No products in the cart.

Outdoor Adventure

Nostalgia: A Hobby, a Habit, a Survival Tactic

At some point during the second or third episode of Once Upon a Time in Queens, I started thinking maybe I was using nostalgia as a sort of nondrug antidepressant. Keith Hernandez was on my TV, reminiscing about the 1986 Mets, and I was right there with him, reliving the team’s 108-win season, playoff run, and World Series victory over the Red Sox as if it were all just yesterday.

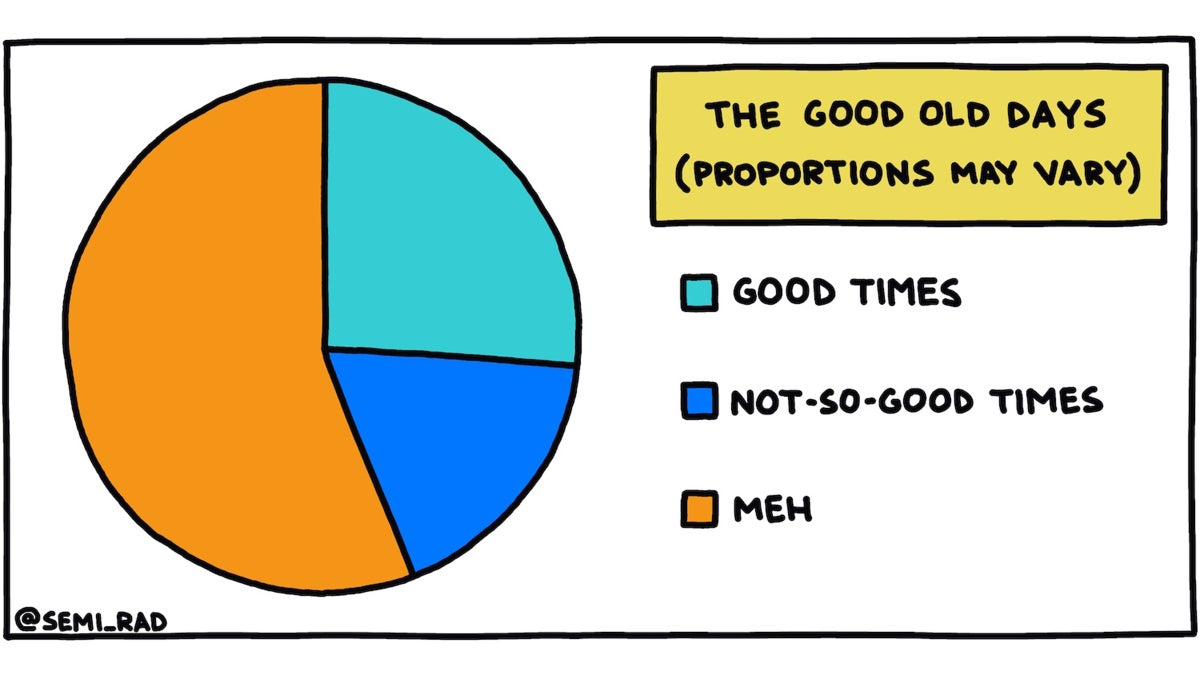

Except I have no memory of watching a single Mets game that season, or even being aware that they won the World Series. I was seven years old, have never been a Mets fan, and didn’t even start collecting baseball cards until the next year. So the Mets documentary was fun, but it wasn’t my nostalgia—it was vicarious nostalgia, for someone else’s “good old days.”

During the pandemic, I began watching more sports documentaries, starting with The Last Dance, a couple months into the first period of isolation. And then others, sometimes about teams I hadn’t even followed at the time or events that had taken place before I was born. Why did I, a person who watched zero hours of Boston Celtics–versus–Los Angeles Lakers games before 1990, now need five hours of content about the 1980s Celtics-Lakers rivalry?

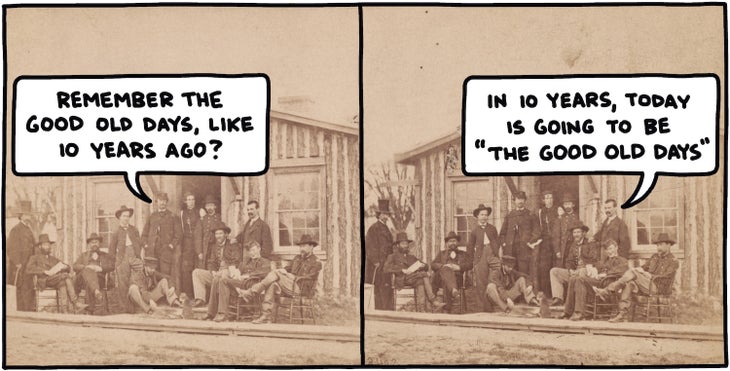

In the adventure world, there has long been a saying that there are three types of fun (maybe explained best in this piece by Kelly Cordes). Basically:

Cordes sagely points out that type-three fun can, once enough time passes, shift to type-two fun.

For about seven years, rock climbing was my absolute favorite thing to do in the entire world. Every weekend I would find a new place to go climb, and every week I would think about it, read about it in books, and scour websites and guidebooks for beta. Then I started to realize, for a few reasons, that I wasn’t having that much fun doing it anymore, and I became less obsessed and then basically switched to trail and ultra running.

I have so many memories of the times I spent on a small ledge on the side of a cliff, tied into an an anchor, belaying my partner coming up beneath me or leading the next pitch above me; or standing at the bottom of a rock wall jutting out of the trees, racking up at the base of a pitch I wasn’t sure I could lead; or sitting at the top of a multi-pitch climb, watching birds catch thermals, looking at the mountains, glad I was done with the scary part of the day and just had to figure out how to get back to the car.

Sometimes I think I miss climbing and all those things that make it so singular: a perfect hand jam in a splitter granite crack, the feeling of unlocking a set of moves that from below looked impossible, the smell of climbing rope as I flaked it out at the start of what would hopefully be another great day.

Most of the time, though, I think I just miss being young. Or not really young, but younger, in a place in life where I made space to do something that, in the grand scheme of things, was so unimportant but was important to me.

Page two, Alright, Alright, Alright: The Oral History of Richard Linklater’s Dazed and Confused, by Melissa Maerz:

“Obviously, I draw a lot of creative inspiration from the past, what people would call nostalgia,” says Linklater, who is surrounded by classic movie posters in his office in Northeast Austin. “But when I was making Dazed, I was thinking about how nostalgia can be a dangerous thing. People are nostalgic for times that never fucking existed. When you think about the past, you have to try to remember what was really going on. When people say, ‘Oh, those were the good times!’ I always have to remind them, ‘No, that time sucked.’”

This was the surprising goal behind Dazed and Confused: he wanted to show how much the ’70s sucked.

As a thoughtful teenager growing up in the East Texas town of Huntsville in the late 1970s, Linklater was disgusted by adults’ nostalgia for the 1960s. “What a great time,” he says, laughing. “Rioting, war, assassinations!” But his generation ended up having the same feeling about the 1970s. That’s just the way nostalgia works: It is not a collection of memories, but a reinvention of memory itself. It’s misremembering your own life on purpose.

“Go Ahead, Binge Old Movies and Jam Out to ’90s Hits: Decades-old movies, songs and video games have surged in popularity over the pandemic. Psychologists say conjuring nostalgia during stressful times is a healthy coping mechanism,” The New York Times, November 10, 2020:

Research shows that conjuring nostalgia by watching old movies or taking up old hobbies is an effective way to cope with stress and anxiety. It can lift people into better moods, boost confidence and inspire a sense of optimism, said Dr. Wing Yee Cheung, an associate professor in psychology at the University of Winchester in England who studies nostalgia.

“We feel that we have lost footing at the present time, and we gain some comfort by taking a step back and revisiting something that reminds us of a time that we used to feel more connected with other people,” Dr. Cheung said. “It gives you energy to cope with what is going on now and move forward.”

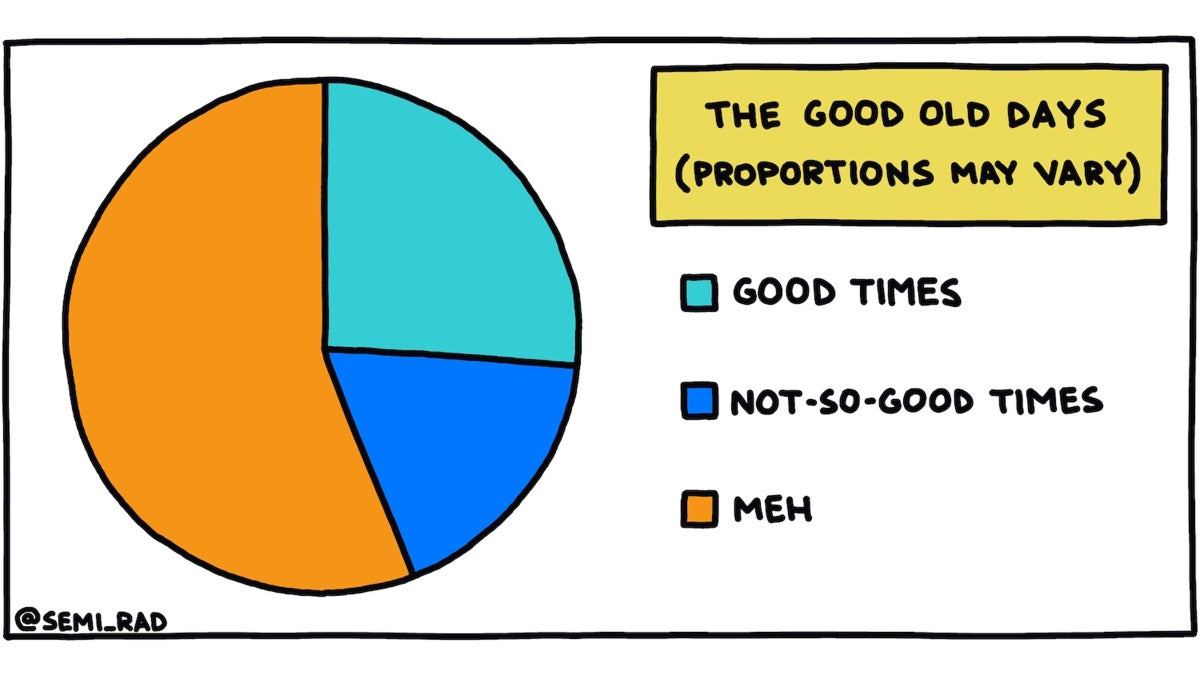

I’m aware of the dangers of nostalgia: believing, for example, that a place was great 10 or 15 years ago, when I first discovered it—but now it’s too crowded or such-and-such group of people is ruining it. Whether you’re talking about a rock-climbing destination or a country whose population demographics have changed over the years, your “good old days” probably weren’t universally great for everyone. And talking shit about music that’s not as good as the music was 10 or 20 years ago doesn’t make you an astute critic; it just makes you old.

There’s a saying I think about a lot, that I swear was mentioned in an old Mountain Gazette story about bumper stickers, and it went something like “This place started going to shit 15 minutes after I got here.” Which is an attitude I generally try to avoid having. As my friend Ace once said to me, “There’s nothing worse than a jaded local.”

Despite my best efforts to be present or in the moment or just a person who recognizes they are having fun while they are having fun, I generally suck at what I would call being happy. I do this thing every night with my wife, Hilary, where we ask each other, “What made you happy today?” and we each list off three to ten things, most of them not exactly earth-shattering: My first cup of coffee this morning. Making progress on my book project. Giving Rowlf a belly rub. Gnocchi. Talking to a friend on the phone. The sunset.

I try, but I have found that I am way better at recognizing a good time in retrospect than while it is actually happening. My iPhone randomly (I think?) shows me a photo from five years ago, or a year ago, or even six months ago, and I look at the photo for a second, recognize where the photo was taken, and am reminded of a good trip, or a good day, or a good time, even if it’s just an image of the late-afternoon sun poking through a stand of lodgepole pines, a photo I might have just taken to put on my Strava record of my trail run. I literally think to myself, That was a good day, even though I 100 percent did not say “This is a good day” when it was happening.

So my entire life is a sort of type-two fun, not fun while it’s happening but fun in retrospect? Maybe I’m taking this whole thing too seriously.

I talked to my friend Forest last week, and he was having a much better winter this year than last year, when he’d broken his leg and spent months laid up and then rehabbing it, which was challenging and depressing. But around town the other day, he’d seen a woman with a broken leg, and he’d had a weird tinge of nostalgia for last year, when he’d been miserable with his broken leg.

Sometimes I hear a song that reminds me of some of the really sad times in my life: Tycho’s “Coastal Brake,” when my girlfriend and I broke up and I spent the latter half of the year driving around the West living out of a station wagon; Gregory Alan Isakov’s “The Stable Song” the summer my grandmother died; or that whole first Bon Iver album for the summer I was getting divorced.

I still love those songs, probably way more than songs that remind me of happy times. Some days, when I need to sit down and focus on writing, I queue up some sad shit on Spotify. I don’t know why.

When Hilary and I first got together, I talked her into moving into my van with me. It was not a nice van—it was a 2005 Chevy Astrovan, lacking many YouTuber-friendly features, such as any sort of indoor cooking apparatus, enough room inside to stand up to get dressed, or anything to sit on besides the bed or two bucket seats.

Within the first month, which was also month number seven of our relationship, I got either food poisoning or some sort of intestinal bug while we were in northern Arizona, and luckily we had enough money to get a $39 room at the Quality Inn for a couple nights while my body expelled … well, to quote Dani Rojas, the Latin footballer character from Ted Lasso, “To be able to do both those things at the same time? The body is a miracle.”

This was (checks calendar) nine years ago. I brought it up the other day, and neither of us said it was fun but we started reminiscing about that time in our lives and a few of the other minor discomforts of it. But fondly. We were having nostalgia for the not so fun parts, which is a thing I do, I guess. Because what is a fondness for moments in the past, good and bad, if it’s not a way of reminding myself that I love my life?

Brendan Leonard’s new book, I Hate Running and You Can Too, is available now.

The post Nostalgia: A Hobby, a Habit, a Survival Tactic appeared first on Outside Online.

Source link