No products in the cart.

Outdoor Adventure

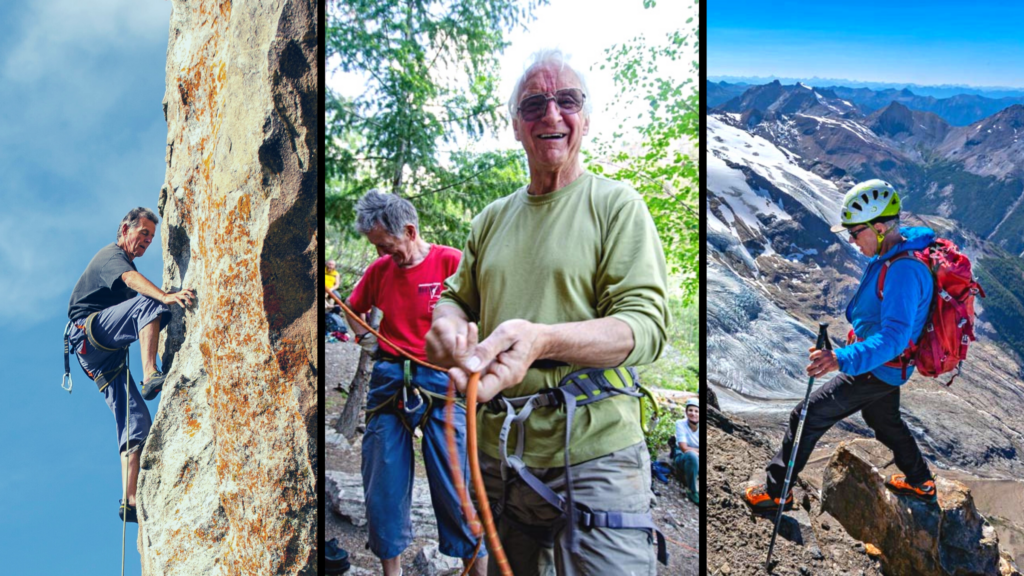

Life Advice from the Oldest Climbers at the Gym

Pat Bates and his climbing buddies stand out at the crag. That’s because Bates and his crew are, well, old: their average age is 71.

Bates, 67, is short and lean, and wears a flat-brim baseball cap over his unruly salt-and-pepper hair. He and his crew—five other senior or near-senior citizens—met in 2015 at the Spirit Rock Climbing Centre in Kimberley, British Columbia, where they now train regularly and belay for the gym’s after-school kids’ programs. They get outside whenever they can, climbing locally and traveling to other North American destinations. Recently, they began developing a crag in the popular St. Mary Lake area just west of Kimberley. They call it Tora Bora, after the adjacent trail, and in three years have created more than a dozen single-pitch routes ranging from 5.8 to 5.10b, with one 5.11—“routes in our pay grade,” says Bates.

I’ve always assumed that rock climbers lose strength and stamina with age. At least I have, at 46. But this crew of grandparents seems to be stepping on the gas. I felt like I had something to learn about pursuing outdoor passions later in life, and they graciously offered their wisdom.

Pat Bates

Pat Bates told me that the sport “is paramount to my being, essentially.” He was born in Kimberley and has been climbing both rock and ice since he was in his early 20s, but his enthusiasm for the sport has ebbed and flowed over the years. And that’s okay, he says. You can put your passion down for years and still maintain your love for it.

He’s delighted to be at a stage in life where he’s climbing again, which he attributes in no small part to his crew of like-minded friends, and the fact that his wife Jocelyn recently picked up the sport.

Bates assures me that sport climbing is great for older people because it doesn’t require massive commitments of time, energy, or equipment. “It’s not like going into the big mountains where it’s big days and it’s super physical,” he says. “Sport climbing’s more casual—you spend more time sitting around in the shade chewing the rag. You can tailor it to your abilities.”

He also tells me that his ego has quieted as he’s gotten older. “We’re just out here having fun,” Bates says. “So what if we climbed two grades harder 15 years ago? This is now.” A sense of humor is also important. Consider the name of the route at Tora Bora that he and Wilkinson set: No Green Bananas (5.8, 11 bolts). “When you reach a certain age, you stop buying green bananas,” Bates explains. “Because you might not be around long enough for them to ripen.”

Debbie Gale, 74

Debbie Gale climbed regularly as a young woman in her 20s, before having two kids with her husband, John, and then started back up again in her early 70s. Debbie credits her crew, which she describes as very encouraging, for reigniting her passion for the sport. She was surprised to discover how hard it was to overcome the cognitive dissonance between climbing as she remembered it, and climbing in a body that’s taken more than 70 laps around the sun. “I haven’t got the balance that I used to, I haven’t got the flexibility, and most of all I haven’t got the strength,” she says.

She quickly realized that while she can improve her physical skills with time and practice, she’ll never be able to move like she did as a 20-year-old, “doing gymnastics on the rock,” as she says. Instead, she began to view the sport as playtime. She’s started sticking to the easier routes, “to just have fun and muck around.” The technique has brought levity and curiosity back into the experience. “If I only get eight feet off the ground, it doesn’t matter to me.” Debbie says.

John Gale, 75

John Gale, who has been climbing since he was 14, doesn’t sugarcoat what it’s like to be an athlete in his eighth decade of life: “You can’t climb as long or hard in a day. You have to rest. You get more aches and pains. The aches and pains last longer.” He works with a physical therapist to maximize his mobility, and says his fingers and shoulders are especially vulnerable these days.

Gale serves as his crew’s resource on injuries and prevention, a topic of interest he shares with his and Debbie’s 40-year-old daughter, who climbs at the 5.13/14 level, and who he calls “a mine of information.” Their son is also an accomplished athlete, and while Gale enjoys watching his kids “glide up almost effortlessly,” he prefers climbing with his peers. “With the kids, it always feels as though I’m slowing them down quite a bit,” he says. “I’d rather be with the old guys, where we all know exactly how each of us is feeling when we say we’ve had enough.”

Ken Wilkinson, 81

Ken Wilkinson appreciates the sport even more now that he’s retired because, “Every day can be a climbing day.” He’s a late-comer to the sport, having taken it up in his early 60s at the urging of his youngest son, Kevin who needed a belay partner. Kevin eventually became a professional athlete with the Petzl team, and the two would sport climb together all over the world. They were at Maple Canyon, near Salt Lake City, when Kevin notched his first 5.14, and Ken his first 5.12.

His style hasn’t changed his 80s, Wilkinson says. “I’m an overhang, juggy guy,” he says. “That’s how I was brought up at [local climbing area] Lakit, which is steep but has big holds. I’m not very good on slabs; I don’t know if my ankles are not flexible, or what, but I’ve never trusted my feet on slabs.”

For Wilkinson, the sport’s biggest impact on his life has been the relationships and connections it his fostered, first with his son and now with his friends. His life advice? “Find something that you love to do, and you will do it for life.”

Bruce Hart, 64

Bruce Hart didn’t think he should comment for this story. “My co-climbers are much more accomplished than I am myself,” he says. “And I’m 64, so technically, I’m not even a senior.” But his cohort insisted. Hart took up the sport about four years ago, after double hip replacement surgery.

“I needed to rehabilitate my hip,” Hart says, “and the climbing gym is really friendly for working on that kind of thing—your strength and flexibility, your balance.” He’s since progressed to cragging outside with the crew, and recently set his first route at Tora Bora, a 5.8 he calls Lichen It.

Hart is less reckless and more thoughtful about preserving his body’s mobility that he used to be. “When you’ve got two bum hips, it’s not like there’s a 50-50 chance of landing on the good one,” he says. Hart hopes that by being calculated, he, like Kenny, will still be able to participate in his 80s.

While he’s still relatively new to the crew, Hart already holds these friendships in high regard. “You know those college friendships where you can just pick up the conversation right where you left off the last time, even if it was a decade ago?” he says. “I think your climbing pals become like your college pals. You go through a lot together.”

Source link