No products in the cart.

Outdoor Adventure

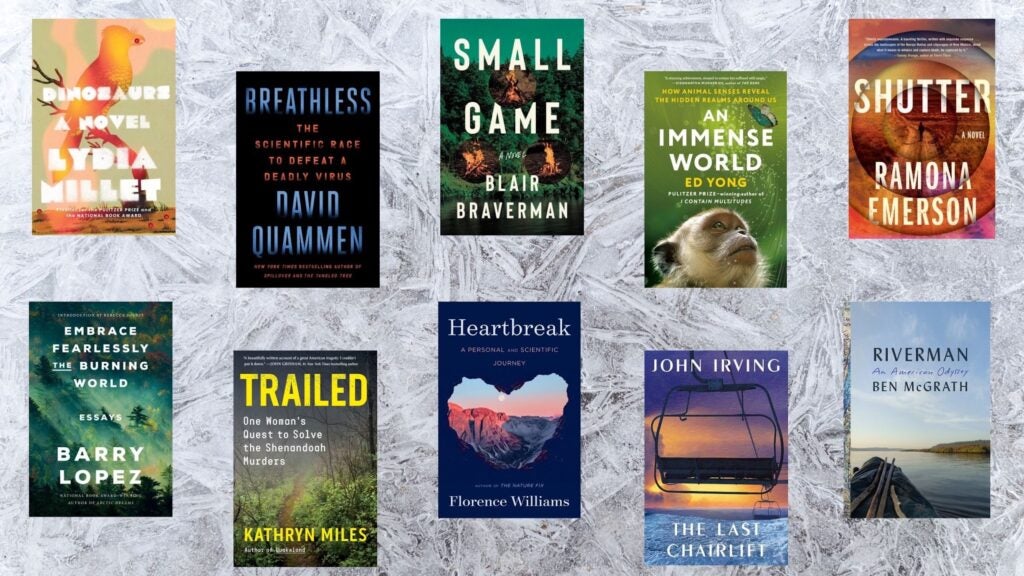

The 10 Best Books of 2022

Survival can be beautiful. At least that’s the message from our chilling, funny, and ultimately big-hearted favorite reads this year. From a reality show that goes delightfully wrong to a divorced woman taking to the wild alone, our picks blend science, memoir, and fiction to create a patchwork of the big, scary, bumpy world. It’s not that things don’t go wrong—there is murder in these pages. But after several years of COVID, we can finally sit back with a book that examines the pandemic in the rear-view mirror. And we can remember to look outward and marvel at the changing world around us, even as it burns.

Small Game: A Novel, by Blair Braverman

The not-so-secret little secret about survival reality TV is that there’s a camera crew there the whole time, munching on granola bars and drinking cool water. But what happens when that setup goes wrong? That’s the premise behind Outside contributing editor Blair Braverman’s debut novel, Small Game, in which the participants of the show Civilization brave the dense Wisconsin woods in faux-prehistoric tunics and sandals. Braverman, a dogsledder and author of the 2016 memoir Welcome to the Goddamn Ice Cube, is no survival slouch herself; she appeared on Discovery’s Naked and Afraid in 2019. The deal with Civilization, she writes here, “was that they’d found one another in the wilderness, this group of strangers, and over the course of six weeks would be tasked with building a new kind of community, something pure and sustainable and right. They would forgo all comforts, so that viewers didn’t have to. They would be one with the forest. They would find a way to live.” Or maybe they wouldn’t.

Breathless: The Scientific Race to Defeat a Deadly Virus, by David Quammen

Breathless is a different kind of reality thriller, scarier and far more chilling. A finalist for the National Book Award, it recounts, as the title suggests, virologists’ desperate attempts to decode the novel coronavirus SARS-CoV-2. After decades on the natural science beat, including as Outside’s Natural Acts columnist, Quammen has slogged through jungles and bat caves with virus detectives, and is singularly equipped to chronicle the tik tok of their work during the pandemic. Confined to Zoom interviews, he wasn’t able to get out into the wilds he’s explored in his previous work. But what he brought back has a terrifying beauty nonetheless. Viruses are like fire, he writes, “the dark angels of evolution, terrific and terrible,” without which “the immense biological diversity gracing our planet would collapse like a beautiful wooden house with every nail abruptly removed.”

Heartbreak: A Personal and Scientific Journey, by Florence Williams

What does it mean to have a broken heart? Florence Williams never set out to answer that question until her husband told her their marriage was over. Reeling both emotionally and physically, she set out to understand her trauma through the lens of her work as a science journalist. The result illuminates what our minds and bodies really go through when we split, and what it means to set out alone. In Williams’s case, that journey included setting out in a canoe down Utah’s Green River. “What did I really want to do?” she writes. “I wanted, of course, to be fixed—to transform into a woman ready to take on the rest of her life, to launch my boat as a means of launching myself into a better future. I wanted to individuate away from my moribund, fossilized identity as part of a couple. To do that, I wanted to access my bravery, something women of my generation aren’t often taught.” Don’t miss out on the audio version, an immersive experience named as one of Apple’s best audiobooks of 2022. Just don’t read it when you’re still mid-breakup: the early moments of Williams’s divorce will rip your heart out.

Riverman: An American Odyssey, by Ben McGrath

A journey down the Green River would be just another jaunt for Dick Conant, the itinerant paddler at the heart of Ben McGrath’s excellent Riverman. As we wrote here in April, Conant “first took to the nation’s rivers in 1999 at age 49; living in Boise, Idaho, fed up with everything, he bought a plastic canoe at Walmart, plopped it into the Yellowstone River, and headed for the Gulf of Mexico.” But just months after McGrath met Conant by chance on the Hudson River, the paddler went missing in the swamps of North Carolina, leaving an overstuffed red canoe and a slip of paper bearing McGrath’s number. An overall-clad fellow with a big white beard, Conant became a sort of folk hero in a riverine America of drifters and good Samaritans far from our divisive country today. “The generosity and kindness,” McGrath writes, “the sense of community, amid a nation that seemed otherwise to be pulling apart at the seams—were a large part of what had so struck me when visiting with Conant beneath the Hudson Palisades.”

Trailed: One Woman’s Quest to Solve the Shenandoah Murders, by Kathryn Miles

In May 1996, two hikers disappeared in Virginia’s Shenandoah National Park; rangers ultimately discovered them dead in their sleeping bags inside a slashed-open tent. The victims, Lollie Winans and Julie Williams, were a young couple on a week-long backcountry trek. After five long years, a suspect was finally indicted. But due to contradictory DNA evidence, the case against him was quietly dismissed. More years passed, and the investigation was still stalled when Miles—an Outside contributor, avid hiker, and, like Winans, an alumna of Maine’s Unity College—became obsessed with the case. “The truth was,” she writes, “I had become feverish, if not altogether frantic, in my attempts to advance the case.” Miles ultimately comes to believe the likely perpetrator was a serial killer who had already died in jail. But her zeal in finding justice for Winans and Williams is welcome in a world where lesbian couples still face violence in the wild, most recently the murders of two women in a campground outside Moab, Utah, in 2021. As John Grisham writes in a blurb on Trailed’s back cover, “The truth is still buried. I couldn’t put it down.”

The Last Chairlift, by John Irving

Fortunately for Outside readers, one of America’s most readable novelists is also a lifelong skier, with two grandchildren on the U.S. Ski Team. So it was with delight that outdoor enthusiasts greeted The Last Chairlift, his 15th novel, his first in seven years, and what he says will be the last of his major works. For Irving fans, the book brings plenty of his trademark empathy, accidental death, sexual politics, and haunted family dynamics. In this case the ghosts are literal, at Aspen’s Hotel Jerome, where the main character decamps to try to understand his mother, a ski racer who got pregnant with him as a teenager. Some critics have called The Last Chairlift a bit overstuffed. But when you’re snowed at a ski lodge this winter, what’s another 900 delicious pages?

Shutter: A Novel, by Ramona Emerson

What’s a police thriller set in Albuquerque doing on this list? It’s a departure from the usual outdoor canon but a fun one, a companion to the recent Indigenous stories being told on screen, from Hulu’s Reservation Dogs to the AMC series Dark Winds, which follows writer Tony Hillerman’s Navajo detectives Leaphorn and Chee. In this gritty thriller, which was long listed for the National Book Award, forensic photographer Rita Todacheeneis haunted by ghosts. They appear to her at crime scenes, demanding that their deaths be avenged, and at her grandmother’s house back on the Navajo Nation, whose wide desert skies Rita misses deeply. Emerson, who is herself Diné and a former forensic photographer, is also an Emmy-nominated documentary filmmaker. “I was drawn to make films about my community because those stories weren’t being told,” Emerson has said. “More importantly, if they were being told, they were being told by people outside of our communities.”

Dinosaurs: A Novel, by Lydia Millet

Just about every year, it seems, novelist Lydia Millet comes out with another sharp, slim masterpiece of climate fiction. In 2020, it was The Children’s Bible; this year it’s Dinosaurs, both finalists for the National Book Award. In this, her 13th novel, wealthy New Yorker Gil decides he’s done with the city; he chooses to move to Arizona based on some drone footage of the desert. “But he wanted to feel the distance in his bones and skin,” Millet writes, “the ground beneath his feet. Not step onto a plane and land in five hours after a whiskey and a nap.” So he walks, the whole way, for five months. But the the narrative picks up after that, once he arrives in the suburbs of Phoenix. The action here is much more interior, from Gil’s relationship with the neighbors in their glass house to the birds disappearing in their neighborhood. Millet, who still holds down her day job at the Center for Biological Diversity in Tucson, is one of the smartest minds around, an insistent voice on our responsibilities as humans in the larger world.

An Immense World: How Animal Senses Reveal the Hidden Realms Around Us, by Ed Yong

Did you know that leopard urine smells like popcorn, and stressed-out frogs can smell like peanut butter or curry? These wonders merely scratch the surface of Ed Yong’s marvelous look (sniff?) at the sensory experiences of animals. Yong, a British-American science journalist who won a Pulitzer Prize for his work in the Atlantic, has emerged as one of our brightest science writers. His first book, I Contain Multitudes: The Microbes Within Us and a Grander View of Life, looked at the universe inside the human body. This one looks outward, at our fellow creatures. And while it compiles enough amazing information that your loved ones will ask you to stop reading factoids aloud, that’s not the point. “When we pay attention to other animals,” writes Yong, “our own world expands and deepens.” Given how myopic humans can be, there is great value in walking in someone else’s paws for once. “Some scientists study the senses of other animals to better understand ourselves,” Yong writes. “Others reverse-engineer animal senses to create new technologies…. I’m not interested in either. Animals are not just stand-ins for humans or fodder for brainstorming sessions. They have worth in themselves.” Rarely has it been more evident than here.

Embrace Fearlessly the Burning World, by Barry Lopez

Perhaps no one has paid more patient attention, as he himself puts it, to the beautiful immensity of life on earth than Barry Lopez. This collection is his last, published posthumously after his death from cancer on Christmas Day 2020. Many of these essays have appeared before, in literary magazines like Granta and Harper’s, particularly the wrenching “Sliver of Sky,” about the sexual abuse he experienced as a child. But others are unpublished, and their arrangement paints, as he writes here about Wallace Stegner, “the measure of a life.” In Lopez’s case, that life took him from Antactica to the Yukon and ultimately to the banks of Oregon’s McKenzie River, his home base for 50 years. It’s a heartbreaking sort of foreshadowing to read his descriptions of those lush woods, knowing that in the fall of 2020, just months before his death, the Holiday Farm Fire claimed 17o,000 acres of that forest. Lopez’s home, he wrote on Facebook, was “damaged but still standing.” (Like so many of us today.) All of this may sound like a bit of a downer, but believe me, it’s not. “The central project of my adult life as a writer,” Lopez writes, “is to know and love what we have been given, and to urge others to do the same.” He warns us not to “give in to the temptation to despair.”

Source link