No products in the cart.

Outdoor Adventure

Luxury Gorpcore and the Aspiration to Be Outdoorsy

Earlier this fall, GQ’s Global Style Director, Noah Johnson, wrote an obituary for gorpcore: “[gorpcore] as a trend… is dead. Let it be known.” For the uninitiated, “gorpcore” uses an acronym for trail mix (“good old raisins and peanuts,” although that meaning is contested) to describe a style that involves wearing outdoorsy clothes as streetwear. The term, which has its origins in “normcore,” was coined by former New York Magazine writer Jason Chen in 2017.

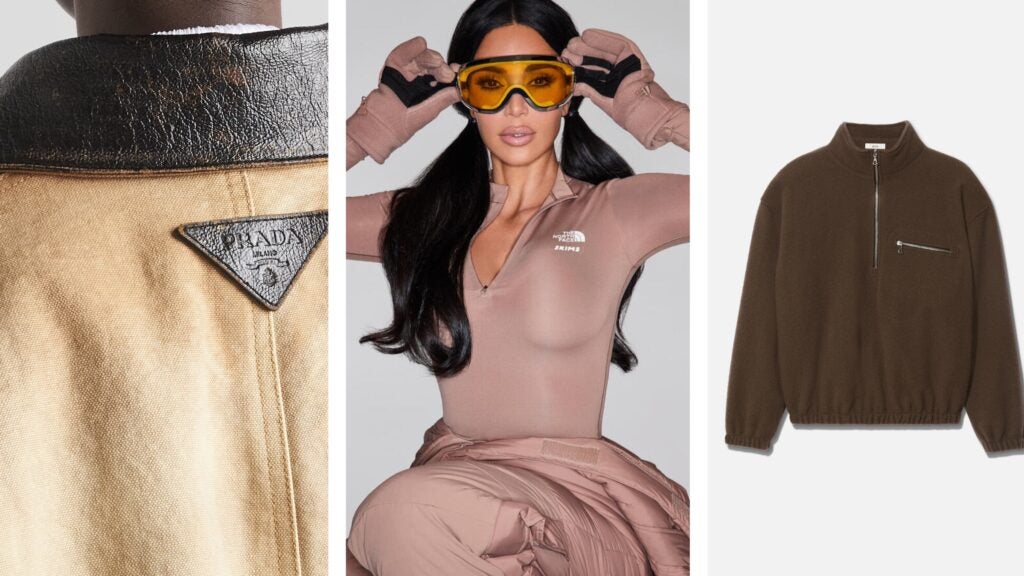

Here’s the thing, though, if gorpcore is dead, why is Prada selling $5,000 canvas “barn coats” (that look a lot like regular ol’ Carhartts)? Why are outlets like the New York Post still breathlessly publishing stories on $1,000 fleeces? Why did a collaboration between the North Face and Skims break the internet for a day? Why did the iconic ski brand Salomon set up a pop-up in Soho aimed at courting a new, high-fashion consumer base?

In reality, the title of the GQ piece, “RIP Gorpcore,” is a bit deceptive. When Johnson eulogizes gorpcore, he doesn’t mean that you won’t be seeing men and women from Brooklyn to the Harper’s Ferry headquarters of the Appalachian Trail in the North Face, Marmot, Salomon, and Patagonia. Instead, he argues that the style has become so ubiquitous it shouldn’t be considered a new trend anymore.

So where do $1,000 fleeces fit in?

To make sense of some of 2024’s most outlandish high-end outdoor wear, I talked to Derek Guy, the internet’s foremost men’s fashion historian, who helped me put the year’s key pieces into a broader context.

The Prada Barn Coat, a Cool $4,900

First up: Prada’s canvas barn coat, which the fashion blog In the Groove named “the biggest style trend” of 2024. The coat, which apparently became the hip-mom school dropoff garment in NYC last fall, looks like something Kevin Costner’s Yellowstone character might wear while taking a rideabout on the family ranch. That, plus the Prada triangle logo. Its price is listed at $4,900. (There’s also a cropped version, which sells for $3,700.) The Prada site describes it as “borrowed from menswear” and “enhanced with a distressed effect.”

“Distressed effect” really stayed with me. Isn’t there something a little ironic about a $4,900 pre-worn-out jacket that is trying to mimic the type of coat that someone would actually distress over time while wearing it, typically at work? I grew up in a small West Virginia town in the late nineties and early aughts. The men I knew wearing barn coats (Carhartts, specifically) definitely didn’t purchase them pre-distressed, and they certainly would have something to say about anyone who did.

But, according to Guy, something like the Prada canvas coat can really be seen as a celebration of the values associated with its original uses. From his point of view, all fashion choices are the result of the cultural values of the period from which they emerge.

Think about it: What other pop culture or trends might suggest that Western-adjacent, work-worn clothing would be having a moment right now that signals that culture is interested? Yellowstone is a great example. So are the insanely popular Ballerina Farm videos. Even cowboy boots have seen sales increases in recent years. And what are the cultural values associated with ranching? Hard work, fortitude, honesty, independence, self reliance, connection to the land, and traditional masculinity are a few that come to mind. These values are also tied deeply to at least one version of the general American ethos.

Guy says that when different groups become culturally respected and reflect societal values, their style choices—even if they’re initially made for technical functionality—end up influencing the broader population. Consider the fact that Marmot, Patagonia, and the North Face all have their own version of the canvas barn coat. (I love my Marmot prairie jacket that I bought a few years ago, and the only time I’ve been on the prairie is when I drove through it.) And it’s likely that none of those more traditional outdoor brands started with a vision of creating aesthetic rancher-style workwear coats. They likely also didn’t have a core customer base of ranchers and farmers looking to upgrade their jackets. The brands created these garments to meet emerging consumer taste.

Still, does close to $5,000 for a pre-distressed coat make any sense? “The reason we celebrate these things, but then also create absurdly expensive versions is because… individuals also seek status,” says Guy.

When there are enough versions of a beloved item to meet various individuals’ price points, one way to separate yourself from the rabble is to buy the really, really expensive one.

So ranching-farming-barn culture is having a moment. People are motivated to show status. I’m still good with my dad’s vintage Carhartt from the eighties, though.

$1,000 Fleeces

If people generally aspire to the life and values that go with the barn coat aesthetic—so much so that we’re now seeing super expensive luxury versions of the staple—how do thousand-dollar fleeces, like the ones Rier nearly sold out of this fall, fit in?

The answer is pretty simple. The values associated with outdoorsy lifestyles are also aspirational for many, even if they don’t have imminent plans for a long thru-hike in their orange Patagonia puffy. And what are those values? Hopefully they’re familiar to anyone who considers themselves an outdoors lover: adventurousness, self discovery, environmental stewardship, physical prowess, community, self sufficiency, and technical expertise to name a few. These values, plus the promises of escape and leisure that a trip to the wilderness can provide, roll up into gorpcore style choices. Add in the basic human desire to flex status, and it makes sense why you would end up with inaccessibly expensive all-wool fleece pullovers.

Hasn’t Outdoor Gear Always Been About Status?

My dad is a consummate outdoorsman. When I was young, he hiked and hunted. He taught me to identify North American trees and walk quietly through the woods. I have vivid memories of watching him and my uncles process a buck that they’d killed up a snowy run in West Virginia and then lugged back over the miles to a humble camp that served as their base. And they did all of it in Coleman gear.

It wasn’t until I went to college at an elite Southern university that Patagonia Synchillas entered my consciousness as a marker of status. The kids in the right sororities and fraternities all knew that you paired your Synchilla with Chubbies and artfully worn out Sperries. Those of us who didn’t come from quite the same backgrounds had to quickly make sense of the way core outdoor gear fit into the social hierarchy. I bought my first Patagonia fleece (not quite a Synchilla but close enough) at a steep discount as part of a bulk order my cross-country team made. I felt myself relax as I settled into its cozy heft on campus. Now, I think I own upwards of a dozen Patagonia, Marmot, North Face, and Cotopaxi fleeces and jackets. When I had the chance to signal my values and status, I seized it in the way Guy helped me understand.

Does that mean I’m going to start spending a grand on Austrian-made fleeces anytime soon? I’d like to say no, that’s a bridge too far, but consumer desire can be a funny thing. Even my own is a little bit unscrutable.