No products in the cart.

Outdoor Adventure

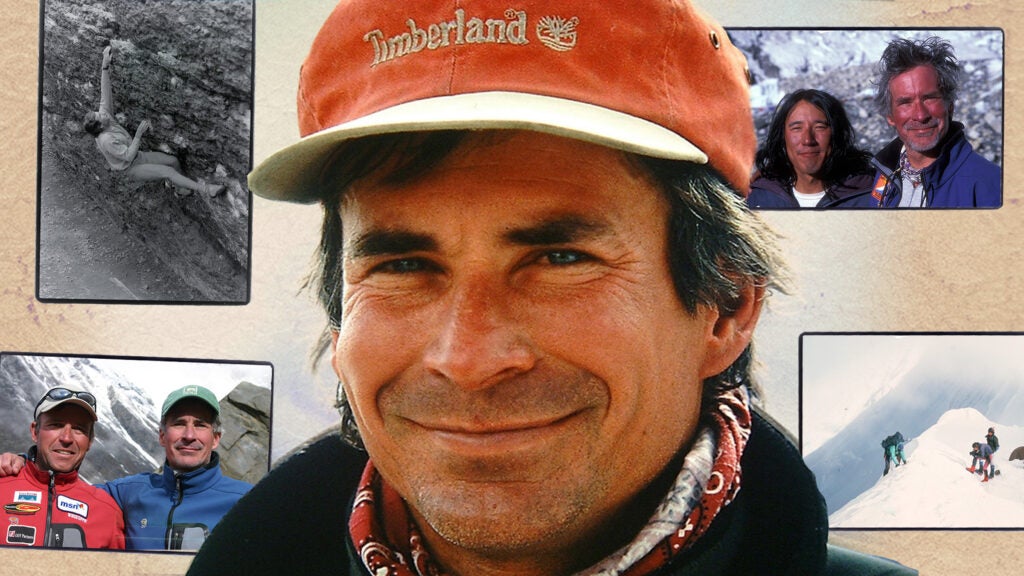

Loved Ones Pay Tribute to Everest Filmmaker David Breashears

Outdoor enthusiasts lost a master of adventure storytelling earlier this month, when David Breashears died at age 68 at his home in Marblehead, Massachusetts. Breashears was a pioneer of filmmaking in the high mountains, and his documentaries about Mount Everest and the Himalayas brought millions of viewers up close to the famed peaks. His 1998 film, Everest, was the first to capture the world’s highest peak in ultra high-definition IMAX. And his 2008 film Storm Over Everest, which was produced by Frontline, took viewers inside the deadly 1996 disaster on Mount Everest.

Breashears touched the lives of many through his work and his expeditions, and after his passing we compiled an outpouring of stories and memories from those who knew him best. Some of these tributes came from fellow mountaineers: Ed Viesturs, Sue Giller, Jimmy Chin, Ang Phula Sherpa, and others. Some came from rock climbers who watched Breashers excel on challenging routes in the seventies and eighties. Still other memories came from Breashears’ friends and family back home. Below, we have published these memories and photographs in full, to give you a sense of the man behind the many hard ascents, and the camera he hauled up high peaks.

He Set the Bar to 11

David Breashears was both a great friend as well as mentor. Early in my climbing career, in the late seventies and early eighties, as I read about mountaineering history and the current stars, I became aware of David. I admired him from afar and took note of his skills as a climber as well as his talent as cameraman and filmmaker. In 1987 we met coincidentally for the first time in the windswept, desolate Tibetan village of Xegar. We were both on our way to the north side of Everest. David to do some film work, while loosely attached to a Norwegian team, and me on my very first Himalayan expedition as part of a small American team led by Eric Simonson.

Years later, in 1996, after I had by then been to Everest seven times, David invited me to lead the Everest IMAX filming expedition. He would be focused on being the lead cameraman and director of the film. It was a monumental task, which in my opinion, not many people were capable of, nor had the skill set to achieve. Those were the types of challenges that David embraced and excelled at accomplishing. It was during that project that I witnessed his amazing work ethic, meticulous attention to detail, and his striving for perfection. He said to me “If my name is associated with something, it has to be done right.” His leadership inspired me and elevated me to go to another level. The IMAX expedition was the single-most challenging expedition of my career. I thanked him for including me on that journey. We partnered again on Everest for two other film projects in 1997 and 2004, standing together twice again on Everest’s summit.

Coming full circle, after having met him on my very first Himalayan expedition in 1987, he made an effort to join me in 2005, 18 years later, at Annapurna base camp, just days before I climbed to the summit—my last of the 14 8,000-meter peaks. We had a spell of bad weather, and before we made our final ascent, David had to leave for home. He asked us to keep him informed via sattelite phone as we made our way up. Veikka Gustafsson (my climbing partner of ten years) and I finally made our push. Climbing alpine style, we arrived at our second and highest camp, within two days, hoping to go for the summit on the third day. There we got trapped by a windstorm which held us there for two full days. Not wanting to descend, but not knowing how long we could hold out, we were truly tested. I chatted with David from this battered camp, on the sat phone during this time, and he encouraged us to hang in there and be patient. His positivity, along with the strength of my wife, family and friends, gave me the strength to wait it out. His presence was powerful.

He was always a man that I looked up to and I strove to emulate his level of attention to detail and planning. He set the bar to 11. He will be missed. —Ed Viesturs, American mountaineer

He Gave Me My First Big Break

I very much tried to follow in the footsteps of David, and in a way he gave me my very first break in the industry. Conrad Anker and Rick Ridgeway were leading a National Geographic expedition to the Chang Tang Plateau, and I filled in for David’s after he had to leave the expedition due to other obligations. I was very new. Rick told me to just commit to the shot and figure it out, and he mentored me on that trip. After that trip, David spoke with Rick and Conrad about how things went, and he then reached out to me. He needed someone to film on Everest in 2004 and apparently I had gotten favorable reviews. David brought me on the trip and it had a huge impact on me.

I got to see how David ran a large-scale Everest production, and how he approached filming in the mountains and climbing high peaks with a production crew. It was invaluable because I got to see how it was done correctly, and it accelerated my own growth as a filmmaker in the mountains. I saw how every detail counts: the gear, team, timing. I also saw how, with David, there was focus when there needed to be focus, but he was also a real jokester who made time for fun. He took me under his wing and I feel incredibly fortunate. And I’ve tried hard to live up to those expectations and standards. Because he pushed me to work harder and go farther than I would have on my own. —Jimmy Chin, American mountaineer and filmmaker

The Kloeberdanz Kid

I first knew Dave as the skinny young Kloeberdanz Kid from his Boulder days in the seventies. But I really came to know him better on our shared Himalayan expeditions: 1981 East Face of Everest and 1986 North Ridge Everest via Tibet. He was just learning his filming craft on the 1981 trip, where he was supposed to be the sound gaffer for Kurt Diemberger. But Dave was the only member of the film crew who could do the technical climbing, and thus became the camera operator too. On the 1986 expedition, Dave was running the whole show (producing and filming). While Dave could be extremely focused on his work, he always took time to be very supportive of me in my climbing career. He was a caring person. I always looked forward to catching up with his life at American Alpine Club meetings. Alas, that is no longer an option. —Sue Giller, American climber

His Social Work Will Remain Immortal

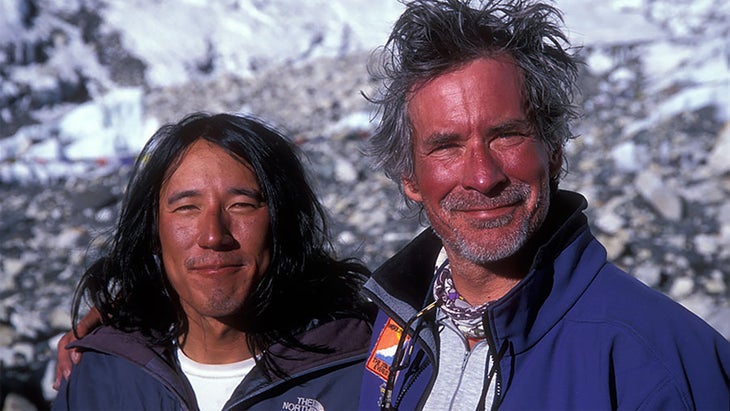

In October 1998 I had the opportunity to meet David Breashears at the house of my uncle, Wongchhu Sherpa, in Kathmandu. I was probably ten years old at the time. David and my uncle were very close friends, and I felt that the relationship between them was like brothers. David’s work in tourism and expeditions were done through my uncle’s company. In the year 2000 I started working as a porter on treks operated by David, and in the following years I got to work various roles in Everest expeditions, eventually attaining the job of climbing sherpa. For my first climb up Everest I had the opportunity to climb with David, and I had the opportunity to learn mountain climbing, photography, and filmmaking from him. I got the opportunity to work together on 44 different projects, and I worked with David 1,251 combined days over the years. He used to treat me like his son and give me inspiration by teaching me my work.

In 2015 the great earthquake hit Nepal, and on that day David and I were climbing Mount Everest. We had moved from Base Camp and reached Camp 1. We were in no position to do anything but watch helplessly and save our own lives. After that incident, David was traumatized from the inside, and began to worry about what can be done. One day he told me he wanted to stop climbing and study the effects of climate change on the mountains, and do work associated with it.

David has always been providing financial benefits to Nepalis through various means, and his social work will always remain immortal. When he came to Nepal, he did lots of work in my village, Tapting, in Solu Khumbu. In collaboration with my uncle, he helped in healthcare, education, hydropower, drinking water, and other public works.

In my 18 years working with David I had the opportunity to get to now the world. Sometimes we laughed together, sometimes we cried together, and sometimes we rejoiced together, and sometimes we were scared together. By loving me like his own son, I have given him the position of a religious father. Because of that I got a chance to act in his Everest movie and even step on the red carpet at a Hollywood premier. I am probably the first Nepali to walk on the Hollywood red carpet! —Ang Phula Sherpa, Nepali mountaineer and guide

A Brother I’ll Always Remember

Being the youngest of four siblings, only two years apart, David and I were a close pair growing up. His personality, marked by tenacity, determination, and a love of nature, was evident from a young age. I remember watching him tie hundreds of knots for his Boy Scouts certificate, which I was assigned to supervise by our mom. Once he set his mind to executing a task, there was no stopping him. When something piqued his interest he would learn everything he could about it, and often he’d rattle all the facts off to me.

Climbing was his ultimate goal, and once he discovered that passion he was set on doing it every second he could. In high school he dropped our mom off at work every day with the assumption that he’d take her car to class, but instead he would head straight to Boulder to climb all day before using a drill to reverse the mileage on the car and returning to Denver.

David was prepared enough for Everest by the time he climbed it that my biggest fear was him sleepwalking off a cliff. He sleepwalked enough as a child that when we went to summer camp I tied our wrists together with string when we went to sleep in our tent (and though he was still there in the morning, the string had mysteriously been untied). When I told him about my concern he just laughed and told me that wouldn’t happen. I wasn’t worried about the rest because David had prepared so carefully and intentionally for the climb, as he always did.

David valued the community he built around mountaineering as much as any other aspect of the climb. He built so many lasting friendships on unwavering trust and a commitment to keeping each other safe in dangerous conditions. He also respected nature and was deeply concerned about the fate of our planet. He was as passionate about the climate crisis as he was about anything else, founding GlacierWorks in 2007 dedicated to raising awareness about climate change. Though he is primarily remembered for mountaineering and filming, I know he would want his legacy to be this activism.

I’ll miss my brother’s voice saying “Hey sister” when he picked up the phone, and hearing all about his latest interests. This will be the first year without a dozen roses from David on Valentine’s Day, plus a dozen more on my birthday and the inevitable comment that, for the next two months, we were just a year apart.—Lisa Breashears, younger sister

My Unofficial Uncle

I’ve known David my entire life—he was the unofficial uncle in my family, and had known my mom since she was in her twenties. By the time I came around he was a big figure in our family, and an extremely close friend. He’d come over for dinners, sometimes appearing out of thin air in an unplanned way. He’d come back from an Everest expedition, sit in our living room, and tell his stories in such a way that captivated everyone. There was a sense of mystery about him.

So when I was 12 David was putting together an expedition to Killimajaro, and lo and behold he wanted to have a female child to participate. He approached my parents about me going and spoke to me about it. We had traveled before but never done a multi-day expedition to high altitude. My father came along on the trip and it was challenging because we were filming with IMAX cameras. He was directing so many people and in charge of everything, but he still found a way to have that uncle feeling with me. He made me feel safe and protected and encouraged me every day.

One day, we were heading up the mountain and I was having a hard time because my feet were so cold. David could see that I was uncomfortable and embarrassed. He stopped everyone on the trail, told me to take off my backpack and boots, and then proceeded to place my bare feet up under his jacket onto his warm bare stomach. It worked. It didn’t matter that we were chasing the sun for the perfect shot that day. In that moment, taking care of me mattered most. —Nicole Wineland-Thomson, neighbor and family friend

A Colleague, Close Friend, and Neighbor

David appeared at my office doorway one day and in a way never left. He wanted to talk about Tibet. On a recent trip to Lhasa he’d secretly interviewed, on video, young Tibetan activists, wanting to fight the Chinese occupation. Not only that, he’d ridden his bicycle into the countryside, scaled a nearby mountain and filmed the prison camp. What could he do with his footage? We went to lunch.

He would become a colleague, a close friend, and our neighbor round the corner. He was a great companion, curious and opinionated. Fearless and precise. He calculated risks and took action. That’s how I found myself in the back of a truck, climbing a 17,000 foot pass from Nepal into Tibet with David and my friend the journalist Orville Schell, posing as tourists with a home video camera, trying to take the measure of the Chinese occupation. Orville and I were completely dependent on David’s judgment and decisions for the next ten days; maneuvering into monasteries, meeting monks who were contemplating taking up the gun, and finally making it out by air from Lhasa. The film went out on Frontline, and our lives were linked.

One day in the mid-90s I was talking to Greg McGillivray in Laguna Beach, after we’d finished some editing work together. He said in passing he wanted to make a film about Everest. I told him I thought the one person who could get an IMAX camera to the summit was David Breashears. He’d never heard of him, but wanted his phone number. I asked David to take his call. The IMAX film made history, in part because of the awful conjunction of a deadly storm and a crowded mountain, but also that David, after saving lives and sharing supplies, rallied his team and delivered on what he’d promised to do: put the camera on the summit.

David was proud of the film, but didn’t think the IMAX format gave enough time to the complicated tragedy and its human failings. Using his own money he traveled around the world and interviewed as many key survivors as he could, fellow climbers who opened up to him. It was typical David: obsessive and daring, financing his own convictions, convinced that he could get a film made somehow. He took the upfront risk and it paid off: it was broadcast on Frontline — “Storm over Everest” — I think the best account of the tragedy.

At home in Marblehead, David would appear on our porch, discuss menus and argue the particulars. He was part of our family. We’d go fishing for striped bass and I’d drop over to watch him lay out piles of gear and cameras, meticulously from room to room, planning the next expedition and the logistics of what would pack where and what belonged with yak or Sherpa.

In 2008 our Frontline team asked him to go to “The Third Pole”—Everest—for a film about global warming. The producer Martin Smith drove with him to the base of the Rongbuk Glacier on the north side. Marty told me how David politely but firmly suggested that he and a Sherpa would move more quickly without him. They rolled up their pants, forded an icy river and took off. David had identified the actual spur where George Mallory had taken an iconic photograph of the glacier and the mountain in 1921. David framed an exact replica of the image, in order to dissolve one over the other, showing the massive loss of ice over the past century.

He later said that sequence in the film was an inspiration for GlacierWorks, the collection of massive photographs he made across the Himalayas to call attention to global warming. They represent a series of expeditions that were once again David taking the financial risk, convinced that his work was important and would be a contribution to the world. Today, an exhibition of those photographs, called COAL+ICE, is at the Asia Society in New York. It’s been on show around the world since 2011.

Setting off on the first of those expeditions, he told me not to worry. It would just be David, two sherpas, and a couple of yak herders.

I like to think he’s there now, in his beloved mountains. —David Fanning, founder and executive producer (1983-2015) of Frontline

He Supported Sherpa Families

I am very sad at David’s untimely passing. We will miss him so deeply. His legacy, friendship, mentorship will be forever remembered. He was my boss, friend, mentor. I met David the first time in 1996 at Everest base camp while he was leading the Everest IMAX Expedition. I came to know him through my brother in-law Jangbu Sherpa (who carried the Everest IMAX camera to the top of Mount Everest). In 1997 I worked as a Base Camp kitchen boy for his Storm Over Everest expedition.

During my early climbing career in 2004 I got opportunities to work with his filming expeditions, and I summited Mount Everest for the first time with him and his team. Afterward David gave me other opportunities to work with his GlacierWorks photographic expedition as head photographic assistant for many years in Nepal, Tibet, China, and the Karakoram in Pakistan until 2012, when I was employed by Peak Promotion in Nepal. I was so grateful to work with him for a great cause. During the many expeditions he always talked about our families and future.

David was so influential in my life. He was always worried about me and our families’ future in Nepal because of political instability. He often told me to have our kids focus on math, science, and English at school. I told my kids the same words that David said. Over time my son graduated in mechanical engineering in the United States. David and another good friend, Dick Morse, invited me to visit the United States multiple times.

By 2012 I climbed Everest four times and survived multiple close calls in the mountains. Over the years I became a permanent resident in the United States. I was able to bring my family for a better education/future for my kids. David supported me and many other sherpas families’ for better futures. I will be forever grateful to him. —Mingmar Sherpa, Nepali mountaineer and guide

Most of Us Struggled to Keep Up

David always reminded me of a whippet—lean and fast and moving at a pace most of us struggled to keep up with. His mind moved as quickly as his body, and he was always chasing down something in books or conversation he wanted to understand. He set the bar high—for himself and everyone around him—and whether developing a new filming technique at altitude, finding the perfect words or images to tell a story, or mastering a new pasta recipe, David was an indefatigable force of nature in all things he took on.

David is well recognized for his remarkable accomplishments as a climber, filmmaker, author, and climate activist. But he was also an extraordinarily kind and generous human being and a friend to many. My family was deeply moved but not surprised that David jumped on a train in Germany, grabbed a flight from Paris, and drove through the night from Boston to make sure he could be with my husband (and David’s partner in Arcturus Motion Pictures), Andy, one of his closest friends, in Andy’s final hours. You can be sure there are many families in Nepal who have stories of their own to tell about the decades of friendship they shared with David.

As in life, David moved on quickly, too early and too soon. We were lucky to have shared some of his magic. —Kathy Harvard, vice president of Inner Asia Rugs

The Story of Perilous Journey

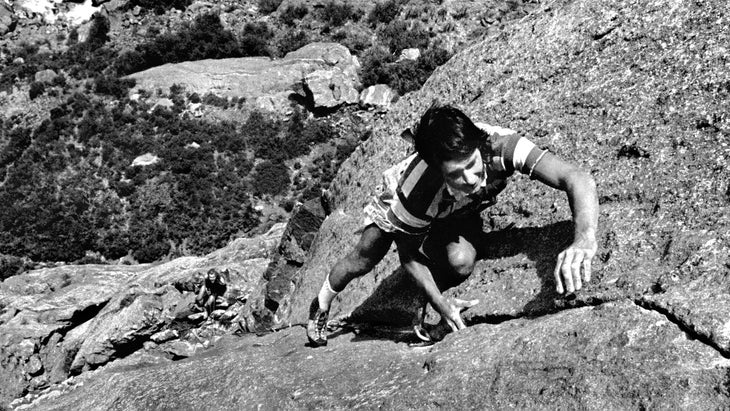

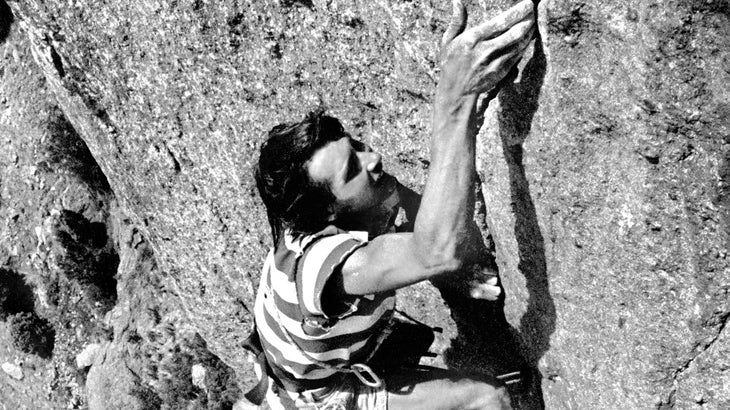

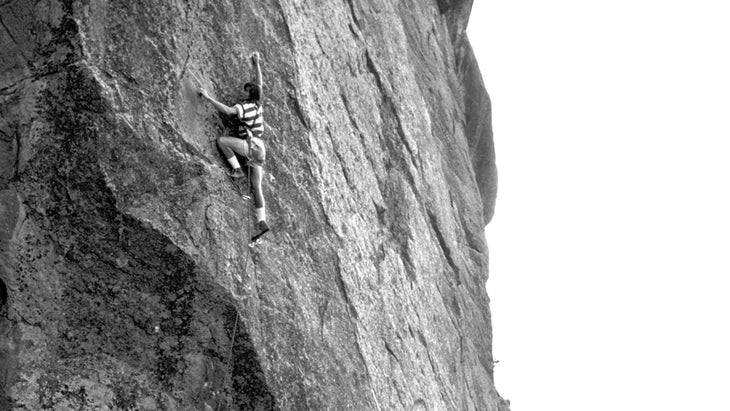

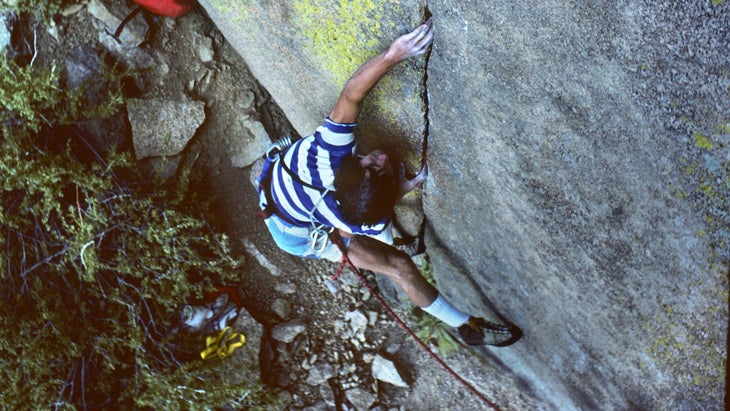

Climbing with David Breashears in the early to mid-seventies was a great time of adventure and camaraderie. We considered ourselves a climbing team, as our chemistry worked well together. By the summer of 1975 Dave was 19 and ready to make his

mark on the climbing world. We had been eyeing a blank face on a cliff above Eldorado Canyon called Mickey Mouse. Dave’s intent was to try the blankest route up that face. We climbed in the style of the times, which was ground-up ascents with no bolts. We were disciples of the clean-climbing movement. Hiking up that morning I had no idea something truly amazing was going to happen that day.

We got to the wall and started bouldering up the route a ways. At some point we decided this is it and roped up. We traded attempts and realized there would be no reversing the first crux. Dave made it past the first crux with no protection available. Standing precariously on a sloping foothold, he was calm and in control as he looked up at what lay ahead of him. Both hands dropped to his side as he shook them out and yelled down to ask me which way looked good. I yelled back, “The left looks promising!”

In my mind all I can see, still, is the second crux. It looked more difficult than the first. At this point Dave was 40 feet up, the second crux at 50 feet.

Dave started up a few moves on poor holds and unobvious moves. He peered up and out and downclimbed back to the rest. I offered encouragement, saying “You look solid, you got this.” I knew he was going up, not down. He tried it again, but backed down to the rest.

He looked down at me and said, “I’m going this time.”

“You’ve got this!”

I had 100 percent confidence in Dave. After a quick shake out he went at it again; having figured the sequence out, he looked solid on it. He pushed through the second crux, running the rope out to the belay. He did the whole route, something like 100 feet, without pro.

Once set up, he called, “On belay” and, “Don’t fall, we want a clean ascent.” He always considered it a team effort but I knew the genius was in his mastery of the route. I was really sketchy on the moves but able to finish without a fall, and upon reaching Dave told him what an incredible piece of climbing he had just accomplished. I knew what I had witnessed. I believe the route, called “Perilous Journey,” changed everything for Dave. He took climbing a step into the future that day, a future where all things were possible for him. —Steve Mammen, American climber

The Master of Control

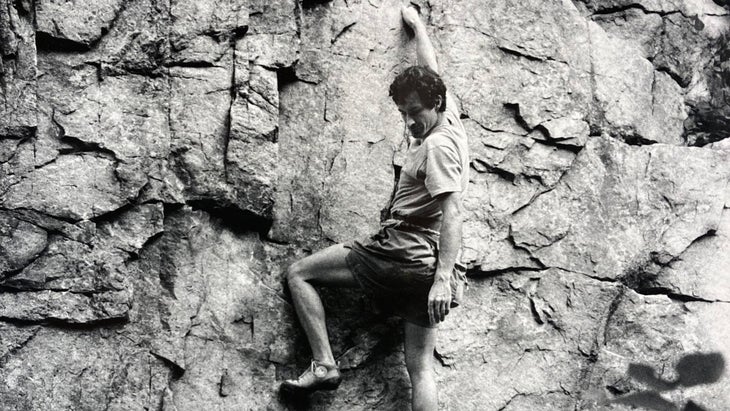

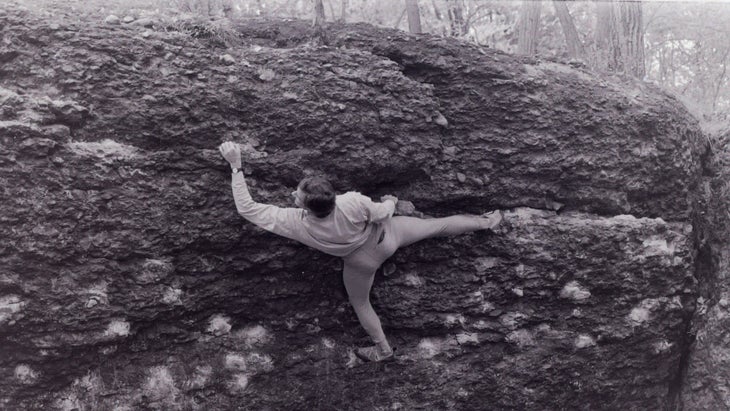

I met Dave back in the seventies, when I was in high school. Much of my climbing at the time was bouldering at Horsetooth Reservoir outside Fort Collins, Colorado, and roped climbing in Eldorado Canyon. One of my main partners was Steve Mammen from Denver, and I met Dave through him. Both Steve and Dave were a couple years my senior and both were in their climbing primes. Dave would frequently come up to boulder at Horsetooth, and he was gracious enough to let me tag along.

Climbing during this time was vastly different than much of climbing today. Being in control was key. Falling was usually not an option but a last resort. The ability to escape from a situation both in rock climbing and high bouldering, and the art of down climbing, were essential. Gear was much less sophisticated as well: nuts were just coming onto the market, and there were no camming devices; there were also very few harness options. Most climbers opted for a “Swami Belt,” a length of two-inch nylon webbing wrapped around the waist and finished with a water knot. There was incentive enough not to fall. There were no bouldering pads. High boulder problems required the same control and ability to escape as rock climbs did. Footwear was another huge difference. Sticky rubber was still years down the road. Shoes at the time were stiff, with hard rubber. Precise footwork was critical and required full awareness of placement.

It was with this gear and in this style of climbing that Dave excelled. He was a master of down climbing and climbing in control. He would spend hours going up and down sections, gaining the confidence to finally push through. He had laser accuracy with his Vasque Ascender boots, the “Shoenards.” He rarely, if ever, fell.

I ran into Dave a number of times later in life. He was always smiling, asking about his friend Steve and wanting to make plans to go bouldering together. I was very lucky to be able to spend time with Dave, a true master and legend, on the rocks. —Mark Wilford, American climber

He Adopted Us

David came into our lives in his teens. He found my wife, Pamela, and me amongst the tribe of seventies climbers in Eldorado Springs Canyon. We were five years older, in possession of an Eldo shack and a dog, and we adopted David, except that he adopted us.

Our friendship endured for 52 years, enough time to feel certain of who he was. David’s wry, discerning smile, rock-solid loyalty to friends, and somber intensity accompanied us around the world. There he was, quietly observing the lunacy of guiding David Lee Roth up Lobuje in Nepal, diligently filming the excavation of Incan sacrificial mummies in Peru, tearing up as we guided a group of mentally disabled teens up Kilimanjaro.

David was complex: he embodied emotional range from giddy and goofy to dark and brooding. All those many facets were bound together by an abiding love for the natural world, deep empathy for others, and the capacity for rich, meaningful friendships. We loved David and will now depend upon the memories of shared time together. —Mike Weis, American climber and filmmaker

A Passion for Literature and Learning

In 1983 David Breashears, Kim Momb, and I were the youngsters on a star-studded American expedition attempting to make the first ascent of the east face of Mount Everest. I had followed a more traditional academic path and was on leave from medical school. David and Kim were full-time climbers since high school.

As a young rock fanatic in the seventies I had been, of course, aware of David Breashears. His bold ascents in Eldorado Canyon were legendary. I looked forward to hanging out with David and talking about climbing. However, he just wanted to discuss books. He chided and derided me for wasting time and money on an Ivy League education. His expedition duffle was heavy with issues of The New Yorker and books by Carl Sagan, Richard Feynmann, Camus, and Kant. He had a small notepad for writing down every word he did not know. David looked each one up in a dictionary and inserted that word into several sentences over the next few days. Over time he became my most articulate and best-educated climbing partner.

David was always full immersion and all in. He moved to Boston while I was still in medical school. We became frequent climbing partners. What I savor, looking back, were the conversations around the dinner table or in the car driving to New Hampshire much more than climbing the Black Dike on Cannon Cliff in full conditions.

When David began his work in film, he read constantly and studied every angle of the art. He was the ultimate craftsman, pushing himself to be his very best in every pursuit. When I moved to Utah, he came out a few weeks every year to ski with me and spend time with his friend Dick Bass. Each visit he was mastering something new, from glaciers and water geology to molecular gastronomy. He became a great chef and delighted in cooking meals at our home and teaching my daughters the tricks to making perfect homemade pasta.

David Breashears was a groundbreaking climber and cinematographer, a chronicler of the recession of Himalayan glaciers, a superb lecturer inspiring both youth and corporations; but most important, a friend to many and a man who lived a life with intensity and passion. —Dr. Geoff Tabin, co-founder and chair, the Himalayan Cataract Project

The Coolest Uncle

I’ve often thought about how excited other people—like Outside’s readership—would be to have David as an uncle, and that his penchant for adventure was wasted on me, an indoor type of girl. He once offered to climb Mount Kilimanjaro with me, and I asked (as a joke… kind of) if there was a book about it I could just read instead. Still, David applied his adventurous intensity to everything, so I got to see it throughout my life.

I first realized he was a big deal at the premiere of the Everest documentary, when I was three. David introduced the film and pointed us out in the crowd. I remember holding my breath during the scene where he made his way slowly over a chasm on a shaky metal ladder, it was the most frightening thing I’d ever seen.

He was a well of information about all things outdoors. After years of packing as light as possible he could pick up anything and tell you its exact weight, something I made him do incessantly over Christmas when he stayed with us in Denver. Though I spend most my time in archives and libraries now, thanks to David I know how to increase my chances of surviving an avalanche, how to stay alive in the face of hypothermic exposure, and how to prepare for impaired thinking from oxygen deficiency. He told me I couldn’t be scared, that fear distorted the mind’s ability to make good decisions, and the best way to combat fear was preparation. I couldn’t believe he hadn’t been scared walking across that ladder on Everest.

Since he couldn’t get me out on the mountain, David settled for launching an expedition on my terms. The year I planned to apply to PhD programs, David suggested I drive down to Massachusetts, and we’d visit some campuses on my list. By the time I arrived he was well-prepared: he knew the size of the school, the cost of living, and a myriad of other details. That was one of the most fun things about him, if he knew you were interested in something, he’d make a point to obsess along with you. After our trek he made me scallops and we discussed what I liked, what I didn’t, and what other factors I might need to consider. That was David about everything he encountered: he was intense, passionate, analytical, practical, and ready to get things done. I showed him Chef’s Table that evening since cooking was another of his passions. He toggled between talking about the documentary style and the chefs’ approaches to food. He texted me later to tell me he binged the whole show.

That same trip, David took me out on Marblehead’s Bay in a little boat, talking the whole time about how the boat worked, his safety concerns, how to read the compass, what to do in foggy weather or choppy waters. I just wanted to get in the ocean. We were out by a red bobbing buoy that evoked the opening scene of Jaws, which terrified both David and my mom when they saw it as kids. Once I jumped in David wanted me back on the boat almost immediately. I was too excited about my chance to be in the ocean, though, so I stayed.

“Ok Caroline, you have to come in now, your mom would kill me if a shark got you,” he said after a while.

“You climbed Everest, I can’t believe you’re scared of your little sister!” I teased.

Later, I realized I hadn’t been afraid because I was with David, who was exactly the person you’d want by your side at the first sign of danger. He respected nature and he knew it was far more powerful than him. Preparedness and knowledge made David very nearly fearless, with the small exception of those forces he stood no chance against, like the shark from Jaws and little sisters. —Caroline Johnston, niece

Bouldering in Boston

The first time I met David I almost felt sorry for him. It was fall of 1985, and the little bouldering area of the Alcove, a 12- or 15-foot protrusion outside of Boston, was busy. People were bedecked in a riot of Lycra, and he walked up amid the movement and commotion wearing a polo shirt, jeans, and a quizzical smile. Maybe he was a newbie, I thought; the scene might be intimidating. I tried to smile kindly. I had just moved to the area, and it was my first time at the Alcove.

Boom! Pinch grips on the cobbles of the dark, steep conglomerate. Powerful but smooth, static cranks from pocket to pocket, as we others dynoed and splatted. My friend said quietly, “I think that’s Dave Breashears.”

David was there with his dear friend and neighbor Jeff Brewer, and meeting them was one of the best things that happened in my time in Boston. I often bouldered with them and our mutual friend Dave Rose. David was often away in the Himalaya, but he’d come back and start rock climbing again. He is known to the greater world for his mountaineering, from what I think of as “Everest everything” to the huge hard ice face up Kwangde Lho, and to climbers as a superb technical talent. The hard and committing Perilous Journey and Krystal Klyr, famed 5.11s in Eldorado, near Boulder. The Breashears Crack, 5.12, on Cynical Pinnacle, the South Platte.

I thought of David as accomplished, artistic, and technologically expert (“expert” surely doesn’t touch it), but also principled and strict with himself. He stopped his own filming and offered help and all his resources immediately during the Everest 1996 tragedy because it was the right thing. On expeditions his motto was attention to detail.

We last spoke two years ago, when I called for an article on Sibleyville, the classic climber compound in Boulder where he had been taken in as a teen, and which had just burned down in the Marshall Fire. David (Jeff Brewer always called his pal The Great Man, though without letting on) was always busy, but he ruminated at length about how welcoming Paul Sibley and cohorts had been to him as a kid—“The Kid.”

We’d both left Boston long ago, and it was a nice day here in Western Colorado and at his place in Marblehead. He sat out on his deck, looking at the water, and I went upstairs from my basement office to, well, a parking lot, but in spring sunshine. We talked about his non-profit GlacierWorks project, to bring science, art, and mountaineering to the battle against climate change. In 2018, I’d seen his presentation at Telluride MountainFilm, on comparative studies of glaciers over the years. He showed archival photos, “wiping” them over with his, made with systems that created amazing details—he zoomed in on just one rock. David had the skill and meticulousness to use such equipment, and the mountain experience to ascend thousands of feet and set up a camera in exactly the right place. He educated so many, and still had so much to do. —Alison Osius, senior editor Outside and former editor Rock and Ice

Wet and Cold, No Problem

David was wet and cold, yet enthusiastic. His back to the relentless wind, in single-digit temperatures, he regarded the vista before him. Not the mountains surrounding Everest, but duck decoys rocking in the icy Connecticut River of New Hampshire, maybe 500 feet above sea level.

He didn’t leave in the predawn darkness to hike into the ether. He instead rode in a boat to a lonely cove where a blind was built in hopes of luring ducks in the early gray dawn. It was a new experience for David, and he reveled in it. That the prey was “dabbling” ducks was ironic. David didn’t dabble at anything.

When he first joined Andy Harvard and me for our traditional Thanksgiving hunts, David was a newbie. That lasted almost through his first sip of coffee. His amazing grasp of nuance and his fussiness about mastering every detail made him a contributor before the boat even hit the water. Hours later, as the sky brightened, David smiled at the morning and thought of new hunts to come. Too soon it was sunset. —Jason Densmore, former member of the U.S. Nordic Combined team

The Order of the Snow Leopard

David’s high standards in everything extended to his loyalty to his friends, present and gone. In our meetings and events for the Galen and Barbara Rowell Fund for Tibet and other shared activities, David generously contributed his expertise in our planet, its peoples, and its highest mountains as a Tibetan activist and to honor Galen and Barbara Rowell.

When he heard I was going to the Pamirs and Tien Shan, where he had become one of the first Americans to attain the Order of the Snow Leopard, he called to tell me, “Bob, you should start taking one St. Joseph’s baby aspirin [a day] a week before you go. It will help keep your blood thin to protect you from altitude sickness.” It was proactive caring for a friend going to 7,000 meters for the first time. —Bob Palais, American climber and Tibet activist, advisory board member on the Rowell Fund/International Campaign for Tibet

The Warmth Inside

I always thought about my uncle’s photos, films and images as artwork. His focus, attention and energy brought life to a cold mountain that came with baggage, history and weight. The mountain holds so many dualities—life and death, triumph and despair, beauty and detritus. A suitable subject for a long artistic obsession.

In my twenties I moved around a lot, grabbing chances to make artwork and learn from mentors while I worked day jobs. But then my uncle changed my trajectory—my most formative experience happened in Paris at a traditional atelier. An experience sponsored by my uncle, who knew someone who knew someone who had worked at Michael Woolworth Publications. I got to know what it was to think about art every day and couldn’t imagine living another way. It changed my life and I suddenly had my own mountain to climb (cheesy? long artistic obsession).

I got to guide my uncle up a mountain, a hill, one time. We ascended Turtle Hill in the Inner Sunset neighborhood of San Francisco in 2017. The ascent took all but ten minutes. I don’t remember what we talked about, if anything, but I remember that he loved it. “Wow!”—seeing from the bay to the Pacific, spotting the neighborhoods, admiring our shared view. Later that night, shivering from the drastic change in temperature, I asked for tips to avoid focusing on how cold I felt. “Well, just your skin feels cold, the inside of you is still very warm. Focus on the warmth there.” Thanks uncle. It’s that focus on warmth that makes me able to climb. (Again the cheesy pun). —Annie May Johnston, niece

The Best Storyteller

How do I ever begin my words about my dearest David? He was my sweet, funny, deep, illuminating and cheeriest friend. The hole that he has left in my heart and soul is vast. Our journey together has been quite epic! Thank you for being the best storyteller on the planet, for making me laugh just because you wanted to hear my silly giggle, for reminiscing about the now old world camera equipment: the Ariflex, about Aleister Crowley, Sixto Rodriguez/Sugarman, Roger vs. Raffa, and so much more. And of course, for bringing me calm when I was scared and you understood why, and most importantly for allowing me to guide you when you needed someone. I love you David. You were the brother I never had, the mentor that I needed, the friend that was always there, and the light of my life.” —Anni Davis, family friend

An Appreciation of the World

Within a week of meeting David 20 years ago, he invited me as well as my teenage son Ruben and daughter Emma on a trip of a lifetime: a trek to Everest Base Camp with a crew of expert filmmakers and legendary climbers.

In March 2004, the kids and I joined director Stephen Daldry (Billy Elliot, The Hours) and producer Jon Finn as the five novices among a hardcore climbing team that included Jimmy Chin, Ed Viesturs, and Robert Schauer. Most were alums of the 1996 IMAX Everest movie (and rescuers of the survivors of that year’s tragedy). Curious about the three interlopers, the crew needed only to hear that David Breashears said we belonged, and we became a trusted part of the team.

My wife Rosemarie remembers, “David took seriously the responsibility of including our children. He had high expectations and told them it was ‘an adventure with serious climbers and filmmakers, but it was work,’ and to join the team, they had to physically prepare.” Though concerned for their safety, she added, “Trusting David was easy.”

David joined the team on the third evening, helicoptering to Namche after our group had bonded each night, cloistered around a stove pipe, playing crossword shootouts and sharing stories. My daughter Emma read Into Thin Air, and marveled at how the people in the book surrounded her. When he stepped into the hut that evening, a leader walked in. It was my first sight of David in his element.

He commanded respect because he demanded care. I witnessed how his uncompromising attention to detail could change the twinkle in his eye to a fiery flash if someone missed something critical to either safety or the beauty of their work. David’s demanding nature would produce impeccable filmmaking; and it would keep everyone safe.

Ruben, the 13-year-old on the trip, told me: “He insisted we take in and appreciate everything. He treated everyone on Everest—particularly the Sherpas—with love and respect knowing we were all just visitors there. It’s probably why he was the best person to film the mountain: he had an outsider’s eye, but he knew there was so much more complexity to the mountain than simply a physical milestone to conquer. It had generational and societal importance to the people who lived and worked there and symbolic importance to the world. Of all people in the world, he was the least capable of viewing the mountain superficially; he was too curious, passionate, and smart to fall into that trap.”

Now 33, Ruben recalls his friend David’s impact on his life. “I’ve never met anybody who put so much effort into gifting others with knowledge and an appreciation for the world.” —Steve Johnson, friend

Insatiable curiosity

My dear partner, Anni, met and worked with David more than 30 years ago. One of her greatest gifts to me, along with her dog Scout, was sharing her close friendship with David. Despite very different backgrounds, but with important similar interests, we also became very close. I had spent 12 years as an Air Force physicist and professor, followed by 20 years as an Army doc and flight surgeon. Though he didn’t have a formal college education, David was one of the brightest, most insightful people I have known, with an insatiable curiosity for essentially everything.

Among David’s favorite topics of discussion were aviation, rockets, space exploration and astronomy, our planet, politics, and the military. My youngest son becoming an F-15 pilot, and his deployments, added tremendous fuel for discussion. As a concerned father, despite my own military deployments, I will always appreciate David’s understanding and support.

Mountaineering had interested me my entire life and I had greatly enjoyed hiking up fourteeners in Colorado while stationed there. During a tough period after retiring from the military, my long talks with David and reading his book, High Exposure, were instrumental in making that transition.

I absolutely loved David’s quick, wry humor. He jumped on every opportunity to tease me about my driving and Minnesotan speak. For now, David, I just want to let you know I’m “pert-near” the summit and I’ll be there “right quick”! —Perry R. Malcolm, family friend

“My mom would be proud”

My most extensive time with David was as one of the ten climbers on the 1986 North Ridge Mount Everest Expedition, which he and Andy Harvard led. The two goals were to find the remains of George Mallory and/or Andrew Irvine and to have the first American woman summit. While neither happened, mostly thanks to the jet stream parking on the ridge, two documentary films were made. One, entitled “The Mystery of Mallory and Irvine,” was for the BBC. The other was for ABC’s “Spirit of Adventure,” and featured the American women and a small contingent of hang gliders who had hoped to soar from the summit.

David was a driving force, not just filming, but as an inspiration for all—including the Sherpas from Nepal, one of whom was a close friend of his. Dawanuru, who had been on one of the summit climbs with David, perished in an avalanche while descending from the North Col, where he and his team had recently ferried a load of oxygen and supplies. His passing created the final determination to end our expedition. David saw to the arrangements for Dawanuru’s immolation not far from our basecamp, and for the return of his ashes to his village. David and Andy set up a fund up to help take care of his family.

Over the ensuing years, I saw David frequently at American Alpine Club meetings and the Harvards’ house. In 2000, I awarded him—along with Caroline Alexander, writer and producer of the IMAX film “Endurance”—an honorary degree from Sterling College.

David’s comment was, “My mom would be proud. Now I have a college degree!” —Jed Williamson, former president, Sterling College

Source link