No products in the cart.

Outdoor Adventure

New Data Refutes the Need for Personalized Training Advice

A decade ago, a muscle physiologist named Brendan Gurd published a study comparing sprint interval workouts with longer continuous endurance workouts. Some people responded best to the intervals; others responded best to the continuous workouts. The implication was clear: to get the best training results, you need to figure out what type of workout you respond best to.

Those results fit in with a broader push in sports science to move beyond “average” responses and provide personalized training advice that would maximize each individual’s response. But last month, Gurd and his colleagues at Queen’s University in Canada published another paper, the culmination of a long journey in which they concluded that they were wrong—that the individual variation they observed in that 2016 study was a mirage.

Their new conclusions, which mirror the results of numerous studies from multiple research groups around the world studying both strength and endurance exercise, are hard for scientists and athletes (and, to be honest, journalists) to accept. After all, isn’t it obvious that some people get a bigger bang for their training buck than others? Even Gurd struggles with the idea: he’s a cyclist, and he sees riders in his regular group rides who seem to respond more than others to the same training advice. But the data says otherwise.

Responders and Non-Responders

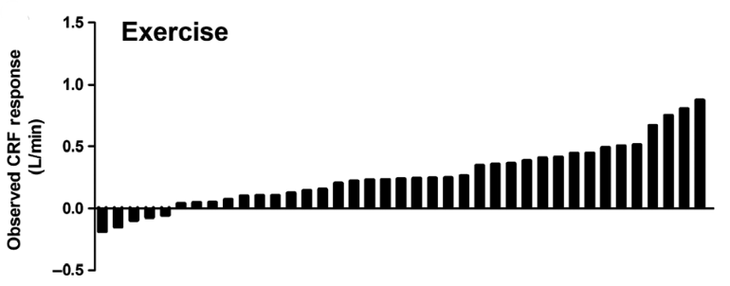

One of the big trends in sports science when Gurd’s initial study came out was to report individual results rather than just an overall average. Say you put a bunch of people through a 24-week training program, tailored to their individual baseline fitness so that they’re all working equally hard, and observe that their VO2max jumps by about 10 percent (or, in the units shown in the graph below, about 0.2 liters per minute), on average. That’s great, but not everyone increases by exactly 10 percent. Instead, you’ll see a range of individual responses like this (each bar corresponds to the change in VO2max of an individual subject):

On the right, you’ve got some very strong responders. In the middle, you’ve got average responders. On the left, you have some people who actually got less fit after 24 weeks of training. Shocking!

This idea of non-response to exercise got a lot of attention in the early 2010s and led to the boom in personalized training advice, but it also prompted a backlash from statisticians. How do you know those variations are caused by exercise, rather than by measurement errors or other lifestyle factors like diet, sleep, or stress? There’s no way to tell from a graph like the one above. Instead, you need to compare those results to a control group that did nothing for the same period of time.

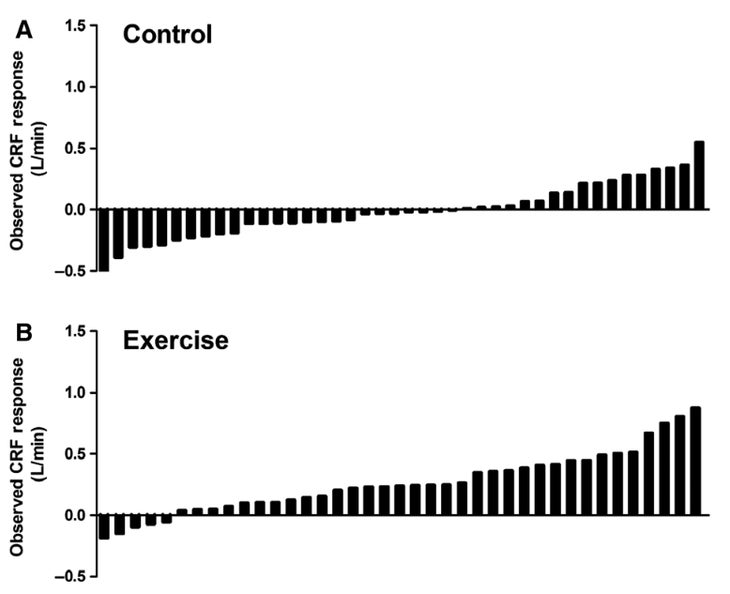

The vast majority of studies purporting to find responders and non-responders don’t have a suitable control group. The data above is from one of the rare studies that did have a control group that did nothing for 24 weeks, reanalyzed by Gurd and his colleagues in Physiological Reports in 2019. Here’s what that data looks like:

We see exactly the same variation in response in the control and exercise groups. The only difference is that the exercise group is shifted upward by the average response of about 0.2 liters per minute. So the variation in response can’t be because some people “respond” to exercise (or to the specific workouts prescribed) while others don’t—because the subjects in the control group had a similar range of response and non-response to doing absolutely nothing.

The New Data on Personalized Training Advice

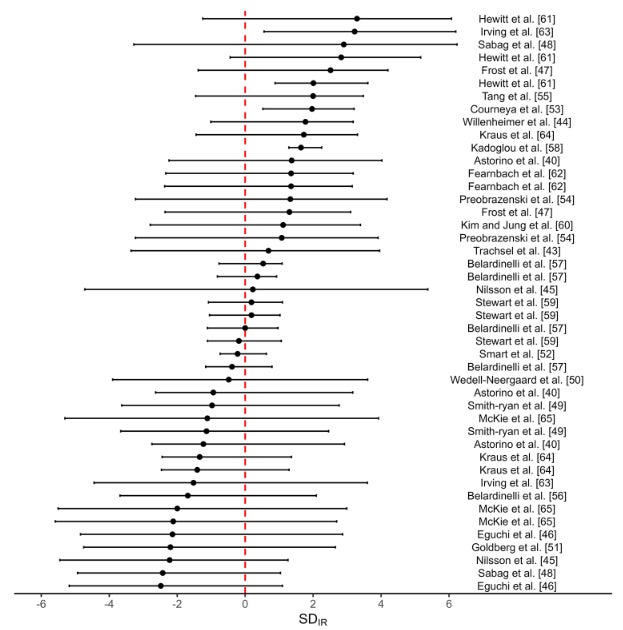

Gurd’s new study, which was led by grad student John Renwick and is published in Sports Medicine, runs a more rigorous version of this analysis on a massive data set drawn from 24 studies with 2,230 participants. This is every study they could identify in which subjects did a standardized and supervised exercise program, measured VO2max, and included a control group that did nothing.

The main analysis compares the standard deviations—a measure of how much individual variation in response there is—for the changes in VO2max in the exercise group and the control group. If there’s true individual variation in response to exercise, then the standard deviation should be bigger in the exercise group than the control group. If the standard deviations are the same, it suggests that the response is uniform across individuals.

Here are the results for 45 different tests (some of the studies included more than one training group):

The values to the right of the dashed line indicate that the standard deviation was bigger in the exercise group. So the studies shown at the top of the graph do seem to indicate individual variation in response. But the studies at the bottom show the opposite effect, seemingly (and nonsensically) indicating that there’s more variation in response to doing nothing than to exercise. There’s a roughly equal number on each side of the line, and the error bars of nearly all the studies include the dashed line. Crunch the statistics, and the overall conclusion is that there’s no evidence of variation in individual response.

This result doesn’t come out of nowhere. After that initial 2016 study, Gurd realized that before searching for why some people respond better to intervals and others to continuous training, he needed to demonstrate more rigorously that it was true. In one follow-up study, he essentially repeated the 2016 protocol except that the volunteers completed two identical four-week training routines, separated by a three-month washout period. Once again, he found that some people responded best to the first training protocol and others to the second protocol—a clear sign that the variation wasn’t a result of the specific exercises prescribed.

And it’s not just endurance exercise and VO2max: numerous strength training studies and meta-analyses, like this one by Solent University researcher James Steele and his colleagues, have reached essentially the same conclusion using similar statistical methods. That runs counter to what we usually assume about how some people put on muscle more easily than others, and it even clashes with the findings of a study I wrote about earlier this year suggesting that some people benefit from doing more sets of weight-training while others benefit from sticking to fewer sets. More studies are planned to search for the elusive signal of individual response variation, Steele told me, “though at this stage I think it’s flogging a dead horse to try looking for it.”

What It All Means

There are some very good reasons to think that variable response to exercise does exist. Back in the 1990s, a major research initiative called the Heritage Family Study tried to figure out whether individual genetics might influence how people respond to exercise. Sure enough, they found that the VO2max response to training seems to cluster within families; overall, they estimated that around half the response to exercise is genetically determined.

There’s also animal data, with successive generations of rats bred to have low or high response to training. And then there’s the lived experience of athletes. “I still do believe there’s variability in response,” Gurd told me. “But we can’t demonstrate it.”

If there is true variability in training response, though, it seems to be trivial compared to other sources of variability. One of the main ones is measurement error: if you’re measured slightly below your true value on the baseline test and slightly above on the final test, you’ll look like a strong responder—and vice versa. There’s also “within-subject variability”: changes in behavior or environment that have nothing to do with the exercise program being tested, like sleep, diet, or stress. These external factors might even be influenced by your genes, which could explain the Heritage results.

All this might seem like bad news if you were dreaming of a bold new era of individualized workouts based on your unique training responses. But it’s great news if you want simple, actionable exercise advice. The workout plans and training principles that work best for the average person in large studies, or that have been honed through decades of real-world experimentation by athletes and coaches, are almost certainly the same plans and principles that will work best for you. We’re all individuals, but training is training.

For more Sweat Science, join me on Threads and Facebook, sign up for the email newsletter, and check out my book Endure: Mind, Body, and the Curiously Elastic Limits of Human Performance.

Source link