No products in the cart.

Outdoor Adventure

Brendan Leonard’s ‘Ultra-Something’ Explores Endurance

My new book, Ultra-Something, explores humans’ weird proclivity for endurance, and how we express it—including, but not limited to distance running, factory work, benign masochism, improv comedy, and rooting for football teams that will never win a championship. I ran thousands of miles and explored dozens of rabbit holes of research, athletics, and storytelling, then built it into a narrative, with more than 90 illustrations I drew. The final product is a 285-page book and it’s out now. (Buy it at Bookshop here, or at Amazon in paperback here, and on Kindle here.)

Here’s the book trailer:

The below is excerpted from the book’s prologue.

At the finish line of the 2015 Western States Endurance Run, arguably the most famous and most prestigious American ultramarathon, the crowd suddenly became energized. A runner was coming, entering the Placer High School track, where the 100-mile race ends after winding up and over California’s Sierra Nevada mountains from Olympic Valley Ski Resort.

Spectators cheered, clapped, and frantically rang cowbells, as the runner, Gunhild Swanson, rounded the track. A group of runners who had joined her peeled off at the start of the straightaway, clearing the way for her finish. The sides of the track were lined with people anxiously yelling “Come on, come on!” and other words of encouragement which sounded more like worried hope. More spectators ran across the infield, and a few paralleled her on the other side of the barrier fence set up on the track. Dozens of cameras and phones recorded her as she chugged toward the white finish arch, her strides shortened by 99-plus miles of mountain running and hiking over the previous day and a half. As she crossed the timing mat at the finish, the crowd erupted, hundreds of arms popping up into the air in a coordinated burst of emotion. Three feet past the finish line, the runner bent at the waist, hands on her knees, exhausted but grateful to be finished. Online videos of this minute of running would be watched hundreds of thousands of times.

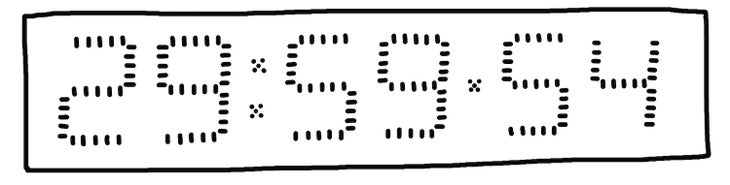

Gunhild Swanson had finished dead last, 254th out of 254 runners. When she crossed the finish line on the track, the clock above her head read:

She had beaten the final 30-hour cutoff time by six seconds.

When that year’s winners, Rob Krar and Magdalena Boulet, crossed the same finish line hours earlier, in 14:48:59 and 19:05:21, respectively, the scene was almost serene in comparison: some applause, some cheering, but with the overall energy and volume turned down.

The climax of Sylvester Stallone’s 1976 movie Rocky, when boxer Rocky Balboa finally squares off with the defending champion, Apollo Creed, only lasts about nine minutes, but might be the most famous boxing match in film history.

Apollo, who had been scheduled to defend his title against a boxer who was injured, needs to find a new opponent, and decides to put on a show: As the original fight was scheduled to take place during America’s bicentennial year in 1976 in Philadelphia, Apollo says he’ll fight an up-and-coming boxer. Rocky Balboa, a Philly club fighter with more heart than skill, is chosen.

When the fight begins, everyone, including Rocky and Apollo, is surprised that Rocky actually lasts more than a few rounds, even landing some good punches, and as the fight drags on, ends up making it longer in the ring than any other boxer has against Apollo.

After Apollo knocks Rocky down during the 14th round and he battles to pull himself back up, the camera cuts to two people who we believe have much better judgment as far as Rocky’s well-being: First, the trainer, Mick, who growls from just outside the ropes to Rocky, “Down. Stay down.” Then, Rocky’s girlfriend Adrian, who has just entered the arena to see Rocky at his worst, writhing in pain on the canvas. She looks away.

Rocky staggers in his corner like a drunken man trying to get back up on a barstool. Apollo stands in his corner with both arms raised.

Rocky gets up at the count of nine. Apollo drops his arms and his jaw in disbelief. Just before the bell, Rocky lands a shot to Apollo’s ribs.

When both fighters are in their corners, Apollo’s trainer says to him, “You’re bleeding inside, Champ. I’m gonna stop the fight.”

Apollo replies, “You ain’t stopping nothing, man.”

Rocky’s team cuts the swollen skin around his eye so he can see again, and Rocky stands up, saying to Mick, “You stop this fight, I’ll kill you.”

The two haggard fighters trade punches throughout the 15th and final round, mumbling promises to each other that there will be no re-match, and the bell rings, both men barely upright, but having survived. A bloodied Rocky calls out for Adrian, who finds her way to the ring, where she and Rocky profess their love for each other.

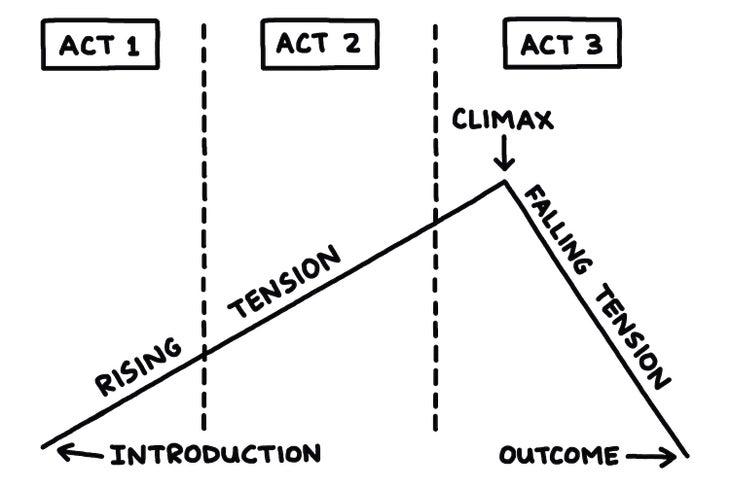

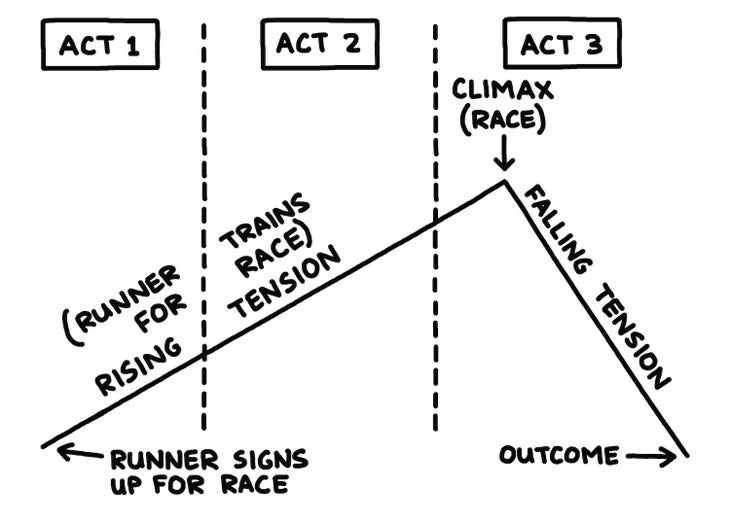

In the 1979 book, Screenplay: The Foundations of Screenwriting, Syd Field laid out what would come to be known as “Field’s Paradigm,” or the Three-Act Structure. Every screenplay, or actually, the story that forms a screenplay, Field argued, has three acts: set-up, confrontation, and resolution. The three-act structure is often drawn as a diagram, in various levels of complexity. A simple version might look like this:

Rocky went on to be a surprise box office success, and was nominated for nine Academy Awards, winning three, including Best Picture. The film spawned eight sequels over the next four and a half decades.

One scene in the original film, in which Rocky goes on a training run and ends by sprinting up the steps at the Philadelphia Museum of Art, became famous, inspiring tourists to run up the stairs, and prompting tributes and parodies of the scene in other films and TV shows. The 72 steps themselves became known colloquially as the “Rocky Steps,” and before the premiere of Rocky III, Stallone commissioned an eight-and-a-half-foot statue of Rocky to be built and placed at the top of the steps. Philadelphia City Commerce Director Dick Doran welcomed the statue and said Stallone had done more for Philadelphia’s image “than anyone since Ben Franklin.”

Rocky Balboa did not win the fight in Rocky. As the closing theme music builds, the ring announcer calls the fight “the greatest exhibition of guts and stamina in the history of the ring,” and then announces the split decision in favor of Apollo Creed.

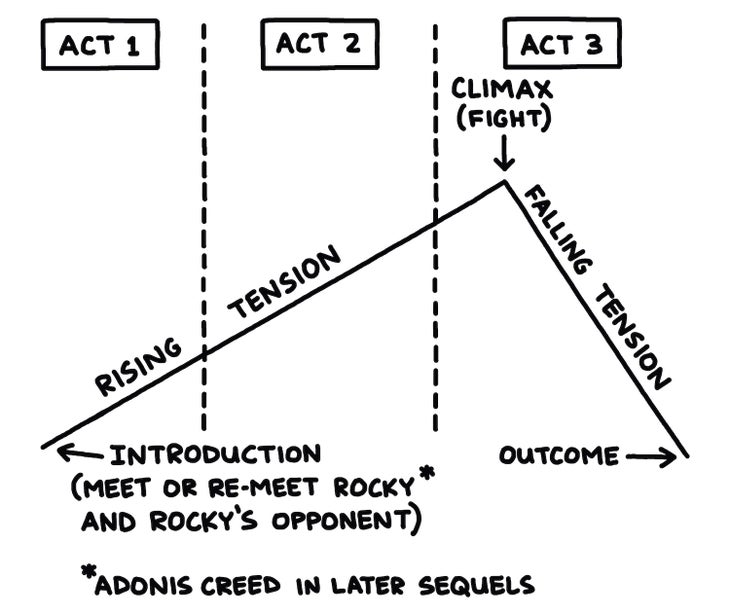

The plot of Rocky, as well as the plots of all eight sequels, per the three-act structure, might look like this:

At almost any marathon race in the United States, there is a solid chance you will hear, played on a sound system near the starting line, or on a spectator’s stereo along the race route, one of two songs, if not both: The song “Gonna Fly Now,” also known as “Theme from Rocky” (a version of which appears in the first five Rocky movies), and the Survivor song “Eye of the Tiger,” commissioned by Sylvester Stallone for Rocky III.

Every year around the world, about 1.1 million people run a marathon, an organized race that’s 26.2 miles, or 42.195 kilometers. The story of why we do this dates back to 490 BC: During the first Persian invasion of Greece, a heavily outmanned Athenian army defeated the Persian forces in battle near the town of Marathon, Greece. A herald named Pheidippides was chosen to deliver the news of the victory to Athens. He ran the entire distance of 26.2 miles/42.195 kilometers, addressed the magistrates in session saying something like, “Joy to you, we’ve won!” and then died on the spot.

The Greeks also created the tradition of the Olympic Games, held every four years, or each Olympiad, from 776 BC to 393 AD. The ancient Olympic Games never had a marathon race—the “long-distance race,” or dolichos, introduced in the 15th Olympiad, was somewhere between four and nine kilometers (approximately 2.5 to 5.5 miles). The last recorded ancient Olympic Games were held in 393 A.D., after which they took a 1500-year hiatus.

When the Olympic Games were revived in 1896 in Athens, the first marathon race was held, celebrating Pheidippides’s legendary (and fatal) run from Marathon to Athens. A few months later, the Knickerbocker Athletic Club organized a marathon race from Stamford, Connecticut to The Bronx, and in March 1897, the Boston Athletic Association held the first-ever Boston Marathon. From there, the marathon race spread all over the world.

If you signed up to participate in a running race, such as a marathon or a 10K, your personal journey could also be seen as three acts:

No one, from the fast runners hoping to win the race to the people just hoping to finish, has any idea how their race is going to go. As the race day draws near, tension builds, whether you feel it or not, and the only thing that releases all that tension is the actual running of the race. When it’s over, whether you’re happy with the result or not, it’s over.

The first time Ray Yoder ate at a Cracker Barrel, he wasn’t that impressed. He was in Nashville in 1978, helping to set up an RV show at the Opryland Resort and Convention Center, and there was a Cracker Barrel nearby. So he ate there, and it didn’t exactly blow his mind. But he had a job delivering RVs across the country from a manufacturer in his hometown of Goshen, Indiana, and he spent a lot of time on the road. So he found himself in a lot of places with Cracker Barrel restaurants. He kept eating at Cracker Barrels, and they started to grow on him.

He was almost always on the road by himself while his wife, Wilma, was at home raising their four children. When all the kids had finished school and moved out of their house, Wilma started to join Ray on the road. Around 1993, they realized they had eaten at lots of Cracker Barrel restaurants, and decided to try visiting all of them.

By August of 2017, the Yoders had both turned 81, and had visited almost all of the 600-plus Cracker Barrel restaurants in the United States, Ray mostly eating blueberry pancakes if it was breakfast time, meatloaf if he was there for lunch or dinner, and pot roast if it was Sunday. Cracker Barrel caught wind of Ray and Wilma’s quest and flew them out to Portland to visit the newly-opened restaurant in Tualatin, Oregon, Number 645. A line of applauding Cracker Barrel employees greeted them at the door, with a bouquet of sunflowers and roses for Wilma, and custom aprons for both of them.

Their journey had taken them to 44 states, and Ray estimated they had driven more than 5 million miles. “Well, everybody does something, usually anyway,” Ray said. “So we thought we would do this and it would be fun.”

At the 2017 Run Rabbit Run starting line at the base of Colorado’s Steamboat Ski Resort, 314 runners stood in the corral, every one of them hoping to finish the 102.5-mile race. Only about 58 percent of them would actually make it to the finish line.

The Run Rabbit Run is not typically mentioned as one of the hardest ultramarathon races in the United States, and 2017 wasn’t an abnormally hot or difficult year. Generally, about one-third of people who start the race each year don’t finish for one reason or another: injury, gastrointestinal distress, dehydration, exhaustion.

No one standing in that starting corral believed it was impossible for a human being to travel 102.5 miles of mountainous terrain in 36 hours. Everyone was aware that it was something humans did. They had heard of these types of races before, maybe knew someone who had completed one, or maybe they’d even run this one in a previous year and had fun doing it. They believed they could be one of the people who earned a Run Rabbit Run 100 finisher belt buckle, and that’s why they were standing just inside the red start/finish arch, pacing, chatting with other runners, shaking out their nervous legs.

I was there too, standing in the corral, anxious and jittery, with a race number pinned to my running shorts, as the morning sun started to warm the high-altitude air. Like everyone else, I knew that people, arguably “normal” people who had day jobs and families and credit card bills, were perfectly capable of running a 100-mile mountain ultramarathon in 36 hours. It was something that had been done plenty of times before by human beings just like me.

Well, maybe not like me. I wasn’t sure if I’d be just like them, a finisher. And I’d been unsure for eight months, since I’d paid my entry fee.

I was still unsure when the gun went off and the crowd of runners started shuffling forward through the starting arch. I started jogging with them, and no one tried to stop me, so I just kept going.

Source link