No products in the cart.

Outdoor Adventure

The 11 Mental Skills That Make an Athlete Elite

Get full access to Outside Learn, our online education hub featuring in-depth fitness, nutrition, and adventure courses and more than 2,000 instructional videos when you

sign up for Outside+.

Earlier this year, I wrote about a Swiss study that suggested (with apologies to Yogi Berra) that cycling up a mountain is 77 percent physical and 23 percent mental. There are plenty of reasons to take those particular numbers with a big grain of salt, but one in particular stuck out to me: there’s no universal agreement on which mental traits or skills contribute to athletic success. The Swiss study used questionnaires to assess five potential psychological factors including mental toughness and self-compassion. But what else might they have been missing?

That’s essentially the question that underlies an ambitious new paper in the Journal of Applied Sport Psychology (free to read here). Back in 2019, a Canadian non-profit called Own the Podium, whose mission is to propel Canadian athletes to Olympic medals, assembled a group of six elite sports psychologists to come up with what they dubbed “The Gold Medal Profile for Sport Psychology,” or GMP-SP. Their mission was to synthesize the vast and expanding literature on sports psychology and create a definitive list of what mental skills separate the good from the great, and how to develop them.

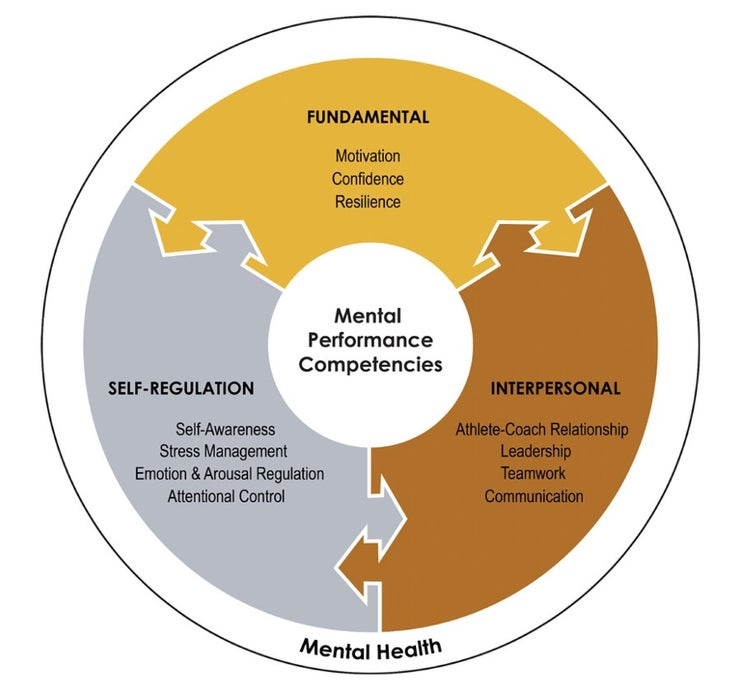

The new paper is a condensed version of the document that the group, led by Natalie Durand-Bush of the University of Ottawa, presented to Canadian sports governing bodies in 2020. It lists 11 “mental performance competencies” divided into three categories, which all contribute to maximizing athletic performance and maintaining mental health. It’s by no means the first attempt to sum up the psychological ingredients of peak performance, but the field continues to evolve: the GMP-SP is the first to incorporate mental health as an explicit goal, and it includes traits such as resilience that have gotten lots of research attention in recent years.

Without further ado, here’s the graphical version of the GMP-SP, showing the three categories and 11 competencies along with plenty of arrows and deep geometric symbolism:

The first category, colored gold because it’s the most important, contains the fundamental competencies that underlie all the other ones:

- Motivation: The importance of motivation is fairly obvious, and indeed studies like this one have found that, for example, among fencers and long-distance runners those who are more highly motivated are willing to train harder and end up achieving higher performance levels. But not all types of motivation are equivalent: intrinsic motivation is, in many contexts, more durable than extrinsic motivation.

- Confidence: I can’t help thinking of Eliud Kipchoge’s response when he was asked how he would approach the “impossible” task of running a sub-two-hour marathon: “The difference only is thinking,” he said. “You think it’s impossible, I think it’s possible.” Numerous studies have linked what sports psychologists call self-efficacy—your belief in your capacity to do what’s needed to achieve a given performance—with athletic success. There’s a bit of a chicken-and-egg question here, but on balance it seems clear that greater confidence predisposes you to success.

- Resilience: Let’s pick another Kipchoge example, since he’s the current paradigm of a mentally strong athlete: in the 2015 Berlin Marathon, the insoles of his shoes started sliding out before he hit the halfway mark of the race. He still won, insoles flapping in the breeze like mini-wings, in one of the fastest times ever recorded. In sport, as in life, things go wrong, and you need to be able to bounce back from setbacks without flinching.

The second (silver) category is self-regulation. Think of sport as a giant Marshmallow Test, both in the immediate crucible of competition and in the broader picture of adhering to a rigorous training plan rather than vegging on the sofa. These are the ingredients you need:

- Self-awareness: To manage stress, regulate emotion, and focus your attention (the other three skills in this category), you first need to be able to recognize what your current psychological state is, and what it needs to be when you’re in the zone. G.I. Joe was right: knowing is half the battle.

- Stress management: Trying to win the Olympics is stressful. There may be some things you can do to mitigate some of those stresses, like flying first-class to make frequent travel less of a burden. But what we’re really talking about here is how you respond to those inevitable stresses. Do you view the butterflies in your stomach before a race as a sign that you’re scared, or a sign that you’re excited?

- Emotion and arousal regulation: Exactly how many butterflies should there be in your stomach before a race? There’s no right answer. Instead, sports psychologists talk about “individual zones of optimal functioning.” Some people perform better at higher levels of arousal than others; and the same person might need different levels in different contexts. Wherever your sweet spot is, you need tools—it could be something as simple as deep breathing—to turn the dial up or down.

- Attentional control: To perform well, you need to be able to focus on the right things. What are the right things? That depends. Focusing on your running form can make you run less efficiently, and more generally having an external focus is better for learning and performing physical movements. But to run a good marathon, you need to be highly attentive to your internal state: how your breathing feels, how your legs are doing, and so on. In other words, you need to be able to adjust your focus depending on the context, while filtering out everything else that’s trying to distract you.

The final (bronze) category is interpersonal competencies, which involves your dealings with other people. Its relevance is obvious in team sports, but it also applies in individual sports to your dealings with coaches and training partners (and, for elite athletes, with therapists and sponsors and administrators and so on). The four competencies are athlete-coach relationship, leadership, teamwork, and communication. They’re all important, but there’s nothing particularly surprising to say about them.

Putting this all together, Durand-Bush and her colleagues include a simple rubric to evaluate how an athlete is doing in these 11 competencies. For each one, the athlete gives herself a rating from one (novice) to three (advanced); the coach or sport psychologist does the same. Then they add any brief observations, recommended strategies for getting to the next level, and a ranking of how high the priority is. Completing this assessment periodically gives you a sense of where you’re falling short of gold-medal characteristics, and how well you’re closing the gaps.

There are a few interesting omissions in the framework. Some of the most familiar sports-psych tools, like goal-setting, imagery, and self-talk, aren’t included. These are all classified as “subsidiary competencies,” which can be harnessed in support of the 11 chosen ones. Motivational self-talk (“You can do this!”) can boost motivation and confidence; procedural self-talk (“Follow through with the wrist”) can help direct attentional control. The authors also note some sport- or domain-specific skills: decision-making for team sports, pain management in endurance sports, fear management in speed sports, creativity in aesthetic sports.

I think it’s fair to say that this is unlikely to be the final answer to the question of what it takes, psychologically speaking, to own the podium. But it’s an interesting starting point. Many of these traits can be quantified with validated psychological questionnaires. What happens if you give these questionnaires to a bunch of developing athletes, then wait a few years to see who is successful? How much, if anything, can this framework predict? I don’t know the answer—but just for the record, Canada matched its best-ever medal haul (excluding the boycotted 1984 Games) at last year’s Summer Olympics, and its second-best haul at this year’s Winter Games.

Hat tip to Chris Yates for additional research. For more Sweat Science, join me on Twitter and Facebook, sign up for the email newsletter, and check out my book Endure: Mind, Body, and the Curiously Elastic Limits of Human Performance.