No products in the cart.

Outdoor Adventure

Into the Mystical and Inexplicable World of Dowsing

Even today, finding water underground can be a gamble. You may search the landscape for clues, for a valley, say, or a cottonwood stand. You may unfurl a geologic map, scanning for underground pockets where water pools. You may study your neighbors’ wells to surmise the depth of the one you will drill. Or you may hire a geologist to do all that for you. But none of it guarantees that a rig won’t just turn dirt, and missing is expensive. In New England, for instance, every foot bored can cost $15, and the average well depth is 280-odd feet. Ultimately, there’s no way to know for sure what’s underground until you dig. Most guess and hope for the best.

But some look elsewhere. Dowsing is the old-world way of finding things. It is not, definitively, a science; it is pre-science—a method born before the Enlightenment to find, among other things, water, minerals, oil, gemstones, buried treasure, energies emanating from the earth, fugitives, missing kids, missing dogs, missing cats, and, according to some fervent practitioners, the pears that are ripest in the produce aisle. Its names are as numerous as its aims: divining, doodlebugging, water witching, water smelling, peach-twig toting, well prophesying, rhabdomancy, and, from the lips of the most pragmatic among them, finding water with a stick. Dowsers locate their targets based on the movements of handheld rods, which can be anything from branches to bastard files to horsewhips. They also use pendulums: a penny on a wire, or keys suspended from a Bible, or quicksilver in a bottle on a string. The power is not in the device, for it merely channels, dowsers say; the power is out there, and an attuned hand and quieted mind can discern it.

Detractors say it’s all hooey. Science has shown that hidden desires can move your muscles subconsciously, and this is why the rods point and the pendulums swing. (This “ideomotor effect” also explains Ouija boards.) Successes are exceptions. Dowsers are charlatans who more often fail to find what they seek, or find it by dumb luck.

Many of those who hire a dowser say they don’t know how the magic works, only that it does. “It’s just—insane,” says Steven Strong, a homeowner in Vermont’s Upper Valley. “I’m an engineer. I know physics. I can’t explain any of it.” But when the well on his property stopped producing about five years ago, the man Strong contracted to drill a new one had no idea where to put it. (Drillers don’t locate the water; they only strike it.) At the driller’s recommendation, Strong hired a dowser, a man from up north named Steve Herbert.

He watched Herbert circle his property for some time. Then, about 50 feet from the dried-up well, the dowser hammered a stake into the earth. He proclaimed that, if placed right here, perfectly vertically, the rig would hit a spring that gushed 25 gallons per minute of good, clean water. The driller drilled. Water rushed. “Honest to goodness, without any embellishment,” Strong said, “it was exactly spot-on. Not 23.5. Not 26. But 25 gallons a minute. I was there and I didn’t believe it, and the well driller was slack-jawed.”

“I’ll tell ya,” that driller, George Spear, said, “whatever it is, if someone ever unlocks the mystery, it’ll be amazing, because some people have it.”

Drilling companies rarely recommend dowsers to their clients, but the practice is common nonetheless. Associations have formed around the world to study dowsing and teach its power. There are, among many others, the British Society of Dowsers, the Irish Society of Diviners, the Dowsers Society of New South Wales, the Canadian Society of Dowsers, the Japanese Society of Dowsing, the Asociación Argentina de Radiestesia, and the Ceska Psychoenergeticka Spolecnost, in the Czech Republic.

The American Society of Dowsers, headquartered in Danville, Vermont, has some 2,000 members. They hail from every state in the union. Most live west of the Mississippi. Very few—not even 50 in the U.S., a veteran dowser told me—have been at it for decades like Leroy Bull has. Most are hobbyists, Bull says.

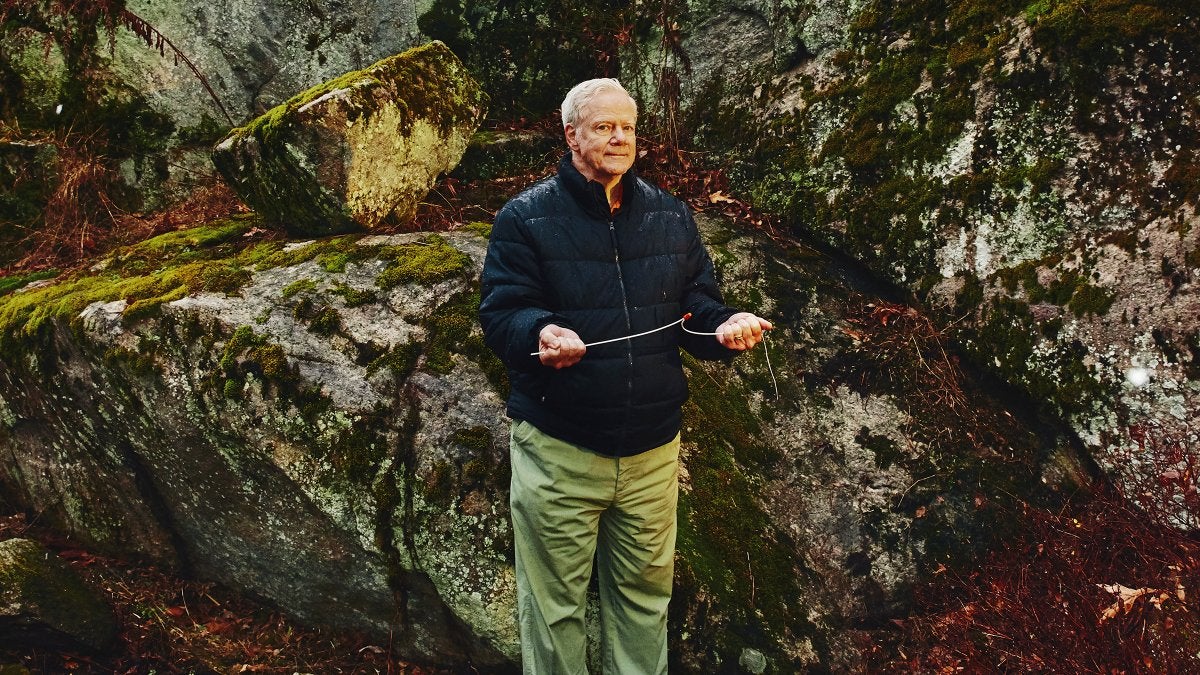

Bull was once the president of the American Society of Dowsers and is considered a sage in his field. One source I spoke to called Bull the best dowser in America. Bull says he has found more than 1,500 well sites in three countries. He may have a knack for water, but he’s received calls from seekers of many other things. Car keys. Cash. Wills. A long-lost galleon. Also: missing people, which can be dark work. About a week after 9/11, he says, an FBI agent called to ask whether anyone was still alive in the fallen towers. They’re all dead, Bull reported. Last September, he says, he was called to help find a paraglider who had disappeared somewhere in the Nevada desert. Later that month, a driver found the paraglider; he was dead. Neither the FBI nor the Nevada Division of Emergency Management would confirm Bull’s involvement in these investigations, but the federal government has, on occasion, consulted clairvoyants, according to case files. Even today, so late in his career, Bull receives about three requests each month. He charges $300 to $400 a day, plus expenses.

Source link