No products in the cart.

Outdoor Adventure

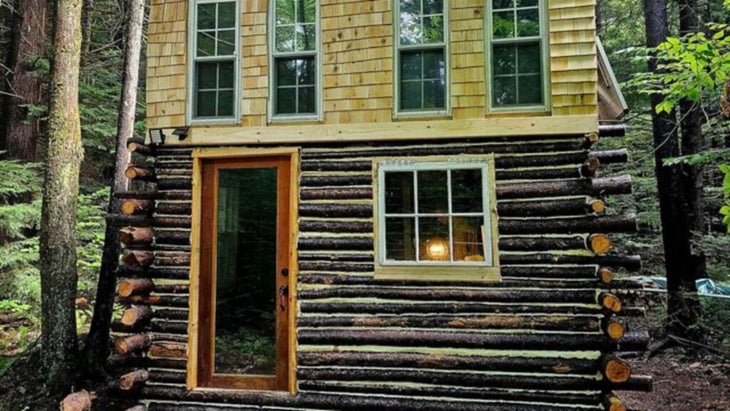

How I Built an Affordable Log Cabin in 7 Weeks

Josh Drinkard always wanted to build his own cabin. Growing up in suburban New Jersey, he’d wander to a small strip of woods near his childhood home and spend hours constructing forts and treehouses. When he moved to New Mexico as an adult, Drinkard, the IT Operations Manager at Outside Inc., bought 2.5 acres of land in the mountain village of Truchas, about 30 miles north of Santa Fe. There, he took on his first effort at building a very simple cabin with the help of a friend who was an unlicensed contractor and taught Drinkard framing and building basics.

In 2021, Drinkard and his wife, Saraswati Khalsa, started looking at New England as a place to move once their three children were grown. After scouting around, they settled on 25 terraced, hardwood-filled acres near Halifax, Vermont, not far from the Massachusetts border.

Over the past three years, Drinkard has spent vacations building a cabin near Halifax, with the help of his wife, teenage son, and one of his daughters. After a cumulative seven weeks of effort, they can now stay there for long periods, although it still lacks internet service, a shower, and a toilet.

Learning the ins and outs of building a small log cabin in the woods is no small feat. We asked Drinkard to talk about what the project entailed and what skills are required to turn a cabin-building dream into a reality. This is what he learned.

How Big Is the Cabin?

It’s still a work in progress, but right now it’s a one-room cabin with a loft. Two people can sleep up there comfortably. The interior is just 12 feet squared. We use the lower room as the living room and kitchen. Another two people could sleep there with a foldable futon.

Why Did You Choose Vermont?

We bought this property without any services or electricity, so the price was below the national average per acre (which was about $3,000 at the time, according to Drinkard). I love the location and especially the lush green forests. We also love skiing and whitewater rafting and can do both near here; the closest mountain is Mount Snow, 18 miles north, and the closest flowing river is the Deerfield, to the west.

We liked that it’s not far from a town with big-box stores—Greenfield, Massachusetts—and that you can catch a train from Brattleboro, Vermont, to New York City. We thought that if the kids are in college, or after, if they wanted to take a train up, that would be convenient.

And I like Vermont in general. Everything has a small-town feel. There are no billboards. And it’s similar to northern New Mexico in that it’s rural and very liberal.

How Did You Get Started With the Build?

We found a spot that was flat and open. There was a little meadow on the property just big enough for a cabin, so we didn’t have to clear it. We knew we’d use the hemlock trees from the surrounding forest. I was told hemlock resists rot pretty well.

I knew I’d have to find a cheap 4×4 vehicle to leave out there, and we only had a few thousand dollars to work with. In Vermont, good pickups in that price range were all rotted out, so I settled on an old Lincoln Navigator in New Mexico that had been stolen and recovered; its interior was beat to shit. I welded a receiver hitch in front, to use as a winch and a pushbar, and I also fabricated a roof rack big enough to haul 16-foot-long lumber and plywood sheets. Then I drove it out to Vermont.

We decided to use a butt-and-pass method to build the cabin after a lot of time looking at YouTube videos. Butt-and-pass cabins go up quickly, but the drawback is you need a ton of expensive lags to connect the walls to each other and each log to the ones below.

We used logs for the whole first level of the cabin. The first year, the family came out for four days and we felled trees and placed and leveled the bottom four logs. After they left, I stayed another six days on my own and threw up the first 12 rows of logs—they weren’t that heavy—plus the floor and a temporary roof to keep the snow out.

The next year, we got the structure height to about eight feet. At this point, we started using two-by-fours for the loft level. I traded an old laptop of mine for a bunch of small windows and a door.

After the entire structure dried, we hung shingles on the front. I installed a water-catchment system and solar panels—both are sustainable. We built the loft platform inside and scraped and sealed all of the logs. And I built a small shed with scrap materials and installed more windows on the first floor.

What Was the Hardest Part?

Felling trees for the logs and dragging them around 100 yards to the build site was exhausting. And I’m not in awful shape.

Using a 16-inch battery-operated chainsaw, we took down 30 to 40 relatively straight, light trees on the first trip out, but they kept getting hung up in the tight forest canopy. Then we cut these to 12 and 16 feet and dragged them to the site. It took a few days. The next time we were there, the following July, we cut another 30 or 40 trees.

Does the Cabin Have Plumbing and Electricity?

One of the last things I did when I was there was put in a rainwater-catchment system. The rainwater goes from the roof to a gutter and through a small-screen filter to a 300-gallon IBC (intermediate builk container) tank. The tank was repurposed—it used to hold soy sauce—and someone sold it to me. I’m gonna have to plumb from that tank to a sink and an outside shower. There’s no toilet—we probably will get an outhouse but right now we’re using a bucket with a toilet seat on top.

“Except for needing help fixing the road, we were able to do everything on our own.”

For electricity, I have a small solar setup: two 100-watt panels and a solar battery that’s good enough to charge things and for basic lighting. The great thing about these is they’re upgradable; I just need to get more batteries and panels to turn it into something more robust that could handle, like, a fridge.

What About Heat?

I brought out a woodstove from New Mexico but decided it’s too big and that it would heat us out—that’s a mistake I made with the cabin in Truchas, too—so I’ll probably buy a small one.

Did You Have to Troubleshoot Any Unforeseen Issues?

It rained a lot one trip, in July, and the road, which is unmaintained, was turning into a rutted off-camber mess. I was having to winch up in several places, and I blew out the Navigator’s 4×4 low. So we found a local heavy-equipment operator and hired him to take down some trees and smooth out the road. But this is an investment for us. Having a small functional cabin with a roughed-in road will increase the property value by more than what we’ve spent.

Also, except for the initial time I drove the navigator out, we’ve flown. And every time, we fly with the power tools. I check the chainsaw, the circular saw. You can’t check the batteries, so I have to carry those on.

How Did You Cut Costs?

One of our challenges was thinking up a good chinking method that wouldn’t take an entire month. There are maybe 80 trees in the structure—because they were smaller in diameter, we needed more, which also meant 80 gaps to fill. Concrete mortar was out, because we didn’t want to haul water up from the stream and mix cement. Log Jam was out, because it’s too expensive. So we used a product called Great Stuff Pestblock. This is a spray foam with a component that tastes sour, so bugs and rats don’t want to chew through it.

Pestblock worked better than I imagined, but it’s gonna yellow real bad and I’ll likely have to paint it. I tried putting floor polish over it, to keep the gray color, but it didn’t work.

Also, we didn’t strip the bark off the logs. It looks cool, but bark holds moisture and the logs can rot. After we completed the first floor, they sat for a year, and I thought that if we wire-brushed the logs after a year or so, we could then use floor polish to seal them. So far that’s been working great, but only time will tell if we have any rot. I might know in a few years.

We also stayed in a nearby campground much of the time when we were working on the cabin.

Did Your Family Like Being Involved?

We just gave my son, Mason, a nice RAV4, so we forced him to come out and be our indentured servant. After the second trip, he told me I’d worked him pretty hard but that he had a great time. He can do most jobs independently after a little training. One of our daughters also did a lot of work the first visit, carrying logs.

Saraswati, my wife, is really good at certain things like angles or eyeballing whether something is level. My eyes are awful. Also, I can have a short fuse. At the beginning, I’m fine, but after a week, it grows shorter. And Saraswati will really push to get things done when I’m ready to quit, so we get a lot more done when she’s around.

On the flip side, I have to bring her back down to earth on structural realities. She’s always form over function, and I’m the opposite. For example, we had a full-size door, but I realized that fitting it would cut too many logs on one side and compromise the structure. So we had a bit of a fight about that, because I wanted to cut the door and make it shorter. That’s what we ended up doing.

What Are You Proudest Of About the Cabin?

We did this on the cheap and haven’t splurged on anything so far—though having internet out there will be a splurge. The cabin’s a pretty basic structure, but I’m OK with that. And except for needing help fixing the road, we were able to do everything on our own. There’s no cell-phone access out there, so if you run into a jam, you just have to figure it out.

Estimated Costs for the Cabin

Land and Annual Taxes: $78,000

Building Supplies: $8,000

Driveway: $7,000

Eventual Internet Setup: $700

Flights, food, fees to stay in the nearby campground before the cabin was ready: $5,000

Total: $98,700

Tasha Zemke is Outside’s managing editor and a member of Outside Online’s travel team. She appreciates beautiful, and especially ancient, architecture but can’t imagine building a structure of any kind, given her loathing of giant home-improvement stores.

Source link