No products in the cart.

Outdoor Adventure

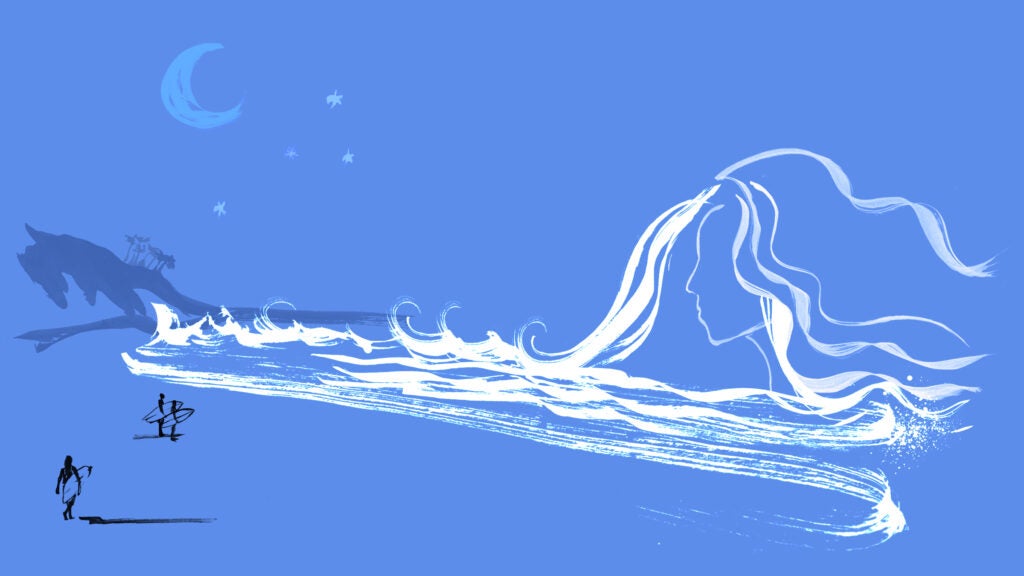

How I Transformed Myself Into a Chill Ocean Girl

I sat anxiously in my pickup truck on Pacific Coast Highway, waiting to go nighttime lobster diving with a guy I just met.

At 8:30 P.M., Liam arrived in his eighties Jeep Wrangler. It was dark, but passing headlights allowed me to spot his wavy hair and goddamn fraternity sweatshirt. He skirted past me as I opened my car door, busying himself by inspecting the gear in my truck bed—occasionally speaking, half to me, half to the sky. He told me to sit tight while we waited for the others. Others?

Then a gargantuan Ford Raptor with a blinding overhead light bar pulled up. A small dude in a camo hoodie and a trucker hat hopped out. His passenger door burst open and out popped an overly excited teenager whose hair resembled charred tumbleweed. Classic. The Aquatic Country Boy and his sidekick strolled over to Liam and exchanged Neolithic handshakes. The boys cordially shook my hand, asking if I had done this before. I nodded, “A bit,” and adjusted my weight belt, securing the knife in its sheath.

I spent most of my childhood playing in saltwater.

I was raised in San Diego, but this was abnormal for my family. I have no memories of my mother allowing the waves to reach past her ankles, and my father never learned to swim. I would pad along into the water and plunge headfirst into the sea. My mother would pace along the shoreline yelling, “¡Ten cuidado!” She always wondered why I turned toward the ocean and not her.

The first time I caught a wave, I was 12 years old in a red and blue rash guard and pigtail braids. Some dusty blonde old-timer, a friend of a friend of my father’s, sat on a longboard behind me and pushed me into a mashed potato wave. I was waltzing on water. Hell, Jesus Christ himself had nothing on me. I dove off the board and let the white water wrap my tumbling torso.

I learned to seek out rip currents. They saved me energy—sucking me out quickly, protecting my endurance. Jumping into a rip on a surfboard, I could make it past the set waves without getting my hair wet.

I remember sneaking out of my house in high school to go night surfing during El Niño conditions. I took four friends, all of us piling into my mother’s old Chevy Tahoe. We rolled out of the driveway with the headlights off. The impatient Santa Ana wind tugged at our glow stick necklaces and tickled our cheeks. The full moon even came out to play that night, allowing us brief previews of the dark walls of water approaching before the waves would break. Every time someone got caught in the rinse cycle, the glow stick luminescence gave color to the white water. We were the only ones out, giggling and ducking below the surface when the border patrol would drive by on the sand. It was near midnight—a perfect time to catch people swimming to America. We saluted their tail lights with paint-chipped middle fingers. But to be fair, my grandfather did stagger out of the surf on a beach three miles south of where we were. Forty years earlier. I guess he wasn’t the only one.

The more time I spent in the ocean, the more I craved it. My parents feared the physical dangers, like lethal currents and sharks. I never did.

The demons in my head were heckling locals and ostracizing beach boys. Maybe I would have been less bothered if I saw other people in the water who looked like me—girls with brown skin and dark hair, their mothers yelling at them in Spanish from the shore. My imposter syndrome grew as the years went on. In the faces of every male surfer, I saw remnants of cupcake-blonde 13-year-old boys in matching rash guards, trash talking foam board users and flaunting their fiberglass shortboards. They were kids who learned about the ocean from their parents. I should’ve known they were often full of shit, but as a shy tween, I let them take my waves. Maybe if I didn’t piss off the local groms, they would let me into their little club.

Once, while in line for the bathroom at a party, I overheard a cluster of half-baked surfer bros berating someone’s Instagram photos. Their frosted tips touched as they crowded around one phone screen.

“All her photos are in a fucking thong bikini.”

“She doesn’t even surf!”

Their words raked over her body like they owned her. I peered through one of their elbow crevices to see what they were laughing at. She was my friend.

Like a lobster, I adapted to survive. Lobsters evolved to swim backwards, compressing their tails to propel themselves away from predators; I learned to live in a state of constant apathy, unbothered and unoffended. Lobsters pee out of their faces to attract a mate; I found safety in emotional inaccessibility. I said the names of beach towns—San Diego, San Clemente—like a gringa so I could be understood. I feigned oh yeahs when the white boys showed me their tanned vacation photos and asked me whether they looked Mexican. I knew I wasn’t ever going to look like the Southern California stereotype, but I could play the part.

Lobster diving found me in Mexico. I was 19, sitting at a restaurant in Tijuana with my family. Where I come from, we cross the border for restaurants and the vet’s office. Vámonos a Ensenada means brunch on a Sunday.

Two men emerged from the sea hauling foot-long reddish-orange lobsters—bugs, as they’d probably call them—in nets strapped to their waists. I couldn’t stop staring at them, seeds of curiosity already taking root. I let YouTube teach me about a world where you enter the sea hungry and exit with dinner. I studied the way that divers cleaned their gear and prepared for oxygen deprivation. I saw the lobster as a tangible validation of my authenticity, my ocean-badass certification.

My first few attempts at freediving were a kookshow. I had a mask and bodysurfing fins. I dragged a friend along with me, but the best I could offer her were swim goggles. I told her to bob around at the surface. I would poke around the limpets and near the tiny anemone communities in the deep intertidal zone, not yet venturing into the kelp kingdoms.

Over the months that followed, I swam deeper into the bull kelp, testing the upper limits on breath holds and finding animals I had only ever seen in documentaries. Sheep crabs. White seabass. Hermaphroditic sheepshead. I’d try to join schools of anchovies, but they would just scatter and regroup ahead of me. I loved laying in the eel grass looking up at the surface, little crabs trying to pinch my ass beneath me. When I couldn’t be in the water, I’d watched Kimi Werner on YouTube take hundred-foot drops and artfully transform into an underwater predator. Unable to afford any proper training, trial and error became my method.

I had been diving for nearly a year when I had my first real scare, during a dive in college.

I spotted a lobster trap with monstrous bugs and I dropped down to get a look. On my way back up, a tug halted my ascent attempt. Oh, I thought, looking down. The small gauge, used to determine a lobster’s legal size, had been dangling from my belt and got caught in the metal squares of the cage below me, the curves of my tool hooked perfectly inside the trap.

The chest convulsions began. That didn’t mean I was out of air yet, but a panic welled inside me. I was 20 feet down. The current began pushing blades of kelp into my face. I tried to surface again, hoping that with an upward push, the gauge would slip out as confidently as it had slipped in. I was met with a jolt.

My trembling fingers lacked dexterity as they battled the kelp, my knees banging against the black bars of the trap. Relax. Turn it sideways, you idiot. Freeing my gauge, I shot to the surface, panting frantically. That was close. I looked around. My friends splashed happily in the intertidal zone. They would’ve had no idea.

Suited up around Aquatic Country Boy’s vehicle, we planned the dive. I eyed Liam carefully, painfully aware that I knew nothing about this guy, other than that he was a strong surfer and we had a mutual friend, whose car we’d met in briefly only days before.

Sidekick spoke up, “How do we know if it’s legal size?” He must be new.

I held up my silver lobster gauge, “You measure the carapace exoskeleton that covers the cephalothorax, which means the head—from the horns to where the tail starts.” All three boys looked at me. Liam smiled. “Cephalothorax. We must measure the cephalothorax,” he mocked in a high-pitched, nasally voice. I cracked a smile.

In a five-millimeter suit, I strap 10 pounds to my waist, which will allow me to stay near the seafloor without much exertion. More effort means less oxygen. I minimize movements by bending at the waist and avoiding fin thrashing on the dive down. Lobster gloves are lined with Kevlar that protects your hands from the piercing underside of the Pacific spiny lobster tail, which contracts when they try to swim away.

We stood at the water’s edge waiting for the one half-ass wave to pass. Liam turned on his flashlight. I did the same, pretending I’d done this countless times before. I hadn’t told him I’d never gone diving at night. He shoved his neoprene feet into his fins and held my gaze as he backed into the surf. Intrigued by his sense of adventure, I followed him into the dark water.

I spotted lobster after lobster, pinning them to beds of eelgrass or the seafloor. Most were juveniles, too young to keep. Following the light emanating from my right hand, I scanned one rocky algae structure, looking for the reddish twitch of an antenna or an arthropodic shuffle, telltale signs of a lobster on the move. I spotted a sneaky antenna disguising itself amongst the grass. Going in half-blind, I shoved my palm down into a crevice, hoping I wouldn’t pull out a moray eel. Feeling the familiar ridges of the carapace, I smiled and pulled up a twitching lobster. I turned it over. A big male. Lobsters gripped my wetsuit through the bag hanging from my belt as we swam, passing dens of drowsy orange garibaldi.

We stumbled out onto the shore, drunk on saltwater and high off hunting adrenaline. The wetsuits kept our bodies lukewarm, and the weight belts fought every step we took. Liam and I dragged our feet, letting Aquatic Cowboy and Sidekick get far ahead. He spoke softly, making me giggle while being careful not to wake the empty stilted beach homes above us.

Liam and I let our friendship bud into something more, then set it on fire. We played amongst the algal fortresses and collected bugs and made lobster mac and cheese.

My first octopus friend was a yellow and blue beauty. She took her time crawling up my arm as I shouted for Liam to come see her. She and I watched each other as she tinkered with my snorkel, her body splayed out across my chest. She never inked. On many occasions, Liam would get his hands on a horn shark. He would splash around, wrestling it delicately. I would pull my mask down and tread next to him shaking my head. He would later show me teeth marks on his bare limbs as we lay in bed, and no matter how many times I scolded him for getting what he deserved, Liam would shoot back a lopsided grin and laugh, “That’s the point.”

By the time Liam came around, I was well-versed in how to interact with aquatic boys. I could easily interpret the various meanings of chaaaa and duuuude depending on the tone of utterance. But years of adapting to emotionally unavailable ocean-boy culture left me emotionally stunted. I was the chill girl who always carried extra dive gear and knew where to find the leopard sharks, but I couldn’t be honest with myself—or the boy I loved.

Many full moons after that first night dive and three months after our college graduation, he asked me what I wanted. He’d been distant all night. I wanted to appear unaffected by his indifference, ashamed by how emotionally attached I’d become. I was suffocatingly concerned with maintaining the facade of a chill girl, worried that the strength of my feelings would make me an inconvenience. I felt like I was being rejected by ocean culture all over again. The imposter syndrome had washed up on the shore at my feet. In a panic, I blurted out friendship.

In my new landlocked home, I practice my I love you’s on firs and larches. Sometimes I cry.

Alone atop a mountain and pretending hard enough, I can just make out the sea. Bug season began a few weeks ago.

Source link