No products in the cart.

Outdoor Adventure

The Titan Disaster Shouldn’t Keep Us Away from the Ocean Floor

By the time we’d reached the bottom of the Cayman Trench, some 2,000 feet below the ocean’s surface, I’d lost feeling in my legs. My neck was aching, and my ears felt as though they were going to explode under the mounting pressure. “Heavy,” said the passenger sitting next to me. He stared out the window with shell-shocked eyes, and I looked, too. A Milky Way of multicolored stars twinkled in blue, violet, and white as far as we could see, like fireworks in a night sky. But these were no fireworks, and the view was no starscape.

What we were seeing were the bioluminescent emissions from tens of thousands of plankton, cephalopods, and who knows what else. This is what the world looks like at the ocean’s sunless depths.

I’d come here because I wanted to see where the planet’s largest collection of organisms called home. I wanted to explore one of the last frontiers on earth.

This was more than ten years ago. Back then, regular folk weren’t talking about vacations to the deep ocean, let alone booking trips to it. There were no sanctioned tours or government-licensed operators to take you. The only way for a private citizen like me to get down there was to either save up several million dollars and purchase a custom-built submersible, or fly to Honduras and meet with the renegade undersea explorer Karl Stanley. I chose the second option.

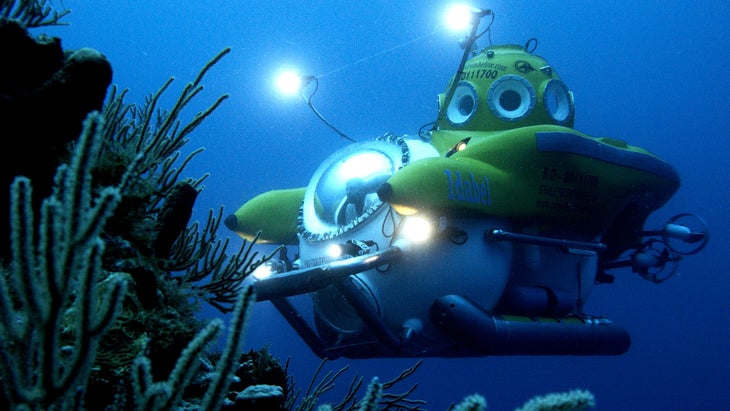

Stanley had hand-built his own submarine, the Idabel, without any formal training and without any government oversight. Because taking tourists down 70 stories in a homemade, unlicensed submarine, without insurance, was a liability nightmare, Stanley moved his operation to Roatan, Honduras, where regulations for underwater craft were lax or nonexistent, and deep water is close to shore. He ran his submarine business off a tiny dock along Roatan’s touristy West End, between a few sand-floored tiki bars serving pink slushy drinks and packs of stray dogs picking through trash heaps.

Stanley had completed more than 2,000 dives in his little homemade sub. Along the way, he had some close calls. Like the one time in an earlier sub when he got stuck in a cave and snagged on a rope. Or another when a window cracked at 1,960 feet as he carried a local from Roatan and the man’s pregnant wife. Dangers aside, thus far Stanley had chalked up more time exploring the deep waters between 1,000 and 2,000 feet than anyone in history.

To join him on a deep-sea adventure, I’d need to autograph no waiver, wear no helmet, strap on no seat belt. I just needed to show up at a dock at the end of a dusty dirt road with several hundred dollars and an empty bladder. I signed up. Soon after, I was 200 stories beneath the ocean, witnessing lifeforms that put Avatar to shame.

Today there are more than 200 private submersibles operating around the world and a dozen companies selling tours to the sunless depths. The deep ocean has finally become accessible to anyone who wants to go there. What could go wrong? Even back then, I knew the answer: just about everything.

A Year After the Titan Disaster

It’s been a year since the world saw exactly how lethal these deep-sea voyages can be. On June 18, 2023, the private submersible Titan launched five men on an expedition to view the wreckage of the Titanic, which is roughly 400 off the coast of Newfoundland. The dive was supposed to take a few hours and reach a depth of more than 12,000 feet. But 105 minutes after the Titan ducked below the waves, it went dark.

The U.S. and Canadian Coast Guards and the U.S. Navy were called in on a frantic search to rescue the passengers, only to discover days later that the Titan had imploded. There were no survivors.

The Titan disaster made international headlines for more than a week. Soon millions of people around the world were talking about submersibles and debating the merits of manned exploration to the ocean’s depths.

On various social media platforms, many people wrote condolences to the families of the deceased passengers. Many more mocked the whole enterprise. I saw people label the passengers “daredevils,” “fools,” “arrogant,” “idiotic,” and worse. Several journalists (rightfully) lambasted media outlets for focusing on the lives of five wealthy men lost at sea while 700 migrants drowned in the Aegean Sea a few days after the Titan was lost. The comments and derisions continue to this day. I should know. I’ve been on the receiving end of some of them.

I’ve since spent a decade praising undersea explorers and arguing the importance of visiting the ocean’s depths. Several people scolded me, explaining how manned deep-sea pursuits were not only dangerous and expensive, but also pointless.

They argued that in the age of robotic drones, cameras, cables, and computers, no human needs to go down there again. We can explore the planet’s secret wonders in HD from the comfort and safety of a climate-controlled office. Why bother boarding a sub? Why go deep?

And so I find myself here, defending the human compulsion to explore. You know, that messy, tactile, anything-can-happen kind of exploration we used to be proud of. The kind that shot us to the moon. That brought us across oceans to new worlds. That led us out of caves.

Without that kind of exploration, a scientist can’t prove theories and a journalist can’t tell rich stories. I’ve learned over the past 20 years, through much trial and error, that the only way to really write about a subject is to know it; the only way to know it is to experience it; and the only way to experience it is to show up.

The road to discovery, I’ve learned, is long and hard and filled with frustration, wandering, and dead ends. It’s expensive and too often feels fruitless. Which is the whole point. I believe that casting a wide net and blindly trying to follow leads is an essential part of the discovery process.

The Merits of Showing Up

Anyone with a computer can view HD virtual tours of the Louvre, the pyramids of Giza, and Pisa’s leaning tower. Yet that kind of tourism hasn’t overtaken our collective desire to experience things in person. Families this summer and last have, in record numbers, chosen to spend weeks on the road and thousands of dollars adventuring to these landmarks in person. Business travel also stormed back as soon as airports reopened, and bars, clubs, and restaurants in many cities have become packed to the gills.

After a few years of lockdown, of experiencing life on Zoom, human beings are flocking to IRL experiences. The metaverse is a failed, desolate wasteland, and virtual cocktail parties have gone the way of Iggy Azalea.

As wasteful, time-consuming, and seemingly pointless as it may seem, even bean counters and glad-handers realized that the best experiences in business, science, journalism—and life in general—can only be had in person. This is what the submarine skeptics seem to be forgetting.

The U.S. Navy submersible Alvin has made more than 5,000 dives in the past five decades at depths below 20,000 feet. While researchers were putzing around the Galápagos Rift in Alvin, they witnessed giant “chemosynthetic” tube worms, the first life-forms ever observed to exist entirely without the need for sunlight—one of the most significant biological discoveries. It was in Alvin that researchers recovered a 1.45 megaton hydrogen bomb that had been lost over the Mediterranean Sea in 1966.

It was in another submersible that scientists caught the first footage of a giant squid—a massive, mythic creature that no human had ever witnessed in the wild before. The list goes on and on, and includes hundreds of supposedly impossible discoveries made during deep and dangerous dives into the ocean. Discoveries that were made by showing up. One sub captain told me that on every dive they discovered something new.

Certainly, the passengers aboard the Titan weren’t on a serious scientific or journalistic mission of discovery. They were on a joyride to see the remains of history’s most famous shipwreck. But they were moved by the compulsion to explore. We can have the debate about how deep a submersible can safely go, which safety precautions should be required, who ought to be trusted to build and captain them. Those are worthy discussions, and there are people above my pay grade who should have them.

I’m not against rules and regulations, either—rather, it’s the idea that we should avoid certain kinds of exploration that irks me. I believe that the only real way to experience life and truly connect with the ineffable, otherworldly wonders of the world is to experience them in person. I learned this valuable lesson in those sunless depths, 2,000 feet below the waves.

The View At the Bottom

A carnival of the bizarre danced outside my porthole ten years ago during that submarine dive in Honduras. We’d just touched down on a sandy dune below 2,000 feet. On the other side of the window, a fish with stumpy legs waddled past another fish covered in brown blotches, yawning with pouty Mick Jagger lips.

Minutes later, a beach-ball-size orb appeared a few inches from the glass—a jellyfish, I think—emitting flashes of bright pink and purple light like some kind of underwater disco ball. First only blue lights flashed, then red, then purple, then yellow, until every color in the spectrum had appeared. After that, all the colors appeared at the same time, and the spectacle was repeated. The hundreds of rows of lights were evenly spaced around the glob. It looked like a cityscape after nightfall. When the lights were red, they looked like the taillights of cars on a freeway; when they were white, they looked like an urban grid as viewed from an airplane thousands of feet above.

Between the lights there was nothing—no visible flesh, nerves, bones, or body. And there it was, this thing, two feet from our faces, at a depth equivalent to twice the height of the Chrysler Building, watching us with its non-eyes, communicating with its non-brain, and dazzling us with its Las Vegas lights.

I realized that not only had no human ever seen these animals, but that these creatures had never seen themselves. The ocean down there was completely black; the only way we could see anything, and they could see us, was through the glare of the submarine’s headlights. These animals had been evolving at these depths for millions of years; we’d been evolving on land for just as long. And here we were sharing space for the first time.

Beyond witnessing these life-forms, I wondered how else our presence might be interacting with theirs, what other information we might be broadcasting to one another.

As I sat there cramped in a tiny metal sub pondering all this, I felt an emptiness in my chest that breath couldn’t fill. The undersea is the largest living space on the planet, the 71 percent silent majority. And this is how it looks—gelatinous, cross-eyed, clumsy, glowing, flickering, cloaked in perpetual darkness, and compressed by more than 1,000 pounds per square inch.

I’d love to share with you some pictures or videos from my sub experience, but I didn’t take any. I was too busy being gobsmacked by wonders of the natural world and our place within it.

I guess you had to be there.

Source link