No products in the cart.

Outdoor Adventure

Is Blood-Flow Restriction the Future of Performance?

After a workout several years ago, Mikaela Shiffrin slipped inflatable cuffs over her upper arms and legs, then cranked through a 20-minute circuit of relatively easy exercises. “In 15 minutes I was exhausted, more exhausted than I felt from a two-hour strength session,” the two-time Olympic gold medalist says. “I remember thinking, Oh my gosh, my arms are sore, like I just did 200 push-ups or something.”

Exhaustion was the point. The technique—called blood-flow-restriction training, and also known as Kaatsu—uses pressure around the arms and legs to significantly limit circulation, triggering a wide range of adaptations in the body. Invented in 1966 by Yoshiaki Sato, an MD and a researcher, BFR training was first adopted by Japanese bodybuilders and powerlifters. It wasn’t until the early 2000s that it made its way out of Japan, thanks in part to Jim Stray-Gundersen, a physiologist and physician and a former medical adviser to the International Olympic Committee, the International Ski Federation, and NASA. After hearing about BFR training at a medical conference, he traveled to Japan in 2013 to study the technique. It wasn’t long before he’d partnered with Sato to launch Kaatsu in North America. The two split ways, and Stray-Gundersen cofounded his own BFR system, called B Strong.

Since 2010, more than 900 papers have been published on BFR suggesting that pairing it with relatively light resistance training or aerobic activity can lead to a rapid increase in muscle size and strength, oxidative capacity, and tendon density. Its efficiency is the reason BFR has grown in popularity over the past decade for injury rehabilitation, especially following surgery. Now athletes such as Shiffrin and marathoner Galen Rupp are using BFR to move the needle on performance.

You know the feeling you get at the end of a long ski run—that agonizing, aching, almost unbearable leg burn? Imagine that sensation persisting and then building until your muscles fail altogether. That’s BFR training in a nutshell. Limiting blood flow while exercising restricts oxygen delivery to the working muscles while accelerating clearance of metabolic by-products such as lactate. That quickly disrupts homeostasis, the delicate physical and chemical balance within your body, and creates a temporary state of metabolic crisis, sending a strong fatigue signal to the brain that triggers a cascade of hormonal responses, Stray-Gundersen explains. “We elicit these anabolic resources by hoodwinking the body into thinking all sorts of major damage is being done, when in reality it’s a combination of easy exercises and blood-flow restriction,” he says.

For a sport like alpine skiing, which requires considerable strength and endurance, BFR “checks a lot of boxes,” says Jeff Lackie, Shiffrin’s strength and conditioning coach. Because BFR involves relatively modest loads, Lackie and Shiffrin use it in the off-season to safely stack volume during strength-training sessions. Once the race calendar kicks in, they rely on it to maintain her strength level and help with recovery despite a chaotic travel schedule.

There’s a distinct mental component. The overwhelming amount of lactate that builds up in the muscles feels awful—but that’s exactly what Shiffrin experiences at the bottom of a long World Cup run, explains Lackie. By acclimating to the discomfort, she can keep a cool head and stay coordinated through her final turns. “Like anything in life that makes you uncomfortable, there’s a mental side to pushing through that,” Shiffrin says.

While fatigue is key to the method, there are drawbacks. “When people become fatigued, mechanics fall apart,” says Nicole Haas, a physical therapist and the founder of Boulder Physiolab in Colorado. Sloppy form can reinforce bad habits instead of enhancing the brain-body connection, which is an important part of performance. “I worry about injuries happening from just trying to tire yourself out,” she says.

Haas also notes that while studies have demonstrated that BFR can lead to significant improvements in muscle size and VO2 max, it’s not clear that these changes translate into real-world performance gains. In a 2015 study on the effects of supplemental BFR training among experienced cyclists, participants increased VO2 max by an average of 4.5 percent. Yet their 15-kilometer time-trial performance didn’t improve. “There are so many variables when you cross into sports and performance, and that’s the hard part to measure,” Haas says. What’s more, because most clinical studies looking at BFR training last a relatively short period of time, there’s a lot we don’t know about the long-term effects. Could there be a strong response at the onset of training and a plateau later on? And with so much fatigue accumulation, is there risk of overtraining? Then there’s the fact that little agreement exists on how to optimally implement BFR training.

The scientific literature is limited, and it’s only through decades of experience—trial and error with various techniques across numerous sports involving all kinds of athletes—that the bad ideas will get weeded out. For now “it’s an excellent tool in the toolbox,” Lackie says. But it’s only one tool: he and Haas are quick to emphasize that they see BFR as a supplement to, not a replacement for, other training methods.

It’s not a shortcut to performance, either. You still need to put in the work. But BFR lets you safely add volume to your workouts and recover faster, allowing you to fit in more training during a given week. “At the end of the day, the more training you do, as long as you recover from it, the better your performance is going to be,” Stray-Gundersen says.

That first time Shiffrin tried BFR, when her arms felt like lead? She awoke from an afternoon nap fresh enough to push hard again in her evening workout. “Not only was it making each session more effective, but I was recovering really well, maybe even better than before,” she says.

Safety First

Important precautions for adopting blood-flow-resistance training

The kind of cuff you use during unsupervised BFR training is key, says physiologist Jim Stray-Gundersen. He recommends one that’s inflatable (so you can control the pressure) and elastic (to accommodate changes in muscle size during exercise). Just make sure some quantity of blood is flowing into the limb while wearing it. BFR is safe for anyone following accepted protocols, unless you have sickle cell disease or lymphedema, are pregnant, have a fresh wound or a fever, or are in pain due to a healing injury. The following resources will help get you started.

B Strong training systems: These kits come with inflatable arm and leg bands, a hand pump, and an app with video instructions and tutorials. From $289

Kaatsu Specialist Certification Program: An online offering at Kaatsu.org that teaches coaches, therapists, and athletes how to properly administer BFR. $250

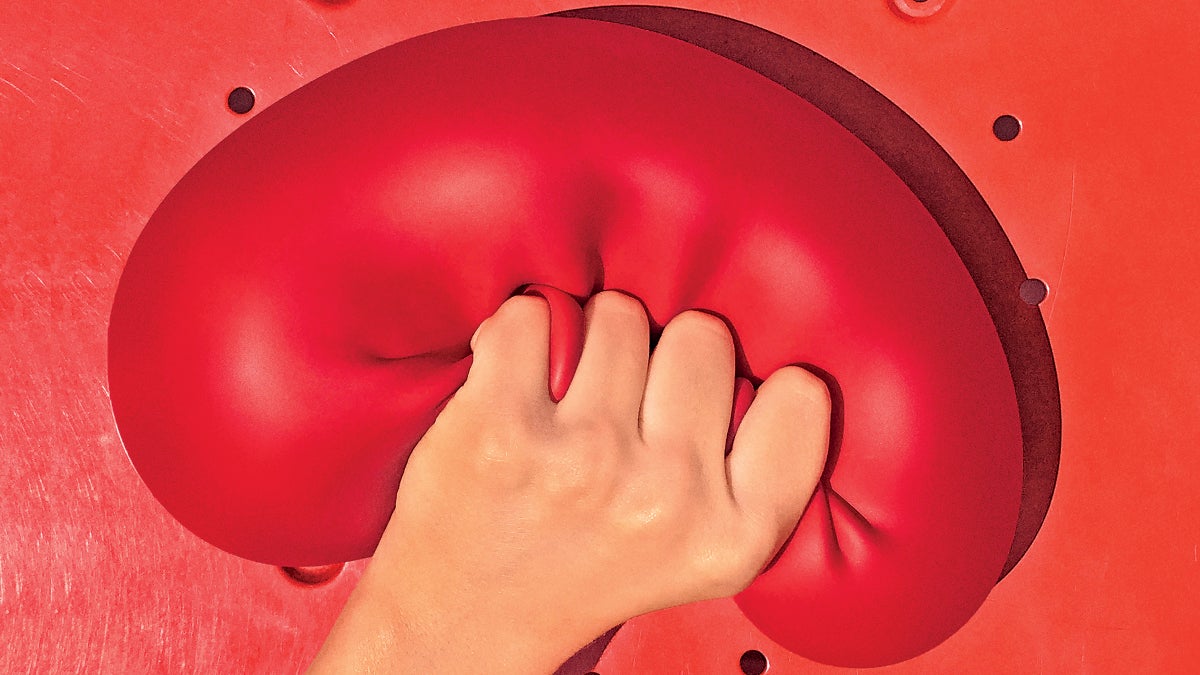

“Basics of Blood-Flow Restriction Training”: Camp 4’s short online course is designed expressly for rock climbers, from strength and conditioning coach Tyler Nelson. $60

“Blood Flow Restriction Exercise: Considerations of Methodology, Application, and Safety”: This research paper, published in the journal Frontiers in Physiology, recommends a set of guidelines for BFR resistance and offers aerobic and preventive training, with notes on how to go about it safely. frontiersin.org

Source link