No products in the cart.

Outdoor Adventure

The Storm King Memorial Trail Honors Fallen Firefighters

May 2024

This time when I see the first tree hung with the blowing, ragged shirts, the sight is more familiar, less stark than before. I am more prepared.

Hiking the Storm King Mountain Memorial Trail, near Glenwood Springs, Colorado, my son Ted and I approach another tree, this one with firefighter helmets at its base.

In the wildfire of 1994, the ridge we’re on was the dividing line between the firefighters who lived or did not: those who escaped over the other side or those who were caught as they labored uphill, not knowing that the fire behind them would move upward at speeds up to 35 feet per second. There had not been a similar wildland-firefighter disaster since the loss of 13 in Mann Gulch, Montana, 45 years before.

Ted and I look around, west at the wide valley spreading out from the sinuous Colorado River, the fluted edges of Hogback Ridge to the south catching evening light. At the end of May, the slopes around us have just changed from the light green of spring into fresh early-summer emerald.

It is a hot day, and we stand in the breeze in a saddle beneath the 8,797-foot apex of the ridge; the same saddle the survivors attained in 1994 is the hike’s destination. “This wind is heavenly,” I say.

“It would be bad for firefighters,” Ted responds. “It’s really beautiful here,” he says, turning to me with a faint grimace.

Unspeakable tragedy happened in this spot. The beauty is no justification, but a solace, a benediction.

From here, the trail descends along the fire break the firefighters battled to establish, and then loops back to rejoin the approach. We start down the loose, gravelly trail, toward the first cross.

July 1994

1994 was a drought year. On Saturday, July 2, an intense thunderstorm roared in from the west, and lightning struck a tree on a major ridge of Storm King Mountain, five miles west of Glenwood Springs. The next morning a tendril of smoke showed, visible from the adjacent I-70, and was reported by many. That day the fire was named the South Canyon Fire, but it was on Storm King Mountain, off the Canyon Creek turnoff; like many, I just call it the Storm King Fire.

Accidents in mountaineering and aviation and hospitals are often caused not by one error or element, but a series, in what is often referred to as the Swiss Cheese Model of causation. Various factors, each of which can be represented as a layer of cheese, and each of which could have altered the course of events, line up. Elements that affected or might in some way have prevented the accident are holes that, unfortunately, align.

A day after the fire started, over three dozen lightning-sparked fires were burning in the encompassing Grand Junction District, managed by the Bureau of Land Management (BLM). As days passed with agencies spread thin, major resources were diverted to the largest fire, in Paonia, 70 miles from Glenwood Springs, which burned three houses. I live in Carbondale, 12 miles from Glenwood and 58 from Paonia; we smelled the smoke, and ashes flecked our neighbors’ trampoline.

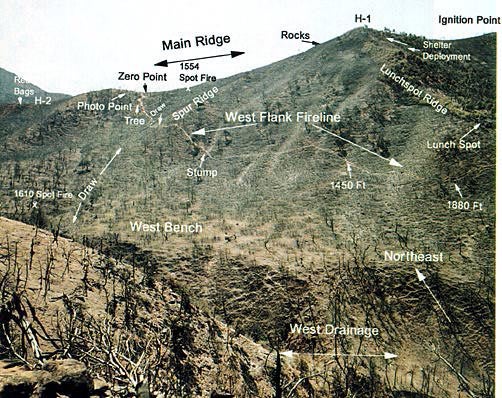

On July 4, three crew members from the White River National Forest carried chainsaws up Storm King mountain and made assessments. The next day, July 5, seven BLM and Forest Service firefighters hiked up to the fire, located on what is known as the Main Ridge (or Hell’s Gate Ridge). Crew members cut a helicopter landing spot (called H1) and an air tanker dropped retardant.

According to the 250-page investigation report prepared by the South Canyon Fire lnteragency Investigation Team for the Chief of the Forest Service and the Director of the BLM, at 5:30 p.m. the first crew left for equipment changes, and at 5:45 p.m., eight smoke jumpers parachuted in above the fire. On July 6, more firefighters arrived, putting 49 on the mountain by the afternoon. The report states that 16 smokejumpers, 20 hotshots, a six-person helitack crew (two at the fire and four at the helibase), and 12 BLM/Forest Service firefighters (ll at the fire, one at the helibase) were assigned to the fire.

That afternoon a helicopter dropped water, but after a cold front moved in at 3:00 p.m. and the winds picked up, drops became ineffective.

The same day, July 6, 1994, I was walking 10-month-old Teddy around town in his stroller. I remember the day as bright and hot, and looking up thinking, Where’d that wind come from? It was blowing, and the undersides of nearby tree leaves turned up, glinting.

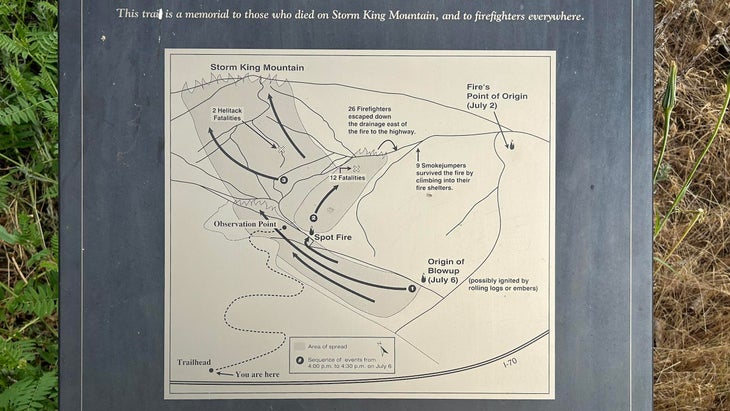

That was the day the fire on the Main Ridge of Storm King spread, likely by lofted burning embers, down into the adjacent West Drainage and then moved rapidly up that narrow canyon and east to the Main Ridge.

I wheeled Teddy home. That evening our friend and employer Michael Kennedy, then owner of Climbing magazine, called saying that 14 firefighters had been killed on Storm King.

July 2001

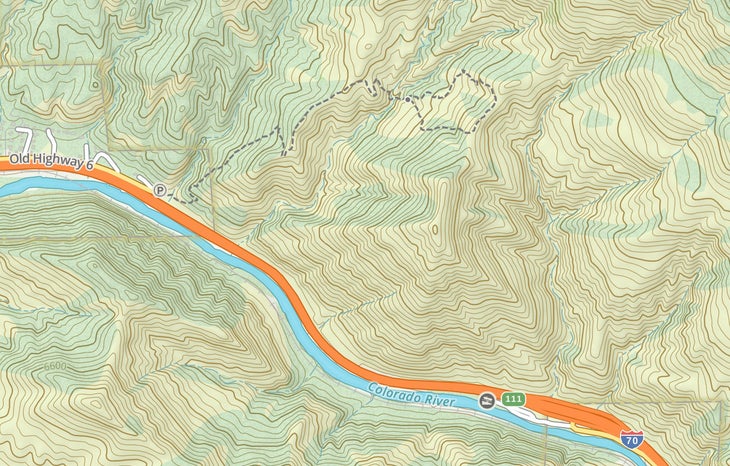

Ted and I have hiked Storm King twice before. In 2001, my sister Lucy and I took our boys partway up when Teddy (what we called him when he was younger) and his brother, Roy, were seven and four, and her son, Sam, was eight months old. The trailhead is just off I-70, where it runs alongside the Colorado River. We carried the younger kids in backpacks, and Teddy walked.

The memorial trail first began as a path made by family and friends, and over ensuing months was improved by the BLM, Forest Service, Air Force cadets, and 100-plus volunteers as a tribute to the 14 who lost their lives—and firefighters everywhere.

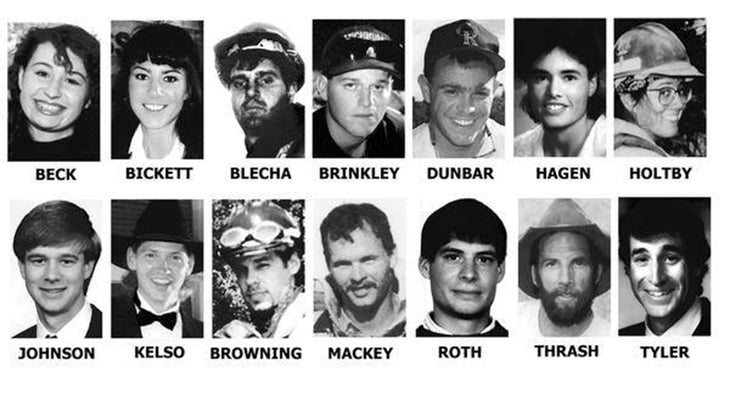

Nine of the lost were from the 20-person Prineville Hotshot Team from Oregon: Kathi Walsleben Beck, 24, Tamera Jean Bickett, 25, Scott Alan Blecha, 27, Levi Brinkley, 22, Douglas Michael Dunbar, 22, Terri Ann Hagan, 28, Bonnie Jean Holtby, 21, Rob Johnson, 26, and Jon R. Kelso, 27. Four of the five women on the Prineville team were killed. Three of the deceased were smokejumpers, who parachuted in: Don Mackey, 34, Roger Roth, 30, and Jim Thrash, 44, and two were helitack crew (meaning they were transported by helicopter): Richard Kent Tyler, 33, and Robert E. Browning, Jr., 27.

The roundtrip hike is only four miles, but steep, rising 1,500 feet. As my sister, the children, and I started out, we stopped and read the excellent interpretive signs—giving the firefighters’ names and faces, different maps, and other information—at the trailhead, then started up the path, deliberately left rough as a reminder of the conditions firefighters face, 700 feet to a minor ridgeline looking over at the Main Ridge.

We peered into the drainage east of us, where the fire had ascended, and then we all dipped slightly down the hillside to an observation platform, with more plaques and a wide view. I had read Fire on the Mountain, the meticulously researched account of the tragedy by John N. Maclean (son of Norman Maclean, who wrote Young Men and Fire about the 1949 Mann Gulch disaster), but the visuals and signage here showed me something I’d never understood: where on the rib opposite us one group of firefighters had escaped to previously burned terrain, deployed their fire shelters, and lived.

Other visitors had stopped at the observation point, unwilling or unable to continue the steepening second half of the trail, some leaving messages and flowers. Teddy knelt by a potted African violet, opened his Nalgene bottle, and watered it. That was as far as our young party could go, too, and we turned around and descended.

June 2004

The South Canyon Fire and what happened is important history in the area, and I’d heard from a couple of local friends that I should go, in part to see the mementos brought here in tribute. Three years after that first, partial hike, when I thought both Teddy and Roy, aged 10 and seven, could make the full ascent, I brought them and two of their friends the same age.

At the trailhead, we looked at images of each of the men’s and women’s faces, read out their names, and talked about some of them. One, Levi Brinkley, was a triplet. Two others—Roger Roth and Terri Hagen—were from the Iroquois Nation. I knew that one firefighter, Kathi Beck, had a subscription to Climbing, where I was an editor at the time, giving me a small sense of connection to her.

The five of us proceeded, with breaks and snacks, to the observation point, crossed the gully, and hiked up the other side. At the Main Ridge we saw the T-shirts, left by others as remembrances and in solidarity, tied on trees, then reached the vantage point where the photos I’d studied so often in the book had been taken. There, two firefighters, Sarah Doehring and Sunny Archuleta, pulled out a camera and took a few pictures at the top of the ridge. Archuleta saw the fire advancing toward the other firefighters, and realized disaster loomed. He knew that documentation would be crucial to later study.

The west-flank crew on the fireline, 13 of them, approached the ridge in a line on the last rise. The terrain is uneven, rolling, and they could not see what was coming up behind them. I’ve always remembered how they carried packs, chainsaws, and water, not realizing they should drop them to increase their speed; the fire must have still seemed some distance off. Between 4:14 p.m. and 4:18 p.m. the fire spread below the west flank of the ridge. The wind whipped the flames into a “blowup” (a “sudden increase in fireline intensity or rate of spread,” according to the USDA, often involving violent convection) racing up the drainage in two minutes. The fire caught the west-flank crew on the final 300-foot rise, a stone’s throw from safety on the other side.

Two other firefighters, Brad Haugh and Kevin Erickson, who had waited by a tree (subsequently referred to in accounts as The Tree) 200 feet below the ridgeline to encourage the crew on the way up, had to flee, receiving first- and second-degree burns respectively.

Only one of the west-flank crew, Eric Hipke, made it to the ridge, but with his fingers badly burned and burns elsewhere. From there, he escaped down the eastern drainage with help from Erickson and Haugh. Scott Blecha was found only about 100 feet below the ridge. The rest were engulfed closely grouped together 200 to 280 feet below. A few had deployed their shelters.

Browning and Tyler, on the helitack crew, were last seen on the ridge jogging upwards, heading northwest, possibly toward a flat outcropping, but were caught by the fire. Eight others to the south fled up toward a helicopter landing spot on higher terrain on the Main Ridge, deploying their shelters 100 and 200 yards below it. They survived.

As we reached the Main Ridge that day in 2004, Teddy said, “Let’s all take off our hats.”

We started carefully down the loose slope, me in the rear, searching for the memorials below. “A cross!” the boys called out, coming to Scott Blecha’s, so painfully close to the top. We looked at flags, medals, beads, and hats left there for him, then descended, the boys calling out to come upon each cross, and reading each firefighter’s name aloud. Names. As my life proceeds, I have found names more and more important; speaking them to be an honor. We brushed the red dust off little treasures and marveled at pocket knives, badges, always more hats, empty bottles of favorite beer. We gently opened an enamel box to find a guitar pick, then closed it again.

On the way home, I asked the boys what they learned. Teddy said people should communicate, and his friend Carson said, “That nature is powerful, and to pay attention.” I need to remember that myself.

June 2024

As I write, it’s fire season, with two devastating blazes in New Mexico and another in Southern California. I’ve already seen two small wildfires where I live, heard the sirens; seen posts about fires along nearby highway 70; known, as ever, to be grateful when it rains. I often think of what the Storm King crew went through and what the young crews fighting fires endure today. Outside has published stories about many wildfires, including Torched, about smokejumpers across the West, in 1997, and 19: The True Story of the Yarnell Hill Fire, investigating the deadliest fire in the U.S., in 2013.

A few days before my most recent hike with Ted, I looked through Fire on the Mountain again, gazed at the faces of the ten men and four women, most in their twenties. Wildland firefighting is an exhausting job often done by students or youth with seasonal work.

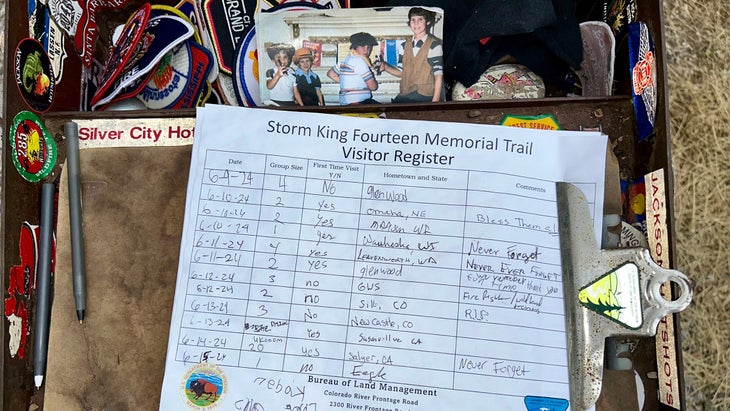

At the trailhead a metal box contains a visitor register and many dozen custom patches and stickers, left by hundreds of visiting firefighters. In it is a photo of a young Jon Kelso, labeled as “entertaining his cousins,” ages four to 15.

We start up the first section, and Ted stops partway to wait for me. “They were just young men and women drawn to adventure,” he says when I join him.

Cicadas chirr, my trekking poles click. I smell sage.

Ted has grown up. He’s now 30 years old. This year he moved in with his partner, Aisha, and—after years in finance and much thought—recently bought a longtime area guiding and horseback company, Capitol Peak Outfitters, in Old Snowmass, near Aspen. He has been hunting with his father since age five and knows more about the woods than I do.

We step over an oval of scat in the trail. “Coyote,” he says.

“How do you know?”

“By the hair in it, and the shape.” He nudges it with his toe. “Sometimes you can see bones in there.”

The air is dusty and hot, with temps in the 80s and the sun blasting the sandy slopes, and I keep coughing, dry little barks.

“Is that cough from the thyroid cancer?” he asks.

That was eight years ago. So many things have happened in 30 years. In 1994, his brother hadn’t even been born.

After my father (for whom Ted is named) died, suddenly and at only 54, my mother sometimes said: “I feel so bad for him. He’s missing everything.” I keep thinking of the 14 firefighters who have missed everything in these years.

Higher, we make out the marble crosses, always a poignant sight, and the still-maintained fireline. We cross the drainage and begin the final ascent.

Birds sing and, using an app, Ted identifies the spotted towhee and evening grosbeak. Lizards scuttle in our path.

We traverse the ridgeline, stopping to read a plaque, festooned with flags, bracelets, and beads, marking the helitack crew sites. An empty green bottle flanks the stanchion. “Jagermeister,” Ted says with a chuckle. We pass a flat red rock covered in ten firefighter medals. Finely wrought belt buckles from other squads line another stand.

Moments further, I tell Ted, “This is where they took the pictures.” I gaze down, remembering the images, taken from this spot, of the landscape and fire line.

Often over the years, I have thought of the dilemma of Hipke, the sole survivor of the west-flank group. Third in line on the way to the ridge and feeling urgent as the crew evacuated along the fireline, he thought of hurrying around the two people in front of him but out of decency hesitated. When they paused, however, one saying the word, “shelter,” he ran through, in the last seconds hurling himself over the top of the ridge.

A report on coloradofirecamp.com reads: “We estimate that after a short hesitation, Hotshot [Scott] Blecha stepped around the group, and continued up the hill. Our timeline places Hipke about 45 seconds behind [Kevin] Erickson [who had waited at The Tree]. We estimate that Blecha followed about 40 seconds (100 feet) behind Hipke.”

Hipke has since made a documentary film, which came out ten years ago, called “1994 South Canyon Fire on Storm King Mountain.”

At the first cross, Ted and I feel a fresh rush of sorrow.

“Scott was trying so hard,” Ted says. “Think if you gave it everything you had, and you were so exhausted. And it was so hot.”

Jim Thrash is next. We read all the names, stop at every one. Some of the crosses are so close together. More mementos—chainsaw chains, pocket knives, dreamcatchers. Skis: for Levi Brinkley, the triplet. The skis have been here since the first time I hiked the trail.

I remembered that Jon Kelso was found beside Terri Hagen, to whom he had once been engaged. Around his cross’s arm a chainsaw chain is rusted fast.

So many ball caps. Some newish, some tattered. “This one has lichen!” Ted says, turning over a white brim with delicate orange-rust patches. A foot-tall dreamcatcher hovers above Terri.

We find the cross for Don Mackey, who had reached safety but circled down to warn his crew, and brought up the rear, with Bonnie Holtby, a third-generation firefighter. “Traps,” Ted says, pointing to the rusted iron teeth, and I suddenly remember the boys identifying those hunting traps last time.

Last time, though I knew Bonnie’s cross was here, I was bewildered to have trouble finding it, but it was overgrown by a bush. That has been cleared. Ted reads aloud from the words scratched into her father’s own helmet: ”This hard hat is left in memory of our daughter, Bonnie Jean… Here in respect to Bonnie, where she gave her life on the line.”

At 21, she was the youngest of the lost.

All this area was once black, and now it’s green. Full regrowth takes 100 years.

We begin our descent, cross the gully. “Look!” Ted says. “A bear!” I have difficulty spotting it, then pick out the roly-poly cinnamon body just before it trundles into the thick oak below the lowest point of the fire line.

“It’s probably a boar,” he says.

“How do you know?”

“No cub.” He adds: “It covered that hillside in about two minutes. Put its snout down and just went through that tangled scrub oak.”

I often recommend the memorial hike and experience to visitors. No one has ever taken me up on the idea except my brother. He understood the hike and returned reverent.

In the car, Ted says, “It’s very tragic, but going there is not horrible, because of all the respect shown by the other firefighters.”

Many lessons were learned, too (see video below)—such as for firefighters to become situationally aware of terrain, vegetation and weather (and to be included in briefings and able to speak up more); for managers to have intimate knowledge of terrain and conditions; for weather warnings to be communicated to those on site; and for better cooperation and coordination between agencies, and better communications between managers and firefighters. Storm King is considered a turning point in wildland firefighting culture, helping those to come later.

July 6, 2024, marks the 30th anniversary of the Storm King tragedy. Please give the families privacy and refrain from hiking the memorial trail that morning.

The trail is just off I-70, commonly used by people traveling to the Colorado mountains and Utah desert. It is south-facing, better done in spring or autumn than the summer sun, but always a sacred journey. Stay on the trails to protect the hillsides, and bring plenty of water. Go and remember the people, honor them, say their names.

During this fire season, let’s salute and appreciate the people who are on the line trying to keep the rest of us safe.

Watch: Lessons From the Storm King Fire

Alison Osius is a senior editor at Outside magazine and Outside Online. She has lived in Western Colorado since 1988, when she moved to Aspen for a job at Climbing magazine. Now residing in Carbondale, she is an avid climber, hiker, and skier. She can be reached at aosius@outsideinc.com.

For more by this author, see:

Source link