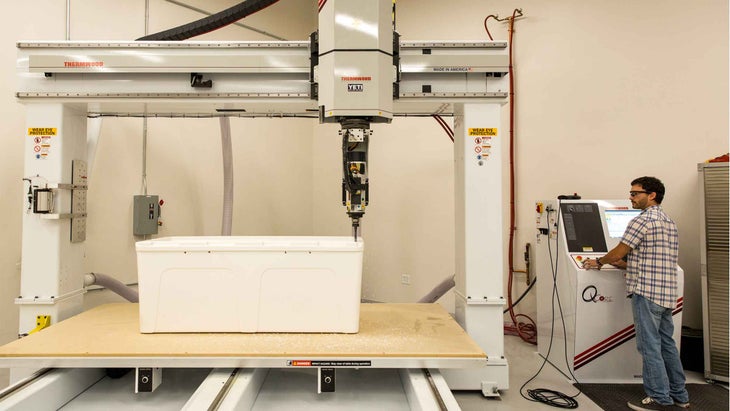

Their Innovation Center is an unmarked warehouse attached to office space, part of a sea of barely distinguishable buildings outside of Austin, Texas. When I entered, I was greeted with the noises of Yeti products getting their asses lightly and repetitively kicked everywhere. The first noise I heard was a Roadie Haul handle being extended and dropped by a robotic hand named Tripp every ten seconds. Tripp is one of the three UR5 Robotic arms that are in near constant use and are named for the heroic interns of yore (in this case: Tripp Arnold) who were employed to hand zip the original Hopper Soft Coolers 2,500 times, keeping track with a baseball clicker.

Throughout my two-hour tour of the facility, I saw dozens of machines that gave me more existential fear about robots replacing my job as a gear reviewer than any AI writing software has. There was a machine that dropped coolers from very precise heights over and over again. A robot that opens and closes four cooler lids at a time. A carousel that took rollie coolers on a circular course over obstacles like slatted decking and climbing holds before giving the wheels a stamp of approval. All told, there are 21,120 square feet devoted to testing Yeti’s vast range of products.

I have toured factories before—I’ve watched Keen employees carefully place soles on work boots and the folks at Benchmade expertly craft kitchen knives in state-of-the-art facilities here in the US. I have never seen anything close to this type of rigor on the industrial testing side, though. This whole space, the size of many factories, was devoted solely to testing and prototyping the gear. It was truly incredible and I desperately wanted its awe-inspiring magnitude to directly assign value to the Yeti products I have spent so much time testing.

In service of that goal, I badgered Matt Bryson, Senior Manager of Innovation and Validation Engineering at Yeti, for superlatives throughout the tour. “What’s the most weight you have placed on a product?” “Are there any products that took an incredible beating but failed at the last second?” “What is the craziest test you have performed on a product?” His answers were both incredibly smart and very unsatisfying in the way only a hyper-intelligent corporate product specialist can deliver.

“You don’t know what somebody is going to do with a product. It could be wild, something that you never even thought of. We have to prepare for anything. Since you don’t know everything someone can do, we typically over-index on everything,” Bryson said. “You can break anything. There is a point we call something abuse. You can’t set a cooler on fire and expect it to still work. We balance that fine line between heavy use and abuse really well.”

For the record, I think that is a fabulously smart answer. But it wasn’t enough to satisfy my obsession. I was begging him to give me a quote that would not only answer the “why” for this article, but for me, personally, as well. Honestly, I wanted the onus to be on him to assign value to this iconic outdoor gear category.

I was asking for more than manufactured tests could deliver. I was asking not just for impressive proof of the Yeti products’ performance and durability, but a statement that would sum up their significance in people’s lives. Honestly, though, a real-world scenario months before my visit had given me the answer. A solid cooler did benefit my life in ways that actually matter.

The Impact of a Well-Built Product

During a decade of testing, I have tested the crap out of Yeti products I have written about. I have thrown them from cliff tops, drug them behind moving vehicles (please note the plural), and filled one with hundreds of pounds of a fabrication shop’s debris and dropped it from a fully extended forklift. I have burned through at least six kitchen thermometers and hundreds of pounds of ice performing backyard thermoregulation tests.

While I took pride in the rigor of these contrived tests, it had been years since I depended on a cooler to show up for me performance-wise. Due to my life as a dad and waning desire to take risks, it had been a while since I had a real-world stress test scenario. Until last summer.

Last August, my then five-year-old daughter Josie and I found ourselves lightly stranded on the far northern California coast when wildfires shut down the highway that is the most direct arterial from the beach to our home. The town adjacent to our campsite, Crescent City, lost power for over a week. I heard reports from town asking people to stay out to keep the scarce resources open for firefighters.

I had a special week planned with my kiddo, however, so I checked in with the camp host to make sure that we weren’t taxing community resources if we kept to our site and the beach, and decided to wait until we ran out of ice or the road opened back up to head home. To be clear, this was not a real emergency—we could have driven the ten-hour drive home on the detour routes. The length of our trip, though, depended on the performance of our cooler.

Yeti Roadie 48 Wheeled Cooler

$400 at Yeti $400 at Dick’s Sporting Goods

We had brought two coolers, an ORCA 40 cooler ($325) and a Yeti Roadie 48 Wheeled cooler ($400). Both coolers had an even distribution of food, root beers, and La Croix’s, and each held a block of ice tucked into their right corner. I used the ice-maintenance tools honed over 20 years of multi-day rafting trips (basically, keep the fucking cooler shut!) to maximize our ice use, and we went about our solitary business.

It became clear on day two that the Yeti Roadie was doing its job better. I began moving prize cooler items—the block of Tillamook Cheddar, ravioli, Kerry Gold butter—over to the Roadie to hedge my bets against losing them. Every morning, Josie and I would eat the highly processed donuts in our sleeping bags (I called it her raft guide training), walk outside, take a super quick peek at our ice situation, and then make the call if we would take the long route (lengthened by about five hours from shut down roads) home or stay and surf for another day.

That trip was the most magical one of my year. I kept my phone charged using a solar panel and bank and we checked in with my wife in the mornings and evenings. Otherwise, it was just Josie and me. I talked and played with my five-year-old in the sun for hours with zero distractions. One day we played on the beach for nine hours and saw three other humans and two dogs. Another day, we didn’t leave a 200-foot radius and remained completely entertained with conversation, art projects, and learning tricks on her new bike. I spent as many uninterrupted and fully present minutes with her during that trip as I normally would in weeks—maybe even months.

Every morning I would silently pray that we’d still have ice in the coolers. By day five, the ORCA’s ice disappeared. On day seven the Yeti cooler still had a baseball-sized chunk in it. Josie and I could have easily stuck it out for two or three more days if we didn’t get called back home by a surprise visit from relatives.

I arrived at my parents’ house in Ashland utterly exhausted, with a truck bed full of camping supplies and a spectacularly dirty and happy five-year-old. I gave the dinner party a light recounting of the previous week’s challenges—an adventure that was really just an inconvenience mitigated by good gear. Somewhere in the middle of my story, Uncle Bob made eye contact with me over his slice of pepperoni pizza, and I saw it coming.

“I’ve gotta ask, Joe. Are those Yeti coolers worth the money?”

I invited Josie to sit in my lap and looked down at our dirty feet.

“Yes, Bob,” I replied. “Yes, they are.”

Source link