No products in the cart.

Outdoor Adventure

How a Snowboarder Survived for 20 Hours After Being Buried in an Avalanche

Heading out the door? Read this article on the Outside app available now on iOS devices for members!

Download the app.

Avalanche safety, like sex ed, isn’t really about abstinence. People are going to venture into the mountains, so the challenge is to minimize risk, take appropriate countermeasures, and understand when conditions are too dangerous to proceed. Still, things sometimes go wrong even if you’re following best practices, at which point the objective shifts to maximizing your odds of surviving and being rescued. It’s this last topic that’s the focus of the Wilderness Medical Society’s newly revised avalanche guidelines, published by an international team of experts in Wilderness & Environmental Medicine.

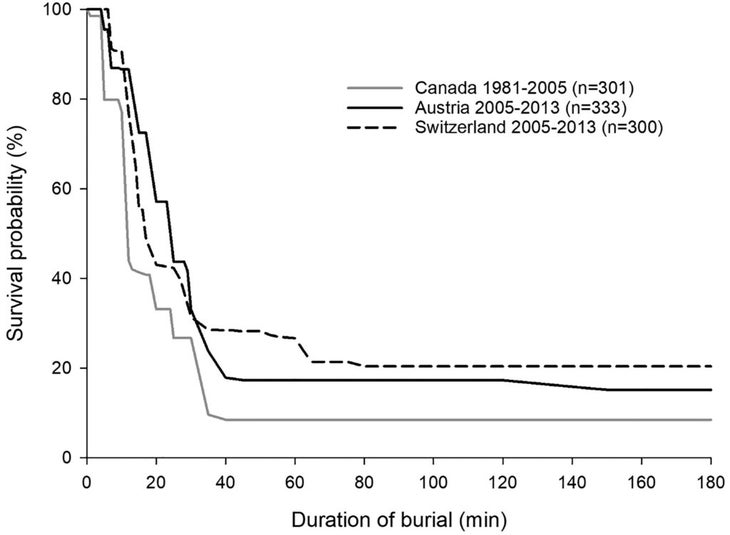

An estimated 300 to 500 people die each year in avalanches. The average figures in Europe and North America are about 130 and 36, respectively; numbers in the rest of the world are rough estimates. Three-quarters of those people asphyxiate; the other quarter succumb to traumatic injuries. Not many people die of hypothermia, because they don’t last that long. Time is of the essence: you’ve got a 90 percent chance of surviving if you’re extricated within 15 minutes, but that drops to 30 percent after half an hour. The deeper you’re buried, the worse your odds.

The new guidelines (which are free to read online) delve into the minutiae of the factors that can affect survival in an avalanche. You want a metal rather than composite shovel, for example; a curved blade will allow you to clear snow 47 percent more quickly than a flat blade. But the most surprising details are found in a never-before-published case report from more than two decades ago, published in parallel in the current issue of Wilderness & Environmental Medicine by some of the same authors, that illustrates the limitations of the averages reported in the guidelines.

In January 2000, three friends were snowboarding in the Western Austrian Alps. It was 14 degrees Fahrenheit and had been snowing heavily for three days. At 2:45 P.M., two of the friends decided to descend off-piste from the summit in deep powder, some 6,500 feet above sea level. Three hours later, the third friend, who had descended on the groomed slopes, reported them missing. Rescuers soon realized that the pair had been buried by a spontaneous slab avalanche. (There are some aerial pictures of the terrain in the case report.) As night fell, visibility was poor and avalanche risk remained high. The search and rescue operation was suspended at 11:30 P.M., and another two and half feet of snow fell overnight.

The next morning, rescuers resumed searching at 7:30 A.M. Three hours later, an avalanche dog located the first snowboarder; his airway was blocked by snow and he had likely died within less than half an hour of being buried. The second victim, a 24-year-old male, was found ten minutes later, buried under 7.5 feet of snow. His ski goggles had slipped over his mouth and nose when he fell, creating a small air pocket. There was an air connection to a larger pocket around a nearby rock at ground level. He had been buried for 20 hours and the temperature measured in his ear was 72.5 degrees Fahrenheit, but he was alive and responsive.

After being helicoptered to hospital, his core temperature was measured at 75.4 Fahrenheit. In addition to warming him up, the doctors needed to deal with other issues like low blood pressure and heart rhythm disturbances. They figured he was dehydrated, so they gave him nine liters of fluid. That turned out to be a mistake, and when fluid started accumulating in his lungs, they stopped the rehydration protocol. He had some “nonfreezing cold injuries”—the modern term for trench foot— which mostly resolved after a few days, but no frostbite. There was no sign of brain damage, and after four days he was released from the ICU.

In the case report, the authors—physicians in Austria and Switzerland, led by Bernd Wallner of the Medical University of Innsbruck—extract some lessons for the care of avalanche victims. There are some differences in the current guidelines compared to what was standard in 2000 in the details of how such patients should be rewarmed, where needles should be inserted, and so on. But the main point of interest is the extraordinarily long burial time.

Here’s a graph from the new WMS avalanche guidelines (adapted from this 2011 study in the Canadian Medical Association Journal), showing survival probability as a function of burial duration:

It’s a pretty steep curve, and the odds are grim after half an hour. And this graph only extends to three hours. The Austrian snowboarder was buried for 20 hours! In fact, according to the authors, there are only two known cases with longer burial times in comparable conditions. In 1960, a 59-year-old man in Canada survived after 25 and a half hours under the snow; and in 1972, a woman in Italy survived for 43 hours and 45 minutes.

By far the best way to survive an avalanche is not to get caught in it. Don’t venture into avalanche territory without adequate knowledge, training, and equipment. Even if you have all those things, err on the side of caution. If you do get caught in one, the WMS guidelines weigh the relative merits of a long list of countermeasures that might raise your odds of survival, ranging from airbags to avalanche transceivers to covering your mouth with your elbow to create an air pocket. After that, it’s a question of how quickly rescuers find you. Time is of the essence. But if there’s one lesson for anyone who finds themselves part of a search-and-rescue effort to draw from this case report, it’s that even as time passes and the odds get longer and longer, they’re not zero. Keep digging.

For more Sweat Science, join me on Threads and Facebook, sign up for the email newsletter, and check out my book Endure: Mind, Body, and the Curiously Elastic Limits of Human Performance.

Source link