No products in the cart.

Outdoor Adventure

The Ultimate Guide to Olympic National Park

Ski in the morning, hike through an old-growth forest that same afternoon, then camp on the beach at night—welcome to Olympic National Park, one of few places on earth boasting such a wide range of ecosystems. Most park-goers find themselves asking not what to do here but how much they can cram into their visits.

The choices are copious and depend on your preferred setting and mode of exploration: you can wander the temperate rainforest or some 70 miles of coastline, paddle lakes and spend time at tidepools, backpack to more than 100 wilderness campsites, or head straight for the park’s rugged and remote crown jewel, 7,980-foot Mount Olympus. Don’t be fooled by its modest elevation; the peak is home to many large glaciers, including the three-mile-long Hoh Glacier, and requires an 18-mile approach, mountaineering skills, and a Class 4 scramble to summit.

Like many U.S. national parks, Olympic has a complicated history, but over the years, attempts have been made to right a few wrongs, some of which predate the park’s formal establishment in 1938. In the early 1900s, the Elwha and Glines Canyon Dams were built on the Elwha River to supply hydropower to the nearby town of Port Angeles. However, their construction flooded the traditional homelands of the Lower Elwha Klallam, violated the tribe’s treaty rights, and decimated salmon populations by blocking their migratory upstream route. In 1992, Congress passed the Elwha River Ecosystem and Fisheries Restoration Act, which, nearly two decades later, resulted in the largest dam-removal project in U.S. history. Tribal members and others showed up to celebrate in T-shirts emblazoned with “It’s about Dam time!” Today, the Elwha again runs free.

More recently, in 2018, in a quirky case, the National Park Service teamed up with the Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife and U.S. Forest Service to begin relocating mountain goats via helicopter from Olympic National Park to the North Cascades, over 100 miles away. Mountain goats aren’t native to Olympic and a dozen were introduced here by a sporting club in the 1920s. Over time the goats proliferated to a population of over 1,000, trampling rare and indigenous plants and disrupting natural ecological processes. The goat-relocation operation has attempted to restore the park to its original goat-free state while also supporting dwindling goat populations in their native North Cascades habitat. If you’ve ever wanted to watch a pair of goats fly off into the sunset, well, has the Olympic National Park YouTube channel got the video for you.

What You Need to Know Before Traveling to Olympic National Park

You can drive around the park but not through it

Unlike many national parks, Olympic contains no through roads. Ninety-five percent of the park is federally designated wilderness, in which motorized traffic is prohibited. The primary way to access different entrance points is via Highway 101, which roughly circumnavigates the park; however, those roads into the park essentially dead-end in 10 to 15 miles. Check road conditions in advance, keep your fuel tank topped off, and if you intend to visit the deep interior, plan to get there on your own two feet.

Plan to BYO bear can

Due to its abundant wildlife, Olympic has stringent food-storage regulations at its various wilderness campsites. Bear wires are available to hang food at many backcountry campsites, but for those without—including in the Enchanted Valley, High Divide Royal Basin, and the entire Wilderness Coast—you must have a Park Service–approved bear canister. (And no, Ursacks don’t make the cut. Olympic’s list of approved canisters can be found here.) You can borrow a bear canister for free from the Port Angeles, Quinault, or Hoodsport Wilderness Information Centers, but their supply can run out on busy weekends and, unfortunately, they can’t be reserved in advance, so bringing your own may be your best bet. Consult the Park Service’s Olympic Wilderness Trip Planner map to know what’s required where you want to camp.

For coastal hiking, carry a topo map and a tide chart

Several of the park’s coastal trails are only passable at low tide, so it is very important to time any beach hikes to avoid getting trapped or cliffed out when the water’s high. Tide charts can be downloaded from the National Park Service website or obtained in person at visitor centers or the Kalaloch ranger station. If you’re not sure how to use them in conjunction with a topographic map, ask a ranger for help in advance.

How to Get to Olympic National Park

There are multiple entrance points on all sides of the park, and most visitors tend to access them with a car. If you’re starting your drive in Seattle, count on a drive of at least two to three hours. And while you can motor around the south end of Puget Sound to reach the Olympic Peninsula, why sit in all that traffic when you could take a beautiful ferry ride across the sound instead? For destinations on the western side of the park, such as the Hoh Rain Forest and any of Olympic’s Pacific coastline, plan on a four-plus-hour trip from Seattle (whether you go by ferry or land).

Some parts of Olympic are also accessible by bus. The Dungeness Bus Line provides service from Seattle-Tacoma International Airport (Sea-Tac) to park entrance points like Port Angeles or Sequim, where you can then connect to the Clallam Transit System bus to reach other park destinations along Highway 101.

Port Angeles, home to the Olympic National Park Visitor Center—the only park visitor center that’s open year-round—is also accessible by ferry from Victoria, British Columbia.

The Best Time of Year to Visit Olympic National Park

As with many national parks, summer is its prime season, but Olympic’s biodiversity and ample lowlands make for plenty to see and do any time of the year.

Spring

Washington is called the Evergreen State for a reason—and Olympic National Park shines at its ever-greenest each spring, after the lush forests have spent the winter soaked with rain. (The Hoh Rain Forest, notably, receives about 12 feet of rain annually.) Plus, come spring, the park’s waterfalls are at peak runoff; check out the Olympic Peninsula Waterfall Trail for recommendations on some of the best routes and viewpoints. Many of the park’s trails are at lower elevation than other popular hiking meccas in Washington State, making them a great option for those seeking training hikes or backpacking trips in preparation for summer. Just be sure to pack your raincoat, every outing.

Summer

Summer offers myriad recreational opportunities at Olympic: hiking, climbing, cycling, camping, backpacking, paddling, and more. And while rain is at a minimum this season, crowds are at a maximum. Western Washington is a land of weekend warriors, so it never hurts to visit popular areas and campsites on weekdays when possible. During peak hours, plan on one-to-two-hour wait times to see sites such as Hurricane Ridge or the Hoh Rain Forest, as parking is limited and traffic is metered by the Park Service; smart travelers will plan to hit these areas first thing in the morning or late in the evening. (And thanks to the park’s northern latitude, daylight hours are long in the summer; close to the solstice, there’s light in the sky from 5 A.M. to nearly 10 P.M.)

Another option to avoid the masses is to hike into the park from trails in adjacent wilderness areas. You’ll still need a wilderness camping permit to spend the night within the park’s boundaries, but if you—like me—are bad at planning, you can pitch a tent sans permit in park-adjacent wildernesses such as at Marmot Pass (in the Buckhorn Wilderness) or Lower Lena Lake (in the Brothers Wilderness), then traipse your way into Olympic on foot for a day visit.

Fall

Yes, even rainforests have stunning autumn foliage: big-leaf maple, vine maple, red alder, and other deciduous trees provide an eye-popping contrast to the verdant mosses and ferns of Olympic. Plus, summer crowds have usually dissipated by late September, so it’s easier to find solitude. Fall also provides some unique wildlife-viewing opportunities: It’s mating season for the Roosevelt elk—the largest unmanaged herd of elk in the Pacific Northwest—so keep an ear out for their haunting bugles, which sound like a cross between a creaky metal gate and a trumpet. At the Salmon Cascades overlook on the Sol Duc River, you can see coho swimming upstream and leaping en route to spawn. Or watch sockeye spawn in the Quinault River come November and December; a good sighting spot is at Big Creek, about six miles northeast of Lake Quinault on North Shore Road.

Winter

Much of the park consists of lowlands that primarily receive rain, not snow, in the winter, making them possible to enjoy year-round. If it’s snow sports you’re after, though, Hurricane Ridge remains open on weekends all season long (as long as the road is open), with opportunities for cross-country, alpine, and backcountry skiing, snowboarding, tubing, snowshoeing, and more (see the Snow Sports section below).

Where to Stay in Olympic National Park

Outside Inc.’s National Park Trips offers a free Olympic Park Trip Planner filled with a complete itinerary, beautiful photography, a park map, and everything else you need to plan your dream vacation.

Lodging inside the park

Several options exist within park boundaries, each with its own charms and access points. Kalaloch Lodge is located on the Pacific coast, with a variety of accommodations ranging from rooms and suites (from $280) to oceanside cabins (from $300). In addition to a location near the park’s beaches, this lodge is also a good choice for those interested in visiting the Hoh Rain Forest.

Farther inland, on the south side of the park, is the beautiful Lake Quinault Lodge (from $304), built in 1926 on the shore of its eponymous lake. Open year-round, it’s an ideal base camp for lake adventures or exploring the Enchanted Valley, known as the Valley of 10,000 Waterfalls.

Two seasonal options exist on Lake Crescent, on the north side of the park, near Port Angeles: the turn-of-the-century Lake Crescent Lodge (open late April through November; from $164) and the rustic Log Cabin Resort (open late May to September; from $91), which will make you feel like a kid at scout camp all over again.

Slightly deeper into the park is the Sol Duc Hot Springs Resort (open late March through October; from $244), with quaint cabins and riverfront suites tucked into the woods. There’s no cell service or Wi-Fi at Sol Duc, so plan to enjoy an unplugged respite, complete with soaking opportunities in three mineral hot spring pools and one freshwater pool.

Nearby Lodging

With so many towns along Highway 101, there are countless choices near the park. Of them, the town of Forks is one of the most popular; not only was it made famous by Stephenie Meyer’s bestselling vampire-romance series, Twilight, it’s a quaint destination with quick access to beloved park beaches like Second, Third, and Rialto. Prefer to be right on the ocean? You can’t beat the Quileute Oceanside Resort (open year-round; cabins from $135). Located on the Quileute Indian Reservation in La Push, and owned and operated by the Quileute Tribe, it offers shorefront cabins, RV sites, and motel rooms within walking distance of the national park.

Camping

Camping is available year-round at Olympic. Many campgrounds are first come, first served, but summer reservations can be made at Recreation.gov for the Fairholme, Kalaloch, Mora, Hoh Rain Forest and Sol Duc campgrounds ($25-60/night), or by phone (888-896-3818) for the Log Cabin Resort RV and Campground ($40-50 for RV sites; $25-30 for tent camping). The park also boasts more than 100 designated wilderness campsites (including many on the beach); overnight permits are required but reservable online at Recreation.gov up to six months in advance. Dispersed camping outside of designated backcountry campsites is not allowed in Olympic National Park.

What to Do in Olympic National Park

Backpacking, Day Hiking, and Trail Running

You’ve heard of the PCT, but have you heard of the PNT? The Pacific Northwest Trail is a 1,200-mile corridor connecting Montana’s Glacier National Park to the Pacific coast. About 130 miles of the route passes through Olympic—including along its extensive Pacific coastline, from the Hoh Indian Reservation to Cape Alava, just south of the Ozette Indian Reservation. Hiking portions of the PNT is a wonderful way to escape the crowds and enjoy the remote interior of the park.

Consider checking out the 19-mile High Divide Loop through Seven Lakes Basin (typically snow-free by late July and through September) or the nine-mile Ozette Triangle (sometimes also called the Cape Alava Loop), which connects forested boardwalk trails with a three-mile stretch on the beach. Both make for awesome backpacking routes if you can get permits. If not, tackle them as glorious done-in-a-day adventures.

Want to get up close and personal with a glacier? Hike the 18-mile (one way!) Hoh River Trail to the foot of Blue Glacier on the flanks of Mount Olympus.

As far as day hikes go, a few favorites include those to Sol Duc Falls (1.6 miles round trip), Hole-in-the-Wall from Rialto Beach (3.4 miles round trip), Moose Lake (8.2 miles round trip), and Shi Shi Beach to Point of Arches (8 to 10 miles round trip; check your tide chart beforehand, and be aware that this hike also requires an additional $20 Makah Recreation Pass to access). For other great trails to hike or run, and a searchable database of trip reports, visit the Washington Trails Association website, which lets you refine your search results with all kinds of filters, including kid-friendly and wheelchair-friendly.

Surfing

This is adventure surfing. You reach Shi Shi Beach only by a two-mile hike through the rainforest, carrying your board and earning a one-of-a-kind backcountry surfing opportunity and an unforgettable view of a line of sea stacks. Make it a day trip, or get a camping permit here. You start at the Shi Shi Beach trailhead on the Makah Reservation. Be sure to purchase an additional recreation pass from the Makah Tribe.

The water is cold year-round, so bring a well-insulated wetsuit, and beware of the many riptides and rocks.

Lake Activities

Olympic is home to several large lowland lakes that are accessible year-round. From May to September, you can rent canoes, kayaks, paddleboats, or stand-up paddleboards at the Log Cabin Resort on Lake Crescent or at the beachside boat hut on Lake Quinault. In July and August, Lake Quinault Lodge—located on the lake on the Quinault Indian Reservation—offers boat tours at daybreak, afternoon, or sunset.

With few exceptions, most fishing in Olympic National Park is catch and release. The Park Service works closely with eight Native tribes to develop harvesting regulations to support indigenous fish while also providing recreational fishing opportunities for visitors. Learn more about the fishing regulations here.

Snow Sports

Come winter, all that rain down low is snowfall up high. With a summit elevation of 5,240 feet, Hurricane Ridge sees an average annual snowfall of more than 400 inches. It offers 20 miles of ungroomed routes and is a beautiful area for cross-country skiing and snowshoeing. Ranger-led snowshoe hikes are frequently available in the afternoons; inquire at the Hurricane Ridge Visitor Center.

Hurricane Ridge is also home to a small, family-oriented ski and snowboard area—one of only three such areas located within a national park. (Bonus: Indy Pass holders won’t have to buy a lift ticket.) Also known as Hurricane Ridge, it features two rope tows and a Poma lift, backcountry access and ski and snowboard lessons, as well as a tubing park. You can rent downhill skis or snowshoes at the visitor center. If it’s snowboard rental you’re after, or you just want to rent your skis in advance, swing by North by Northwest Surf Co. in Port Angeles before entering the park.

Parents of young kids can bring a sled or tube to the free Children’s Snowplay Area just west of the visitor center. (For older kids and kids at heart, the park encourages sliding at the formal tubing park instead.)

From December through March, the ski area is open weekends and Monday holidays, as long as Hurricane Ridge Road is open. Call 360-565-3131 or follow HRWinterAccess on Twitter to check the road status.

Cycling

Since all but five percent of the park is designated wilderness, there aren’t a ton of places within park borders to ride a bike. One exception is the four-mile, partially paved Spruce Railroad Trail, which runs along the north side of Lake Crescent. It offers a scenic respite from the Highway 101 traffic on the south side of the lake. Need to rent a bike? The Log Cabin Resort can hook you up.

Just north of the park, the 135-mile, Olympic Discovery Trail (ODT) runs from the Victorian seaport of Port Townsend all the way to La Push on the Pacific coast. More than half of the route is on a designated non-motorized path (with more segments being added each year), making it a fantastic way to tour the peninsula on two wheels. Additionally, paralleling the paved, rail-grade stretch of the ODT between the Elwha River and Lake Crescent is the 25-mile Olympic Adventure Trail, composed of singletrack and doubletrack open to mountain bikers, hikers, and equestrians.

All park roads are also open to cyclists. Gluttons for pain won’t want to miss the chance to ride up to Hurricane Ridge. If pedaling in traffic isn’t your thing, join Ride the Hurricane on the first Sunday of August each year, when the road closes to all motor vehicles, giving cyclists a opportunity to tackle the 40-mile ride from Port Angeles to Hurricane Ridge and back with ample space.

Stargazing

With a location far from major cities and the absence of many roads through the park’s interior, Olympic boasts incredible stargazing opportunities—as long as it’s not cloudy out (never a sure bet in the Pacific Northwest, but your best odds occur in summer). On a clear night, not only is the Milky Way spectacular, but the Andromeda Galaxy is also often visible with the naked eye. For a professional tour of the stars, check out the free telescope programs and full-moon hikes at Hurricane Ridge.

Wildlife and Tide-Pool Viewing

The park’s coastline is home to three national wildlife refuges: Copalis, Flattery Rocks and Quillayute Needles. All are closed to the public to help protect fragile wildlife populations. (Even if you come in by sea, regulations prohibit getting within 200 yards of them). So while it’s not possible to set foot on the refuges’ hundreds of offshore islands, reefs, and rocky outcroppings, many species can be viewed with binoculars from beaches such as Shi Shi, Cape Alava (on the Ozette Triangle), Rialto, Second, Ruby, and Kalaloch. Keep an eye out for everything from whales and puffins to elephant seals and sea otters. And spend time exploring the coast’s many vibrant tide pools.

Tree Hugging

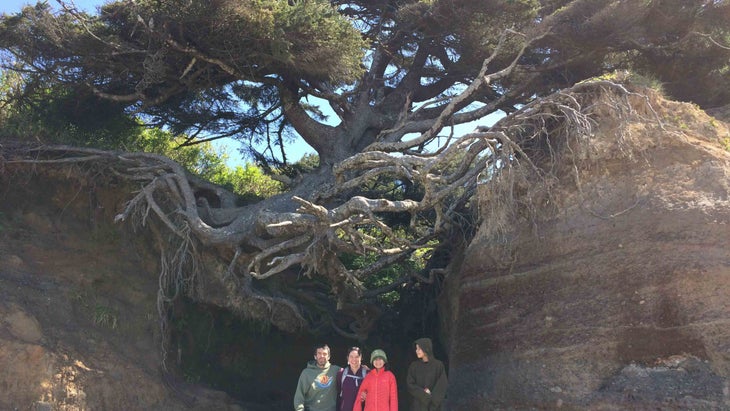

Some of the most famous trees in Olympic are found in the Hall of Mosses in the Hoh Rain Forest. But if you’re driving the whole peninsula loop, you might also want to ogle the world’s largest Sitka spruce, located on the (aptly named) Big Spruce Trail by Lake Quinault; the world’s largest red cedar, known as the Duncan Cedar, between Forks and Kalaloch; and, at Kalaloch Beach, the Tree of Life, a famous thousand-year-old Sitka spruce whose roots form a cave beneath it.

The Best Places to Eat and Drink Near Olympic National Park

As the largest city on the Olympic Peninsula, Port Angeles is your best bet for a wide variety of cuisine. But there are a few gems along the Highway 101 loop: Enjoy a cup of locally roasted coffee and a baked-from-scratch slice of carrot cake at the Rainshadow Café in Sequim. When you’re ready to refuel after a day of adventure, Granny’s Café, near Lake Crescent, or Clallam Bay’s Breakwater Restaurant, overlooking the Strait of Juan de Fuca, offer homey, diner-style cooking.

When you make it to Forks, stop by the Westend Taproom Tip and Sip to sample local craft beers and ciders and chat with residents. Farther south along the coast, the Creekside Restaurant at Kalaloch Lodge sources most of its food and beverages locally, with 100 percent of its wine offerings from Washington State. (The restaurant also serves a Tree of Life martini, using Washington-made vodka.) Top seafood picks include the Dungeness crab mac and Beecher’s cheese, classic ale-battered fish and chips, or a sourdough bread bowl full of clam chowder with bacon.

If you somehow make it all the way back around to the eastern side of the peninsula without sampling some proper Pacific Northwest seafood, stop at the Hama Hama Oyster Saloon, a one-of-a-kind outdoor eatery with rustic A-frame gazebos overlooking the water. Hours are limited and reservations are recommended. If you miss the saloon for whatever reason (shucks!), you can still shop at the neighboring Hama Hama Farm Store for everything from house-smoked oysters to fresh salmon to locally made ice cream.

If You Have Time for a Detour

Mountains, glaciers, ocean, rainforest… perhaps the only thing the Olympic Peninsula lacks is a big city. But from Port Angeles, it’s just a 90-minute ferry ride across the Strait of Juan de Fuca to reach downtown Victoria, British Columbia, which feels like a bustling metropolis after time spent on the peninsula. You can bring your car onto the ferry or just walk on and explore the Canadian province’s capital city on foot. (Don’t forget your passport, enhanced drivers’ license, or other travel documents.)

From the ferry landing, you can wander downtown, stroll the harbor, visit the Royal BC Museum, or walk out to the Breakwater Lighthouse (built in 1916) and admire the breakwater murals of First Nations artists along the way. Many visitors also venture out on the four-mile Dallas Road Waterfront Trail to have a gander at the world’s tallest freestanding totem pole— 127 feet high—at Beacon Hill, or stop at beaches along the trail such as Finlayson Point and Clover Point Park, where orca whales can be spotted offshore. And of course, pop in to a Canadian grocery store to procure some Coffee Crisp bars and All Dressed chips.

How to Be a Conscientious Visitor to Olympic National Park

Learn about the Native people who have lived on the Olympic Peninsula since time immemorial. Eight tribes—the Lower Elwha Klallam, Jamestown S’Klallam, Port Gamble S’Klallam, Skokomish, Quinault, Hoh, Quileute, and Makah—reside on reservations along the park’s fringes and maintain deep relationships with the land.

A great place to start your education is at the Makah Cultural and Research Center, which offers demonstrations and talks from tribal members on everything from Makah history to basketry to fisheries management. The center is also home to hundreds of artifacts from Ozette, a Makah village that was buried by a mudslide some 500 years ago and only rediscovered in 1970 after a storm exposed impeccably preserved artifacts.

Not all tribal lands are open to the public. When visiting park destinations on the coast, be attentive to signage and closures, respect people’s privacy, do not photograph individuals without permission, and leave all rocks, shells, driftwood, and natural artifacts here undisturbed. Learn more about visitor etiquette on the Quileute Nation website here.