No products in the cart.

Outdoor Adventure

Can Strength Training Protect You from Running Injuries?

Heading out the door? Read this article on the Outside app available now on iOS devices for members!

Download the app.

The best way to prevent running injuries isn’t to waste your time stretching or searching for the perfect shoe; it’s to get strong. That’s where the zeitgeist has been headed over the past decade or so, as old ideas about injury prevention have produced disappointing results in studies. The rationale for strength training, by contrast, is seemingly unassailable: injuries occur when more stress is applied to a tissue than it can absorb, so strengthening the tissue should ward off injuries.

But that claim, too, should be treated with caution, according to a new systematic review of exercise-based prevention programs for running injuries. In Sports Medicine, a research team led by Richard Blagrove of Loughborough University in Britain sums up the available evidence. Blagrove, for the record, is the author of Strength and Conditioning for Endurance Running and has worked with plenty of elite runners on their strength routines, so it’s not like he’s an anti-strength-training zealot. I’ve written before about some of his previous research on strength training and running economy. But the overall picture on injury prevention is underwhelming—although, as Blagrove and his colleagues point out, there are reasons for optimism and some intriguing avenues for future research.

As with all systematic reviews, the first challenge is finding studies that meet your criteria. In this case, one of the key hurdles was ensuring that the subjects in the study were, by some reasonable definition, runners. Previous reviews of the topic have included military studies where running only made up a small fraction of overall training, and injuries sustained during other training activities were counted as “running injuries.” For the new review, they insisted that running had to be the subjects’ main training activity, comprising at least half their training time.

They were able to include nine articles with a total of 1,904 subjects—which, for a tricky topic like running injuries, isn’t a lot. The exercise interventions were all over the map: strength exercises like lunges and squats, plyometric hops and jumps, core routines, foot strengthening, and so on. Overall, perhaps not surprisingly given the wide variety of regimens, there was no significant benefit for the exercise groups compared to the control groups in injury risk (what proportion of subjects got injured during the studies) or injury rate (how many injuries they suffered for a given amount of running).

That, for now, is the state of the evidence. As always, we’re left hungry for more. What are the injury benefits of a straightforward strength-training routine? Given that this is among the most common forms of supplementary exercise among runners, you’d think we would know if it helps, but there’s almost no evidence either way. That’s important, Blagrove and co. point out, because there is robust evidence that this approach works in other sports like soccer. That doesn’t mean it will work in running, since the injury mechanisms are different, but it does suggest that it’s worth finding out.

One intriguing pattern in the data is that the three studies that produced the lowest injury risk also happened to be the three studies where the exercise routine was supervised rather than just assigned to be performed at home. Previous research has tended to find that people get bigger gains when they have a spotter or a personal trainer looking on. That could be because they dig a little deeper; or in this case, it could be that this is the only way to ensure people do the exercises at all. Sports medicine doctors and physical therapists often laugh about the patients who come for a follow-up visit claiming that they’ve been doing their assigned exercises religiously… but when they’re asked to demonstrate them, search for the piece of paper where the exercises are described. Exercises can only work if you actually do them, needless to say.

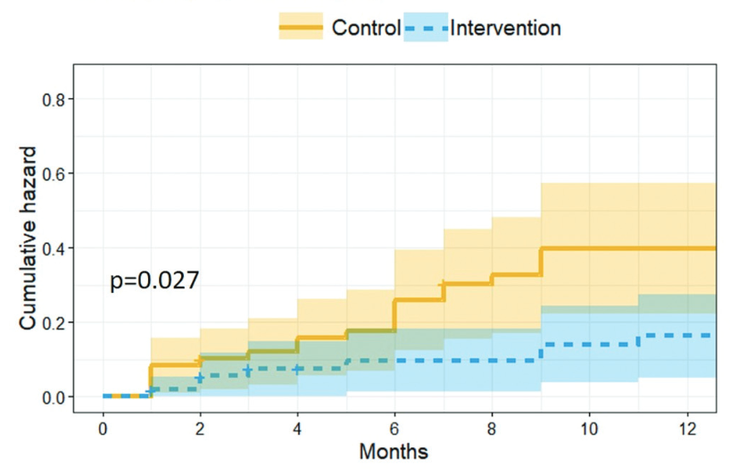

It’s also worth noting that Blagrove and his colleagues were particularly intrigued by a 2020 study from the American Journal of Sports Medicine that used foot and ankle strengthening, including exercises like “foot doming,” based on the concept of a “foot core” providing stability to the rest of the body. In that study of 118 runners in Brazil, the control group was 2.4 times more likely to develop an injury during the one-year follow-up period. The survival graph from that study, showing the cumulative injuries for the control group (solid line) and foot-strengthening group (dashed line), is certainly compelling:

But the whole point of a meta-analysis is to pool more than one study, to increase sample size and reduce the risk of fluke results—and of investigator error or bias. One of the minor details in the meta-analysis: there were actually two other studies that met the inclusion criteria, both by the same research team. But when Blagrove’s team dug into the studies, they found identical baseline data—the same age, height, body mass, BMI, running experience, and biomechanical parameters—and identical injury occurrences… even though the studies had different sample sizes, durations, and exercises. The authors didn’t respond to questions about their data, so Blagrove’s meta-analysis excluded them.

The bottom line? We can’t say for sure, at this point, whether strength training or other forms of exercise lower your risk of getting injured while running. The logic is sound, and the circumstantial evidence from other sports is suggestive. Maybe more importantly, there’s also solid evidence that various forms of strength training improve running economy and boost your long-term health. It would be nice to get some injury prevention as a bonus, but the package is already pretty enticing.

For more Sweat Science, join me on Threads and Facebook, sign up for the email newsletter, and check out my book Endure: Mind, Body, and the Curiously Elastic Limits of Human Performance.

Source link