No products in the cart.

Outdoor Adventure

The Science Says a Sub-Seven-Hour Ironman Is (Sort of) Possible

On June 5, four of the world’s greatest long-distance triathletes will take aim at a couple of those round-number barriers we love to obsess about. There’s the four-minute mile, the two-hour marathon… and now, the seven-hour (for men) and eight-hour (for women) Ironman-distance triathlons.

The catchily named Pho3nix Sub7 and Sub8 Powered by Zwift races are explicitly modeled on Eliud Kipchoge’s two-hour marathon events. Like Kipchoge’s races, they’re funded by an enthusiastic billionaire (in this case the Polish businessman Sebastian Kulczyk, through his foundation promoting kids’ fitness). They’ll take place on a specially designed course with tweaked race rules allowing a bunch of pacemakers. And like the original Breaking2 race, the initial reaction from knowledgeable observers was that the goal is probably out of reach.

In anticipation of the attempt, pro triathlete Antoine Jolicoeur Desroches, a sports science doctoral student at the University of Sherbrooke, along with his supervisor Éric Goulet, has published a preprint (meaning an article submitted to an academic journal but not yet peer-reviewed) assessing whether a sub-7 Ironman is possible, and if not, how much external assistance (like pacing) would be required to close the gap. He started out as a skeptic, but as the final details of the attempt have been revealed, he’s come around to believing that it might be possible. Here’s why:

The Backstory

It’s likely that you haven’t spent many nights lying awake and wondering whether humans would ever crack the seven-hour Ironman barrier. The focus in triathlons has always been more on head-to-head competition rather than time. I suspect that’s largely because it’s so difficult to compare times on different bike courses. In Olympic-distance triathlons, drafting is permitted, which means that times are even more context-dependent. Drafting on the bike isn’t permitted in Ironmans, but it’s hard to compare the topography and prevailing weather conditions on courses around the world.

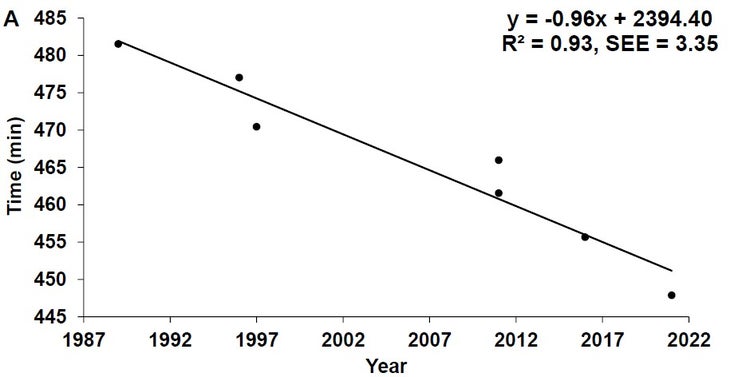

Still, records are kept. Over the Ironman distance of 2.4-mile swim, 112-mile bike, and 26.2-mile run, the record set in the inaugural race in 1978 was 11:46:58, and the first women’s record of 12:55:38 was set a year later. The records have steadily dropped to 7:27:53, set by Jan Frodeno in 2021, and 8:18:13, set by Chrissie Wellington in 2011. Reigning Olympic champion Kristian Blummenfelt also managed a 7:21:12 last year, but the swim was current-assisted so isn’t recognized as a record. Here’s a graph of the progression of the men’s record, from Desroches’s paper (which unfortunately focuses only on the men’s side):

If you extend that straight line, you find that the current trend predicts a sub-7 Ironman in 2049. That’s a long time from now.

To assess how feasible the challenge is, you can also add up the fastest-ever individual legs in official competition: Jan Sibbersen’s 42:17 swim, Jan Frodeno’s 3:55:22 bike, and Gustav Iden’s 2:34:50 marathon. The total of 7:12:29 gives you a sense of just how big a challenge sub-7 is. Another indication: the half-Ironman record, held by Blummenfelt, currently stands at 3:29:04: almost exactly the pace required for a sub-7. Given the typical half-to-full slowdown of 7.3 percent seen in elite long-course triathletes, you’d expect that to translate to a 7:24:58, which is very close to Blummenfelt’s current-assisted time.

The bottom line: it’s not going to happen in an ordinary race. And indeed, the Ironman World Championships, delayed from last year, were held earlier this month. The winners were Blummenfelt in 7:49:16, while Swiss star Daniela Ryf won the women’s race in 8:34:59.

What It Would Take

Desroches and Goulet break down the barriers and opportunities for improvement in each of the three disciplines. There are some unique individual considerations: wetsuits in swimming, bike technology in cycling, shoes in running. And then there’s drafting, which is relevant in all three disciplines. It quickly becomes clear that the barriers are only plausible if (unlike in official Ironman competition) drafting is permitted—which it will be in the Pho3nix race.

It’s well known that drafting is way more important in cycling than running because the speeds are so much higher. Swimming is even slower than running, but drafting can still make a substantial difference because water creates more drag than air. The researchers cite previous estimates that drafting can reduce energy expenditure by 5 to 10 percent, or increase speed (at a given level of energy expenditure) by 3.2 to 6.9 percent. I’d take those numbers with a big grain of salt, because they came from very short 400-meter swim trials. Still, if you take the most optimistic estimate, you’re looking at a potential savings of about three minutes over 2.4 miles.

Thanks to all the debates about the Breaking2 marathon project, there’s been plenty of attention devoted to the time savings of drafting in a marathon. At two-hour pace, estimates varied from about one to six minutes. At the slower pace on the last leg of a triathlon, drafting will be less beneficial. Desroches’s guess is that the savings will likely be between one and two minutes.

To shave 28 minutes off Frodeno’s record, two minutes on the swim and three minutes on the run leaves an awful lot of work to be done on the bike. Fortunately, that’s by far the longest leg, typically contributing more than half of the overall time, and it’s also the leg where drafting will help the most. In team pursuit formation, the third and fourth riders in the line reduce their drag by 55 and 57 percent respectively. That’s a big deal, because cyclists spend as much as 90 percent of their energy overcoming air resistance at high speeds.

If you run some numbers, things get interesting. With generic parameters for weight, frontal area, drag coefficient, and so on, you can estimate that a hypothetical cyclist would have to put out 300 watts to ride a 112-mile bike leg in roughly four hours. If, as Desroches estimates, he could reduce his power output by up to 40 percent by drafting, this suggests that he could ride at the equivalent of 500 watts (while actually only putting out 300 watts), and finish the leg in 3:19, saving about 40 minutes. Now we’re talking.

In a sense, this becomes reminiscent of the Breaking2 project, where calculations that included drafting, the effects of the new Vaporfly shoes, and various other potential time savings suggested that Kipchoge should be able to run a ludicrous time like 1:54. Reality, however, doesn’t always conform to our pie-in-the-sky calculations. Even the best cyclists won’t be able to maintain anything close to perfect team pursuit formation for 112 miles, so the actual savings will be substantially less than 40 minutes.

Desroches and Goulet also spend some time analyzing other factors like course design, and they come up with some interesting suggestions: find a place with calm saltwater, low temperature, and low humidity, like Bahrain, for example. Start the race late enough in the day that the sun sets as the marathon starts, since the optimal temperature is warmer for cycling than running. Optimize the altitude and gradient and the turns and so on. But the takeaway, at least from my perspective, is that we’re only having this conversation because there’s a huge potential savings from drafting on the bike.

The Plan

That’s the theory. In practice, the race is going to go down on either June 5 or 6 (depending on the weather) at the Dekra Lausitzring, a race track in Germany. The altitude is just 380 feet, and the expected temperature will be between 53 and 73 degrees Fahrenheit. The course will start with a one-way swim across the calm waters of Lake Senftenberg, followed by a ten-mile ride (dropping 88 feet) to the race course, where they’ll do 3.6-mile loops on the bike and 2.2-mile loops for the run.

The two male contenders are Blummenfelt and Alistair Brownlee, the two-time Olympic champion from Britain. The female contenders are Swiss two-time Olympic medalist Nicola Spirig and Britain’s Katrina Matthews, the silver medalist at Worlds earlier this month.

Interestingly, unlike the centrally planned approach of the Breaking2 race, each of the four contenders is assembling their own support team and making their own tactical decisions. The key constraint: they are each allowed to bring ten pacemakers, who they can deploy however they please in the three events. During running and biking, the pacemakers can substitute in and out; during swimming (by my reading of the rules), any pacemakers have to start with the competitors, and once they drop out they can’t rejoin the race.

One other detail I noticed: the competitors are allowed to wear any wetsuit they want, with no limitation on thickness, in contrast to the five-millimeter limit in official Ironman races. Desroches notes research that found a 6 percent boost in swimming speed with a wetsuit thanks to its buoyancy, but he doesn’t think added thickness will provide much further benefit. There may be other nuances in the rules that I’ve missed, leaving the door open for surprises to be revealed on the day of the race.

The bottom line: it’s not out of the realm of possibility for the men, and the same arguments apply to the women’s race, where the current gap is a more modest 18 minutes. In a sense, having looked through Desroches and Goulet’s analysis, success in either race would be less surprising than either of Kipchoge’s runs were. Few people thought that drafting mattered in marathons, or that springy shoes could make a big difference; in contrast, everyone already knows that drafting is a big deal in cycling. Still, there’s a huge gap between recognizing that drafting matters and believing that one of those four athletes will make the leap to breaking seven or eight hours—enough of a gap, perhaps, to entice you to tune into the free 9.5-hour live broadcast.

For more Sweat Science, join me on Twitter and Facebook, sign up for the email newsletter, and check out my book Endure: Mind, Body, and the Curiously Elastic Limits of Human Performance.