No products in the cart.

Outdoor Adventure

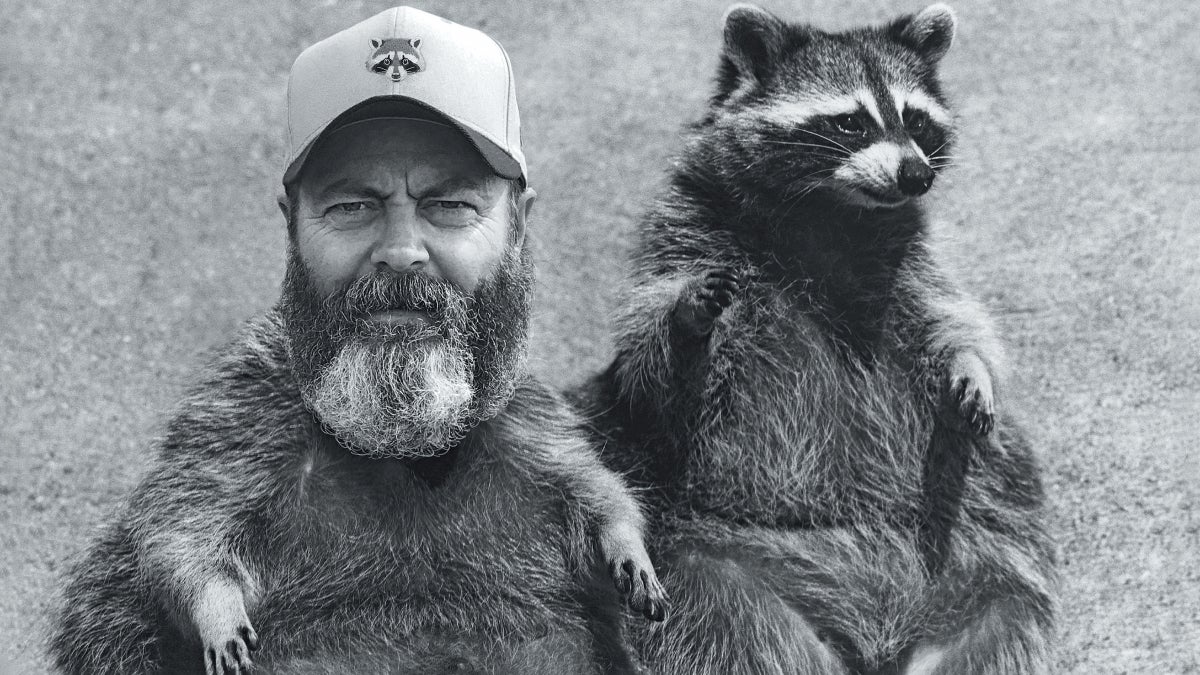

How Not to Trap a Raccoon, a Nick Offerman Confession

A dead possum. Damn my eyes. I had gone through all of that rigmarole and trial and error with my cage trap, doing my damnedest to humanely relocate a bothersome raccoon, and this is what I get. Although I bear no particular love for possums—they are among the creepiest mammals around—my heart was in my throat as I considered how best to dispose of this one’s corpse.

Let me rewind a bit. I grew up in a rural part of Illinois, where I generally loved the animals I encountered around my home and on my grandparents’ farm, including a yearly crop of meat hogs. And while I was not a hunter myself, I valued the role of hunting and fishing in the subsistence economy of my family and community. As an adult, I dug into the writings of Wendell Berry and Aldo Leopold, which further shaped my environmental ethos. But all that affection for other creatures went out the window when I suddenly found myself squaring off in a turf war with a raccoon.

The setting was a vacation house my wife and I had in a redwood forest of Sonoma County, California, where a large bed of hydrangea in the front yard was being aggressively excavated at night. It appeared as if a befuddled band of wee pirates had been digging blind for a long-lost treasure chest. I conferred with a botanist friend, and we agreed that it must be a raccoon hunting for delicious grubs.

I decided I’d catch and release, far away, this nocturnal mischief-maker, so I went to town and bought a large cage trap, intending to capture the little bugger and relocate it to the wilderness. I was actually looking forward to the project. It seemed like a fun challenge, something Huck Finn might enjoy. I did a bit of online research, but I also thought: Come on, I’m a country kid. How hard could it be to outsmart a so-called trash panda?

Extremely hard, it turns out. As I would later learn, studies show that raccoons are highly intelligent—likely smarter than your cats, which are pretty darn smart. The various obstacles we’ve developed to keep them out of our human spaces, like Toronto’s $24 million, raccoon-proof waste bins, seem to have only enhanced the animal’s problem-solving skills. Perhaps this is how we ended up with that super raccoon who climbed a 25-story building in Saint Paul, Minnesota, in 2018.

I set up my trap near the hydrangea-strewn battleground, baited it with peanut butter on bread, and turned in for the night. When I came out to check the trap the next morning, the bait was gone, but the trap stood unsprung. Son of a bitch. Rocky Raccoon had drawn first blood. I immediately became fixated with a visceral desire to destroy—um, I mean, gently transplant—this charming rascal.

It took me three more nights of escalating techniques before I was able to catch something. My most ambitious innovation was camouflaging the entire cage structure, especially the wire-grid floor. I covered it in mulch and forest detritus, which I then compressed and covered again with another layer to match the ground surrounding the cage site. I performed all manoeuvres (we’re into some MI6-level stuff now, hence the British spelling) wearing gloves, so as to leave no scent on the apparatus.

I also upped my baiting game by leaving a trail of a few pungent crumbs leading into the trap: old bacon, a chicken leg, and the payoff prize—half a piece of pepperoni pizza. Inside the tantalizing slice was a wire securing it to the mechanism that released the latch and sprang the door shut.

I thought: Come on, I’m a country kid. How hard could it be to outsmart a so-called trash panda?

I awoke on the fourth morning before the sun was up, feeling like a kid at Christmas. Within minutes I was out in the yard, skipping to my trap because I could see from the house that the door had been sprung shut. My elation was quickly quashed, however, as I drew near and realized that I had not trapped a raccoon but a creepy old possum. Not only that, but the damn thing was dead. Maybe the chicken was bad? The critter wasn’t breathing, and it didn’t stir when I gave the cage a brusque kick.

There was little choice but to get rid of it in the woods. But as I picked up the trap, the animal suddenly hissed and cowered back away from me. I very nearly soiled my britches as I shouted and dropped the cage, because of course the goddamn thing was merely playing possum. Some country boy I turned out to be. I had seen many possums in my day, including a spooky one in Silver Lake that my friend Pat insisted had my face, but I’d never had occasion to see one pull its namesake stunt. After checking my shorts for terror stripes, I spoke a few select, congratulatory words to the possum and set it free where we stood, watching it haul ass out of sight.

I resumed my mission, which by now had become a blinding obsession. I set my jaw, cleaned out the trap, and re-created my successful combination of baits and set design, adding some strategically located trash spilling from a “tipped over” can. Frustration ensued for another four nights. With each failed effort, I adjusted and polished my techniques and tried experimenting with different locations in the yard. It got to the point where, with each new layer of branches, moss, and tree duff, I had nearly fabricated a large burrow. Then, the final touch: I swapped out the pizza for a smoked pork-chop bone, which still had a few nibbles of meat left on it.

Ha ha! Another skipping morning traipse out to the tripped trap, and this time I could see, even from a good distance, that it was no stupid possum. Suck on that, Mr. Raccoon, you fool! Who’s the dummy n—oh, shit. I had a fox.

The beast was gorgeous: mottled, with patches of silver and red. I was spellbound. Then it growled at me. The noise sounded like an idling chainsaw burning an overly rich fuel mix. This magnificent mammal was letting me know that it would like to vamoose, and I was only too happy to oblige. I released it on the spot and watched as it vanished into the trees.

After another week of dogged fidelity to my project, I finally trapped my prey. And it was even a raccoon this time! I caught a large boar (male), then a sow (female), then a smaller boar. I drove them some 15 to 20 miles away, to a remote spot, where I let them run free. I felt ten feet tall with triumph.

Later I was informed that relocating raccoons is illegal in some states, due to concerns that include the spread of disease and disturbance of ecosystems. In California, the Department of Fish and Wildlife mandates that the animals be “humanely euthanized or released in the immediate area.”

What? Murder the things? No way. Where’s the fun in that?

Source link