No products in the cart.

Outdoor Adventure

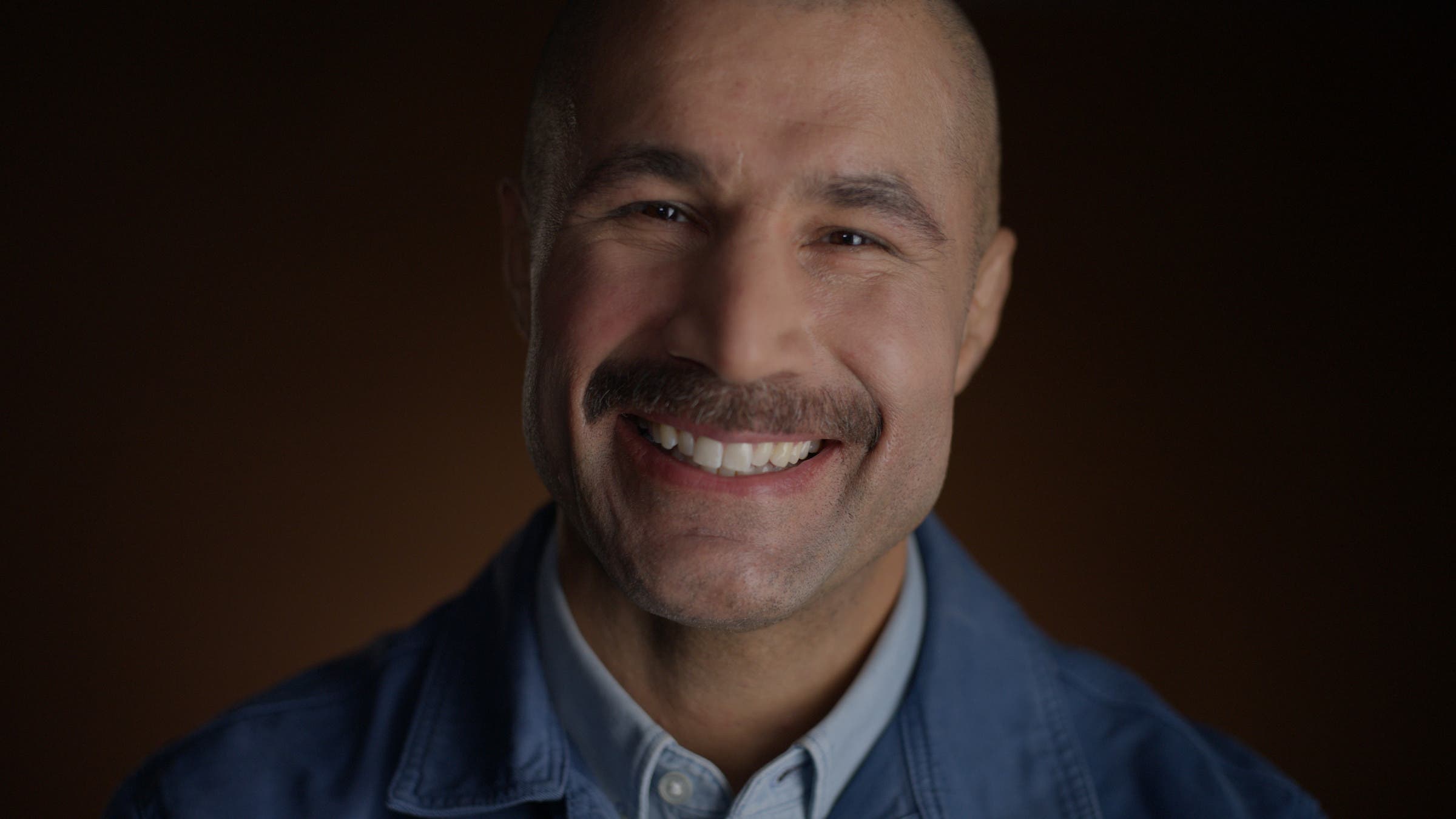

Richard Parks on Exploring Antarctica and ‘Pole to Pole’

Published January 3, 2026 03:42AM

Richard Parks was once a professional rugby player, but after a career-altering injury, he began to pursue polar exploration. To date, he has skied more solo, unsupported, and unassisted miles in Antarctica than anyone else. He also holds the record for undertaking the most solo expeditions in Antarctica. Parks is the first person of color to ski solo to the South Pole, and the first Welshman to do so, as well.

In a recent expedition, Parks helped Hollywood star Will Smith reach the South Pole for the upcoming National Geographic docuseries Pole to Pole. In Pole to Pole, which premieres January 13 on National Geographic and January 14 on Hulu and Disney+, Smith travels to the seven continents to explore what he calls “the edges of our planet.” In episode one, Parks works with Smith to ski and ice climb in Antarctica.

Outside talked to Parks about the show, his career, and what it takes to survive for days alone in unforgiving climates.

OUTSIDE: Can you tell us about your background?

Parks: For most of my life, I’d been a professional rugby player. That career was cut short by injury. It was a really difficult period of my life emotionally. My grandmother passed away two years before my injury, and her funeral was a bit of a blur. It was in the morning, and I was back in training in the afternoon. But I was very close to her, and it was like the vicar shouted this particular sentence in his eulogy: “The horizon is only the limit of our sight.” I had it tattooed on my arm.

Fast forward two years, after a period of poor mental health following my injury, the realization of the vicar’s sentence really hit. I’d always told myself the story of rugby being the end. Of course, there’s life after sport. But I needed that inspiration to give myself the courage to pick myself back up and start moving.

And then I picked up a book about a British explorer named Ranulph Fiennes, and I was hooked. First, it was the courage to literally take the dog for a walk, to get connected with nature. I had never climbed a technical mountain at that point in my life. I’d always grown up outdoors. I used to race motorbikes, and we went camping as a family in the summer holidays. But I had never climbed the technical mountain.

How did you begin your career in expeditions?

My first project was the 737 challenge, a race to reach the highest points on all the continents—and the North and South Poles and Mount Everest—in seven months. Of the two years that we spent developing that project, along the way, I met people who became mentors, teammates, and sponsors. Of those two years, I spent 18 months in a tent somewhere on expedition, amassing a lifetime of engineering skills. I didn’t want to shortcut it with infrastructure from a commercial team. I used all of my life savings, including the insurance policy from my injury, to fund that. And in 2011, I became the first person to climb the Seven Summits and stand on the North and the South Poles in a single calendar year. That really was the gateway to the last 15 years of my life.

How did you handle that transition from rugby to exploration?

I worked really hard to change my body shape and lost over 20 kilos (44 pounds) in muscle mass. I transitioned from a power-based athlete into an endurance athlete, but to be really blunt, that kind of stuff is less important than amassing the technical skills required to perform safely. That’s been done through the friendships that I’ve made, the companies I work with, and time in the field.

But as a professional athlete, I was terribly nervous before games. At that point in my life, I would never share that or tell anyone. Now, I think that there’s a lot more confidence within athletes, particularly male teams, to have those conversations. But at the time, I was alone. I think that perspective gave me a sense of humility that’s required to perform in wilderness environments, particularly polar regions, because for all the meticulous planning and preparation and technical and physical performance, you will always be insignificant to Mother Nature. I’ve seen so many people in these environments who take an expectation of control into wilderness environments, and I’ve seen people unravel really quickly. It’s ironic that that’s been a big part of my ability to perform really well in these environments. It’s never been about outwilling or conquering these environments. For me, it’s about submission and symbiosis. That’s probably been the most profound transition.

How do you take care of your mental health when you spend so many days in isolation in such an extreme environment?

I’m a team player. Everything I’ve ever done has been rooted in a shared experience or a collective goal. All of the expeditions I’ve done have had some element of education or shared learning, whether that’s through my partnership with universities and schools or the Welsh government. So what keeps me sane in isolation is purpose, and being part of something bigger than the expedition.

Also, I always allow myself one luxury on every expedition. It all has to do with weight and size. But the first time that I created this rule was the first leg of my 737 Challenge, and it was the Antarctic leg. I packed a Christmas card from my mom and dad. I spent Christmas Day on the ice, and at that point, the adrenaline had settled for my project. I was missing home, and I was really excited to open this card. I opened it expecting a heartfelt poem or a message of inspiration. And I opened it, and I literally said, “To Rich. Love, Mom and Dad.” To this day, it is the shittiest luxury I have ever taken.

Now, normally, one of my frequent luxuries is Jelly Bellies. They create this ritual at the end of the day: I get my tent, and I have a certain amount of Jelly Bellies per day. I eat them one at a time and try and guess the flavor. Or I take a Walkman. Never both.

What do you eat out there besides Jelly Bellies?

Over the course of different expeditions, I’ve had a variety of different rationing strategies. On my last solo expedition, which was completed in 2020, I was carrying 1.1 kilograms (2.43 pounds) of food rations every day, which had a calorific payload of about 7,000 calories a day. I knew that I would burn 9,000 to 12,000 calories every day during that particular expedition. My strategy was long, long days to compensate for the softening conditions in Antarctica. So unable to move quickly, it was about skiing for longer days. On that expedition, I took in 600 calories every hour and 15 minutes. So I didn’t, I didn’t really have you kind of standardized three meals.

My strategy is always to ski for one hour and 15 minutes and then have a five-minute break. I’m incredibly regimented in that environment. For me, performance in that environment is about discipline and routine. So after one hour and 15 minutes, I would have some kind of hot drink and some kind of food. It might be Flapjack, or it might be something else.

I work with students at Cardiff Metropolitan University as part of an applied learning project where students designed all my equipment for the expedition. So over the course of two years, students from the School of Food, Produce, and Dietetics designed, cooked, and manufactured all of my food rations. Without a doubt, it was the most successful food strategy I’ve had. I lost around nine kilograms (19.8 pounds) of body weight. The most I’ve lost is 16 kilograms (35.27 pounds) over 42 days.

How has this second career changed your perspective on life?

I feel more at peace with myself. The connection with nature has been profound to me through adulthood and parenthood. It’s become part of my purpose to enable others to create emotional connections with the parts of the planet that I’m privileged enough to go to. Every project I’ve created and undertaken has had some kind of shared learning or scientific objective to it.

I interact with so many people who, whether they articulate it or not, have this profound disconnect with our planet, and I can understand that because, for a period of my life, I felt like that. However, that really saddens me now. So the opportunity to be a part of a series like Pole to Pole is an incredible privilege. When somebody like Will Smith is courageous enough to be vulnerable and to immerse himself in, for my episode, Antarctica, the audience is able to see themselves through Will. That’s incredible, and that’s something I’m really proud to be a part of.

This interview has been edited for clarity and length.

Source link