No products in the cart.

Outdoor Adventure

This All-Girls Running Club in Kenya Protects Young Athletes

Agnes Tirop was a 25-year-old rising professional distance runner who represented Kenya at the 2020 Tokyo Olympics in the women’s 5,000-meters. One month after she competed in her first Olympic Games, Tirop set a world record for 10K. Just as her promising career began to bud on the world stage, her life came to an abrupt end on October 13, 2021.

Tirop was found stabbed to death by her husband Ibrahim Rotich at their home in Iten, in the Rift Valley of Kenya, a training hub for many of the world’s top professional distance runners. Rotich, then 41, attempted to flee the country, but he was arrested and charged with murder.

RELATED: Iten, Kenya, Is Where Running Champions Are Made

Tirop was a victim of gender-based violence (GBV), one of the most widespread human rights issues in the world. GBV, as defined by the United Nations, can include publicly or privately inflicted physical or sexual harm as well as economic suppression, threats of violence, manipulation, and coercion through various ways, including intimate partner violence and child marriage. According to the United Nations, while men and boys also suffer from GBV, women and girls are most at risk worldwide.

Nairobi’s Gender Based Violence Recovery Centre, founded in 2001, states that the country’s women and girls make up a disproportionately higher statistic. More than 40 percent of Kenyan women experience GBV in their lifetime, and one in three women in Kenya has experienced sexual violence before the age of 18. In the U.S., 20 people per minute are physically abused by an intimate partner, according to the National Coalition Against Domestic Violence, and more than 10 million adults experience domestic violence each year. National statistics about domestic violence show that one in three women have experienced some form of physical violence by an intimate partner.

Female runners are among those numbers. Many Kenyan professional runners can fall into marriages or partnerships that take away their autonomy. Some of these women—powerful, driven, and successful in their careers—remain under the watch and control of their partners. Most women in GBV situations don’t know how to escape, or fear the repercussions of doing so.

Tirop’s tragic death made international headlines and served as a wake-up call about the dangers elite female athletes can face during their careers.

The Courage to Stand Up

In the aftermath of Tirop’s death, 34-year-old Kenyan professional marathoner Mary Ngugi took a stance.

“With my platform as an athlete, I have a voice that I can use to change,” says Ngugi, who has raced professionally for more than a decade and twice finished on the podium at the Boston Marathon. “I can’t change the whole of Kenya in one minute, but I can make a change in athletics with girls.”

RELATED: Mary Wacera Ngugi is Speaking Out About Domestic Violence

Ngugi established Nala Track Club in Nyahururu Town, Kenya, in October 2022. Through the club, located 100 miles north of the country’s capital Nairobi, Ngugi aims to shelter and support young girls as they simultaneously pursue their education and ambitions of becoming elite champion runners.

“The best thing is to mentor them when they’re young, to empower them so they know that they deserve better, [and] to know that they have a choice,” Ngugi says.

Ngugi, who is based in Leeds, England, with her husband, British sports photographer Chris Cooper, says that traveling the world to compete over the years exposed her to fairer treatment of women and girls compared to what she witnessed and experienced firsthand while living in Kenya.

“There are some things that have always frustrated me,” Ngugi says. “When I was 17, there were young girls in [training] camps who were abused by their coaches. Some [girls] are married at a tender age because of money.”

Ngugi says it’s not uncommon for young female runners to be afraid of their male coaches. Her idea for a girls-only running camp has been years in the making, initially as a way to give back to the community. Not until after the death of Tirop, whom she knew as an acquaintance, did Ngugi move her mission forward.

“It took a lot of courage to start,” she says.

Ngugi funded the camp entirely when it opened, covering the costs of housing, school fees, food, training gear, and other basic supplies for eight girls. Unlike most traditional training camps for runners in Kenya, which typically consist of small single-room apartments, the girls at Nala Track Club live together in a home under the supervision of a matron, who cares for and cooks for them. Ngugi stipulates that each member of the club must attend school if they want to remain a part of Nala.

“We don’t want to be just another running camp. We have loads of those in Kenya. Education makes a difference,” Ngugi says. “As much as I want all of my girls to make it, I know some won’t. That’s the reality of things. But I would like for them to come out of the camp with an education so that they can do something with their lives, pursue a cause or a degree.”

Should any of the girls become successful in their athletic careers, Ngugi’s mission is also to ensure they are equipped to make informed decisions, especially financially, that are in their best interests.

“These athletes could potentially earn millions of shillings,” Ngugi says. “How are you going to invest? How are you going to sign a contract? How are you going to carry yourself with the press when you get an interview? We want them to be able to handle themselves.”

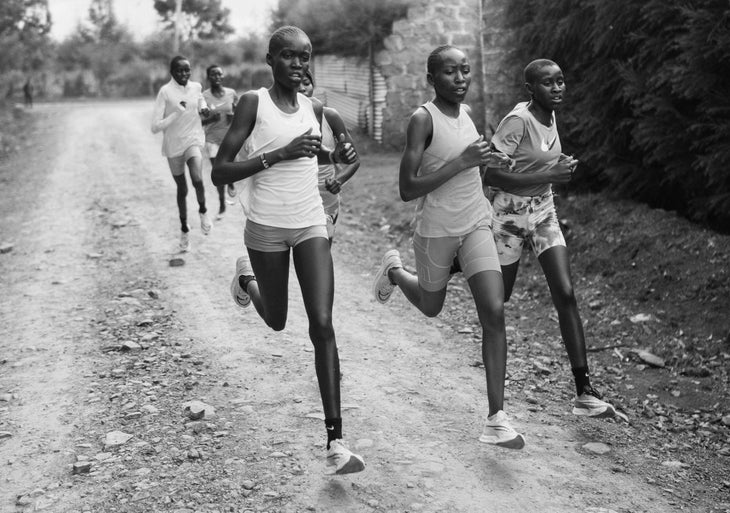

Women Coaching Women

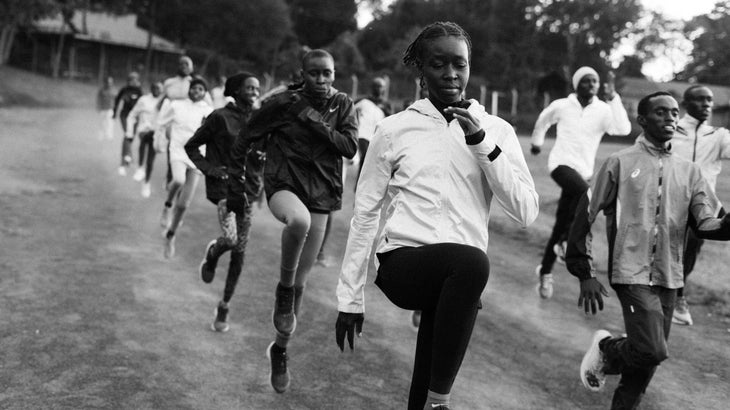

In a year since founding Nala Track Club, Kenya’s first all-girls running camp, its members have doubled to 16 girls and women between the ages of 14 and 22. Ngugi says the camp is now fully supported by Nike, her sponsor since 2006. She works closely with teachers and schools throughout Kenya to recruit national-caliber talent and prospects.

Ngugi splits her time training in the UK and Kenya. When she’s not on the ground in her home country, she helps oversee Nala from afar under the guidance of a few certified running coaches that help craft the training program, which is shared with Lilian Mugo, a local woman whom Ngugi is helping to mentor into a running coach.

Ngugi wants to develop female coaches in Kenya. To her knowledge, few, if any, women are currently coaching female runners in Kenya. “That’s one big reason why we started Nala,” Ngugi says.

Ngugi has never been coached by a woman at any point in her career. It’s a role she envisions transitioning into full time in the future, after she retires from competitive running. After a successful track career that included becoming a two-time world half marathon medalist, Ngugi transitioned to road marathons in 2019. She was runner-up at the 2021 Boston Marathon and finished third in 2022. Ngugi placed fifth at this year’s New York City Marathon.

Achieving that level of success as an elite athlete is a dream, though not the lone goal, for the girls of the camp. At the very least, Ngugi wants to develop members of the track club to compete on the international level feeling empowered. The name of the camp, Nala, is a Swahili word in reference to lioness and also connotes the idea of a successful African woman.

“I want them to be more than just athletes. I want the girls to know their worth and to be role models to others,” Ngugi says. “I always tell my girls, ‘remember what Nala stands for: Powerful. Confidence.’ That is what we want our girls to be.”