No products in the cart.

Outdoor Adventure

Finally, an Artificial Campfire That Doesn’t Suck

There’s nothing better than cozying up around a campfire before you crawl into your tent for the night. But campfires are increasingly banned following a historic fire season in New Mexico, more and more acres burning in California, and worsening drought in the West. That’s the problem Howl Campfires is trying to solve in developing its new propane-powered campfire. Its innovation? It’s genuinely warm.

The idea was born on a photoshoot for GoFastCampers, outside Bryce, Utah, two years ago. Randall Slimp brought along his Toyota Tundra, and, realizing campfires were banned in the drought-stricken Dixie National Forest at the time, decided to pick up a propane fire pit at a big box store along the way.

While wood campfires are commonly banned on public lands when wildfire risk is high, portable stoves, fire pits, and heaters typically remain permitted (although you should always double-check before you go).

But setting up the fire pit in camp the first night, Slimp realized that while its flames provided some nice atmosphere, they did very little to keep the group warm.

“It was so cold that night, that I had to put on my down pants,” says Kelly Lund, owner of the Insta-famous dog @Loki, who was also on the trip.

Another problem occurred the next day during the shoot: Slimp loaded the large metal bowl and a 20-pound propane tank into the back of his pickup, but struggled to find a way secure either of them due to their awkward shapes. Bouncing around off-road upended the fire pit, spilling its decorative lava rocks all over the bed. And when the propane tank started to roll around, it ground the rocks into an abrasive powder, which got into all of Slimp’s camping gear. Frustrated, he and Lund started to spitball solutions.

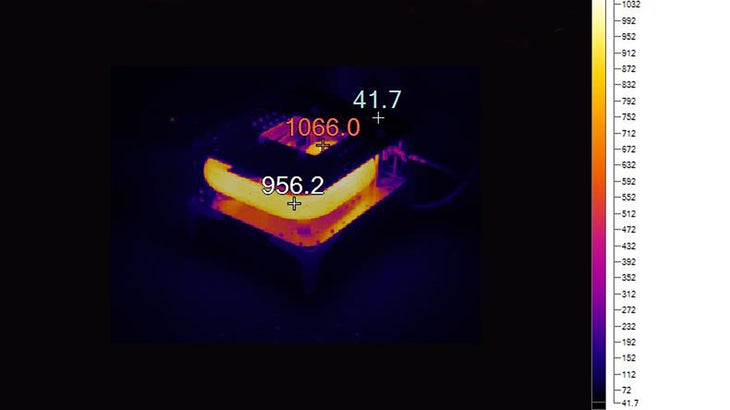

When they returned home to Colorado, the pair began researching what makes wood campfires so nice to be around. It turns out there are three kinds of heat: conduction transfers heat through touch, convection transfers heat through the air, and radiation transfers heat through infrared waves. While propane fire pits are hot to the touch and heat the air directly above the flames, they don’t provide much radiant heat. And that’s why standing around one doesn’t warm you up.

“Wood coals put out infrared rays at the ideal frequency for warming water,” says Lund. “Our bodies are mostly water, so those rays excite the molecules in our cells and generate heat.”

To mimic the radiant warmth of a real campfire, Slimp and Lund needed to find a way to heat something so it’d glow bright orange, just like wood coals. And they wanted to use propane, since the fuel provides much more energy density than batteries, is easily transported, and is universally available.

The first prototype was basically a miniaturized tube heater hooked up to a propane tank. It squirted propane down a tube, then employed a fan to blow air through the tube. Once lit, the tube glowed nice and hot, but the fan was loud and required an electric power source. In fact, the tube got so hot that it ended up melting the wires in the fan. and the team realized that creating an ideal air-fuel ratio would require tweaking at altitude, where there’s less oxygen.

“We wanted to create something durable that didn’t require a battery,” says Slimp. And the solution was a Venturi.

By releasing pressurized propane from a tank and flowing it alongside air through a constriction into a large chamber, the current of the propane itself drew with it large quantities of air. This eliminated the need for a fan and its associated electronics, and the volume of air pulled into the combustion chamber was large enough for it to work at altitude. Slimp says his team has successfully tested their prototype at 9,000 feet and plans to take a production unit up Pike’s Peak (14,115 feet), once they’re ready later this year. Howl’s performance is already impressive. Typical portable propane heaters, like the Mr. Heater Buddy, stop working at about 7,000 feet.

“In our system, the high-velocity propane jet produces a constant momentum, which then moves a constant quantity of air molecules with it,” says Alex Tenenbaum, Howl’s engineer. “There should be no difference in heat output or burn velocity, whether you’re at sea level or in the Himalaya.”

The other problem the team ran into was achieving complete combustion of all that propane being squirted into the tube. Resolving that was simply a matter of a quick phone call with prolific outdoor product designer Owen Mesdag.

“If you aren’t burning all the fuel, you’re producing carbon monoxide,” says Mesdag. “So I told them they needed to give the fuel a target.”

By squirting the fuel-air mixture from the Venturi into metal mesh, Mesdag says that they “give the flame a home,” where complete combustion is able to take place. The flame exists within the mesh at the start of the tube, and the Venturi’s pressure then blows through the tube’s contortions.

For the visual effect of a campfire flame, propane is also released from a burner in the Howl Campfire’s center, with its flames protruding from the device’s top.

The final challenge was portability. Howl enlisted the help of Eric Black, a product designer based in Porland, Oregon. Black proposed using the campfire body as a stand for the propane tank. By unifying the cylinder and body, the solution turns an awkward combination of a round tank and a box on legs into a single stable cube about the size of two bundles of firewood, complete with tie-down points. To secure it in a vehicle, all you need is a tie-down strap. The team tells me a single 20-pound tank should be enough to run the fire on full blast for about 7.5 hours, which should give users two full evenings of use on a single tank.

Howl plans to produce its Campfires from “mostly American” components, at a facility outside Houston, Texas. They’re hoping sales will start in time for Christmas, 2022, and are targeting a price point somewhere north of $800.

Worth it? As wildfire season in the West grows close to year-round, and irresponsible camper behavior continues to force land management agencies to ban wood fires in more and more places, solutions like this one are increasingly going to become the only viable option if you still want to have a campfire when you go camping.

“Our goal is to keep the campfire alive,” says Lund.