No products in the cart.

Outdoor Adventure

New Research Reveals the Physiological Effects of Backyard Ultras

How fast is the backyard ultra craze growing, you ask? Last month, Dan England wrote a great feature for RUN detailing the rise of the quirky race format, which was introduced by Barkley Marathons founder Gary Cantrell in 2012 and involves completing one 4.167-mile loop every hour on the hour (adding up to 100 miles per 24 hours) until you give up. At the time, the world record was Harvey Lewis’s 108-lap performance, which works out to 450 miles in four and half days.

Now, just a few weeks later, Lewis is down to fourth in the rankings after three Belgians notched 110 laps to win the Backyard Ultra World Team Championships, which featured teams from 61 countries. Cantrell estimates that at least 25,000 people have run official backyard ultras this year alone. What started out as a novelty race is now a surprisingly popular way of testing your limits—which makes the format intriguing to scientists seeking to understand what defines those limits.

Sure enough, the first study of backyard ultra racers was recently published in the European Journal of Applied Physiology. It’s from a team of Belgian researchers, appropriately enough, led by Kevin De Pauw of the Vrije Universiteit Brussel. They ran a series of physical and cognitive tests on 12 competitors (including at least one of the new world record holders, as far as I can tell, though the data is anonymized) before, during, and after a backyard ultra event that took place in April 2023. Here’s what they found.

Backyard Ultras Are Not Just About Physical Limits

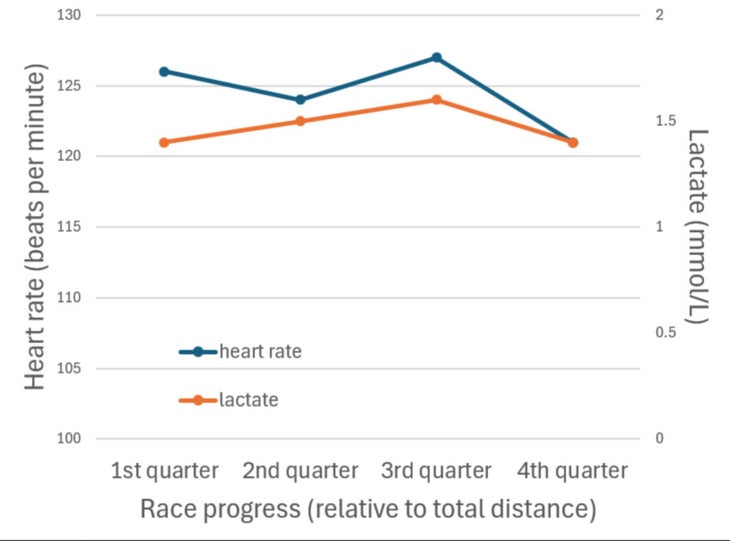

It’s a truism to say that races become progressively more about the mental side than the physical side as the distance gets longer. How high did the competitors push their heart rates before reaching exhaustion? How much lactate was coursing through their veins? Not that high and not that much, actually. Both heart rate (which was measured continuously throughout the race) and lactate levels (which were assessed with a blood test every four hours) stayed fairly constant throughout the race, if anything dipping slightly towards the end.

The competitors completed an average of 34 laps, with a range from 14 to 63. To compare across this range, the research broke the data down into quarters for each racer. Here’s what that data looked like:

The peculiar format of the race makes the data a bit tricky to interpret. The overall pace is set in stone: you have to cover 4.167 miles every hour, but you can’t cover more than that. If you run faster, you just get some extra rest—and time to fuel up and hit the bathroom—before the next lap. On average, the racers got 12.4 minutes of rest at the end of each lap, with a range from 1.1 minutes (cutting it close!) to 25.8 minutes.

With this pacing constraint, it’s perhaps not surprising that heart rate and lactate stayed steady even later in the race. The required pace is a little slower than 14 minutes per mile, so the question isn’t whether your legs can move that fast; it’s whether you can summon the will to ask them to keep moving for another lap. “The most challenging part,” Cantrell told England, “should be the distance between the chair and the starting corral.”

It’s Not Just About Brain Fatigue, Either

There’s a lot going on with the mental side of backyard ultras. Sleep deprivation is the most obvious factor, with nothing but occasional micronaps available for several days. It would be extremely challenging to play tiddlywinks for that long, let alone to keep running 4.167 miles every hour.

Surprisingly, though, the tests of cognitive function administered by the researchers weren’t as horrifying as you might expect. The competitors performed simple reaction time tests every four hours throughout the race. There was no significant worsening during the race: the slowing effects of fatigue and sleep deprivation were balanced out by the positive effects of exercise on brain function, the researchers posit. Once the event was over, reaction times did get worse—but the slowdown wasn’t proportional to how long the competitors lasted in the race. There were some minor changes in other cognitive tests performed before and after the race, but nothing that explains why people give up or what separates the best from the rest in this event.

Fatigue Resistance Makes Champions

Over the last few years, there’s been a surge of interest among researchers into a trait that is sometimes dubbed “the fourth dimension of endurance” and has various more formal names: durability, physiological resilience, fatigue resistance. The idea is that measuring traits like VO2 max and lactate threshold and running economy (the three classic dimensions of endurance) in the lab tell you how good someone is when they’re fresh—but that what determines who wins long races is how much those values degrade when you get tired.

In a 2022 study, University College Dublin researcher Barry Smyth and his colleagues looked at Strava data from 82,000 marathoners and assessed the ratio of heart rate to running speed as their race progressed. The idea is that this ratio gives you a measure of fatigue resistance: if your speed at a given heart rate drops (or, equivalently, if your heart rate at a given speed increases), that suggests that your physiology has deteriorated from its starting values. Perhaps you’re running less efficiently, or you’re no longer able to deliver as much oxygen to your muscles. Sure enough, Smyth found that faster marathoners tended to have better fatigue resistance—that is, their heart rate-to-speed ratio stayed closer to its starting values for longer.

De Pauw and his colleagues ran a similar analysis for the backyard competitors, and found a similar pattern. Runners who completed more than 35 laps had a relatively constant heart rate-to-speed ratio throughout the race. Even after a couple days of running, the required pace still elicited basically the same heart rate. Those who completed fewer than 35 laps, on the other hand, saw their heart rate climb in the second half of their race, with a particularly steep climb in the final quarter.

For Backyard Ultras, It’s the Effort That Counts

This fatigue resistance pattern is interesting, and scientists have come up with various hypotheses about how to improve fatigue resistance: higher training volume, better fueling, more even pacing. But it’s clearly not the sole explanation for why runners eventually give up in a backyard ultra.

Instead, the clearest smoking gun in De Pauw’s data is actually much simpler: subjective rating of effort, which was assessed on a scale of 6 to 20 every four laps. Effort is a somewhat nebulous concept: a definition I like is that it’s “the struggle to continue against a mounting desire to stop.” It’s your brain’s way of integrating all the different incoming signals from your body, mind, and environment: how hard you’re breathing, how fast your heart is beating, how hot you are… but also how tired or bored you are, whether there are spectators cheering you on, and so on.

In the first quarter of the backyard race, effort ratings averaged 9.7; then 11.7 in the second quarter, then 12.5 and 16.0 (which corresponds to something between “hard” and “very hard”). There’s compelling evidence that in shorter exercise bouts, it’s effort rather than pain that maxes out and forces you to give up. The new data from backyard ultras suggests the same is probably true even in races lasting several days. The specific signals that make the effort feel progressively harder differ from event to event—but ultimately, whether you’re racing a mile or a multi-day backyard ultra, your sense that it’s simply too hard to continue becomes a self-fulfilling prophecy.

For more Sweat Science, join me on Threads and Facebook, sign up for the email newsletter, and check out my book Endure: Mind, Body, and the Curiously Elastic Limits of Human Performance.

Source link