No products in the cart.

Outdoor Adventure

Lessons Learned from a Setback at the Crag

This feature by award-winning author Jeff Jackson first appeared in Rock and Ice, July 2020.

I one-fell my Ultimate Project on a Saturday. A few days later, Michael Victorino, the mayor of Maui, issued the stay-at-home order about to take effect. I had cruised the first nine bolts and gotten to the rest fresh enough to trade out in the horizontal and think, This could be it. I might finally send.

I released the foot jam and swung like a tamarin, stabbed my toe at the shoulder-level horn out right and stuck it, locked down and grabbed a little sloping edge no bigger than a pencil and greasy as a Schüblig sausage. Boned up, flagged hard and started to cross when my fingers snapped off the edge and I plunged through the gulf, arms whirling, machine-gunning expletives, ungainly as a dodo bird.

After boinking, I pulled on without resting and sent the route to the top. Uncle Chris Janiszewski lowered me, and we bumped fists (remember bumping fists?).

“Next go,” he said.

And then: Pandemonium.

***

I’ve had projects pretty much nonstop for 40 years. I’ve gone on road trips and picked a line and given it all my gorm for days. I’ve worked projects at local crags weekend after weekend. I’ve had projects in hard-to-reach places, and spent years striving and training and visualizing, whispering positive aspirations and ruining relationships, gearing up, hiking in and trying hard, and then after almost losing my grip on reality, I’ve sent my lifetime projects and experienced that feeling of ecstatic release like the guy with a pimple on his leg who squeezed out a Tumbu fly maggot the size of his thumb. And then, 20 years later, I’ve watched Alex Honnold walk out with a friend one morning and onsight my nine-pitch megaproject.

The project before my Ultimate Proj—let’s call this one my Penultimate Project—was supposed to be my last project, but I never sent it. Didn’t spend weeks refining my beta or tweaking my diet. Didn’t feel the urge to cry or call my parents. Didn’t progress the sport or even improve myself, not even a little bit. I just gave up. Threw in the towel. Quit.

I’d projected the Penultimate Project, a steep, slopey line at Plenty Kiawe for a couple of weeks and watched GuiJ Marun—big-wave surfer and one of the most prolific new routers in Maui—do it, and then a visiting Austrian named Stefan fired it, and then Babsi, his girlfriend, did a lap.

After I left it for the summer and got back on it this fall, the Penultimate Project felt painful and committing and scary, just the way I remembered.

“I’m done with this piece of shit!” I shouted down to Coco Dave after hanging at every bolt.

We both knew what I meant. It was too hard. I’d have to suffer hard and fail over and over, and let it get into my head. And then it would mess with my mind. And I’d start to care. And then I’d fall in love with it. I’d go to sleep thinking about it and wake up thinking about it and daydream about it. I’d fantasize about putting my hands on it and when it finally came time to get my hands on it, it would reject me. And I’d fret and worry and go back to it again and again, for months or years. We’d develop a dysfunctional relationship, a one-sided thing where I took care of it—groomed it, blew on it, looked lovingly at its shapes, hung colorful baubles on it—and it would remain obdurate.

Then one day I’d do it. Maybe it would feel easy. The relief would be immense, like barfing up a hot iron ball or having a 10-minute orgasm. I’d feel free for a moment. But then I’d fall in love again.

Coco Dave shouted up some encouragement. “You got it, dude,” he said. “We’ll do some hangboarding.”

Training? That seemed a little extreme.

I hesitated. Didn’t I want to climb hard anymore? What was happening to me? Was I finally getting too old for this sport? Somehow, I couldn’t muster the energy to care. I pulled the draws on the way down and basked in the happiness of giving up. Maybe I was done projecting forever.

***

Consider what the Buddhist master and philandering alcoholic Chogyam Trungpa had to say about the human condition: “Really, we operate on a very small basis. We think we are great, broadly significant, and that we cover a whole large area. We see ourselves as having a history and a future, and here we are in our big-deal present. But if we look at ourselves clearly in this very moment, we see we are just grains of sand—just little people … ”

In other words, you are just a speck of insignificant, unimportant, inconsequential and trivial nothingness stuck to the shoe of the universe. Littler than the swage sleeve on a #1 micro Stopper. Smaller than Ramon Julian Puigblanque’s pinky toe. On a cosmic scale, even Adam Ondra is nothing special, which makes you and me … well, let’s not get too incisive here. Suffice it to say that we’re completely irrelevant. And so are our projects.

***

I suppose it’s time to talk about Adam Ondra and the Hard, Hard, Hard.

For a long time, all we knew was that Project Hard, Adam Ondra’s Norwegian super proj, was the next level up. Harder than The Hard Hard (La Dura Dura), the nails-hard previous world’s hardest climb. Four years went by, and Ondra still hadn’t done Project Hard, but he continued to rage—accomplishing hard things like onsighting 9a, winning World Championships, bouldering V16s, crimping tiny granite chips across the Dawn Wall, finishing university and learning languages and being this nearly-too-good-to-be-true, smart, funny, humble-but-real, all-around best rock climber in the world.

And then, finally, he did it. The Hard Hard Hard. La Dura Dura Dura. Ondra later changed the name of Project Hard to Silence, because, as he put it: “I could not even scream. All I could do was just hang on the rope, feeling tears in my eyes. It was too much joy, relief and excitement all mixed together.”

What does it take to send the world’s hardest project? Find your way to the humungous Hanshelleren Cave in Norway. Use Sherlock Holmesian deduction to locate the start of Nordic Flower (5.14b) among a bewildering grouping of quickdraws dangling like villi in the duodenum of Scandinavian jotun. Climb halfway up that line, link into another one and finish via a V15 crack, into a V13 to another number I can’t climb, blah, blah. (Honestly, the blow-by-blow is less interesting than my neighbor Larry, 91, standing in his garage talking about his tools while his Datsun’s motor is running.)

Things to remember: Ondra hung upside-down for long intervals to train his circulatory system so he could milk an inverted kneebar and not have to worry about the blood filling his head until his eyeballs exploded. He also let a man named Klaus hold him in compromising positions for long periods of time. He also asked a ballet instructor to watch a monkey and report his findings. These are techniques you and I would not avail ourselves of.

Also, Ondra climbs full-time, has a coach, a PT, a PR agent and a videographer, rocks a wispy Czech afro, and has a neck like a Tula fighting goose. He speaks Czech, English, Spanish, Italian, French and Cherokee. This guy might be the first World President. He also might be an elf or a wizard.

***

Ondra once told my buddy Andrew Bisharat that projecting was his least-favorite kind of climbing. He said that he could easily just climb 5.15b and keep his sponsors happy and not have to try so damn hard on the Hard, Hard, Hard.

But he also told AB that he just has to try as hard as he can. Like John Lee Hooker and the boogie woogie, it’s in him and it’s got to get out. And just like John Lee’s papa, I say, “Let that boy boogie woogie.”

But there’s something equally liberating about not working so damn hard.

We’ve been told our entire life that quitting is bad, that quitters never win and that quitters develop the habit of quitting. If you give up a few times, pretty soon you’ll become one of those people who say things like, “This is my summit.”

Look at any study on satisfaction and you’ll see that happiness is concomitant with completing tasks that have an appropriate level of difficulty. The psychologist Mihály Csíkszentmihályi, who coined the term “flow,” pointed out that this energized and intrinsically rewarding state only arises when the task at hand requires intense focus. Too easy and you get bored. Too hard, you get bored. Turns out life is just very boring and the only way to stay stoked is by projecting 5.15 or doing brain surgery.

I googled “satisfaction” and a 2017 study popped up first. A Harvard Business School professor, Teresa Amabile, and psychologist Steven Kramer found that 1,200 workers reported their happiest days as those marked by a sense of progress.

“Ultimately, work is really about accomplishment,” the researchers noted. “Did I get something done, and does it matter?”

The question, of course, is whether you want climbing to be like a job. We do call it “working a route,” after all.

After indulging in a similar train of thought for a couple of days, I decided that I was officially done with projecting forever, and the next weekend, instead of warming up on The Vegetarian Paniolo and Jahawaiian, and trying hard on the Penultimate Proj, I found myself hiking with Arnie Dungo, a loquacious and hardworking Maui carpenter about my age, into a canyon with sweeping 100-foot walls and seven new 5.10s.

We got to the base of a steep red-and-gold wall liberally etched with tacky edges and pockets. Arnie belayed me on an amazing 14-bolt route, Amazeballs (5.10c). I didn’t try hard and I totally sent that shit. We did all seven lines, 700 feet of 5.10, and I couldn’t believe how much fun rock climbing was.

The next weekend we were back. We did the seven 5.10s and it was totally amazeballs.

By the next weekend, however, Amazeballs wasn’t quite as amazing and I was starting to feel a familiar pull. I kept stealing glances up the canyon toward The Syllable, a 90-degree slab with holds the size, shape and texture of crumbs at the bottom of a popcorn bag — an old project that had taken weeks to send.

By the end of the day, I knew that my self-imposed lockdown was over. It was time to get back to work.

***

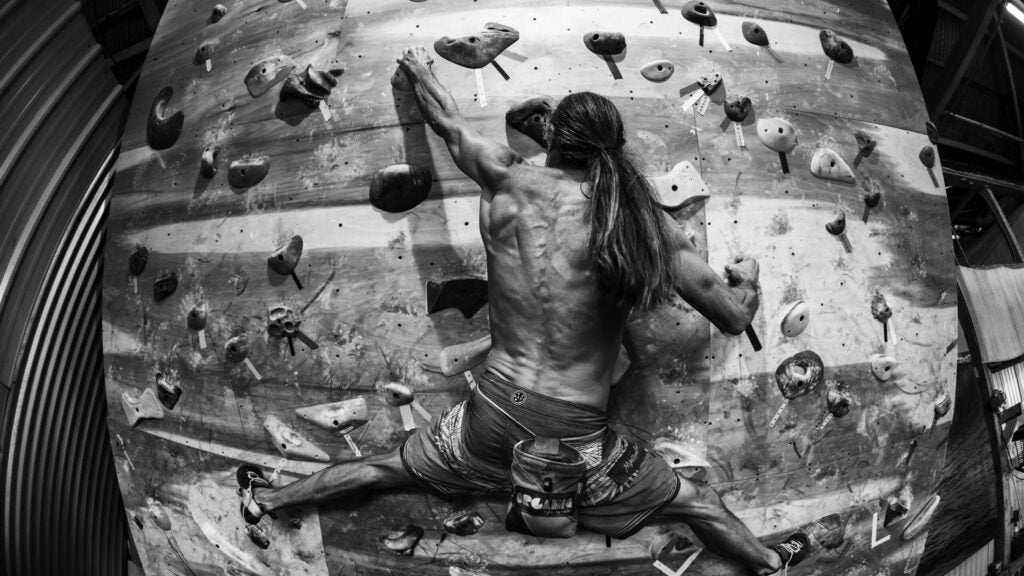

And so the real work began. Needing yet another new project, I picked out an appropriately impossible-looking line and spent a few days gluing 15 titanium bolts into its belly. Then I brushed every hold I could reach with an electric, rotary wire brush, a full-sized wire brush, a smaller wire brush, and a toothbrush. Then I took a nut tool and scraped any gunk out of the pockets. I pried off loose flakes and glued the loose flakes I couldn’t pry off. Used a one-inch blow tube to blow dust out of pockets and cracks. Went back over it with a ½-inch blow tube and then borrowed GuiJ’s electric leaf blower and blasted it until it was cleaner than a vegan’s colon. Then I felt the holds and chalked ’em up. Brushed it some more. Moved a bolt or two. Pried off another hold. Added some glue. Brushed it again and blew off the holds. After only five days of prep, it was ready to try.

I gave it one burn and realized it was way too hard for me. So, I started training and I trained too hard and hurt my shoulder. After rehabbing my shoulder, I got on the Ultimate Project and tried too hard and tweaked my knee. I had to project another project that wasn’t the Ultimate Project for a few weeks while my knee healed. Miraculously, I sent the project to the left of the Ultimate Project.

The work was paying off, so I kept training and doing my rehab, and every night before bed I’d sit cross-legged and visualize the Ultimate Project while sipping magnesium tea to ease my old, aching over-trained muscles. And every Sunday I’d crawl a little farther out my own Project Hard, until one day I arrived at the rest below the crux and thought that maybe, just maybe, I would send.

***

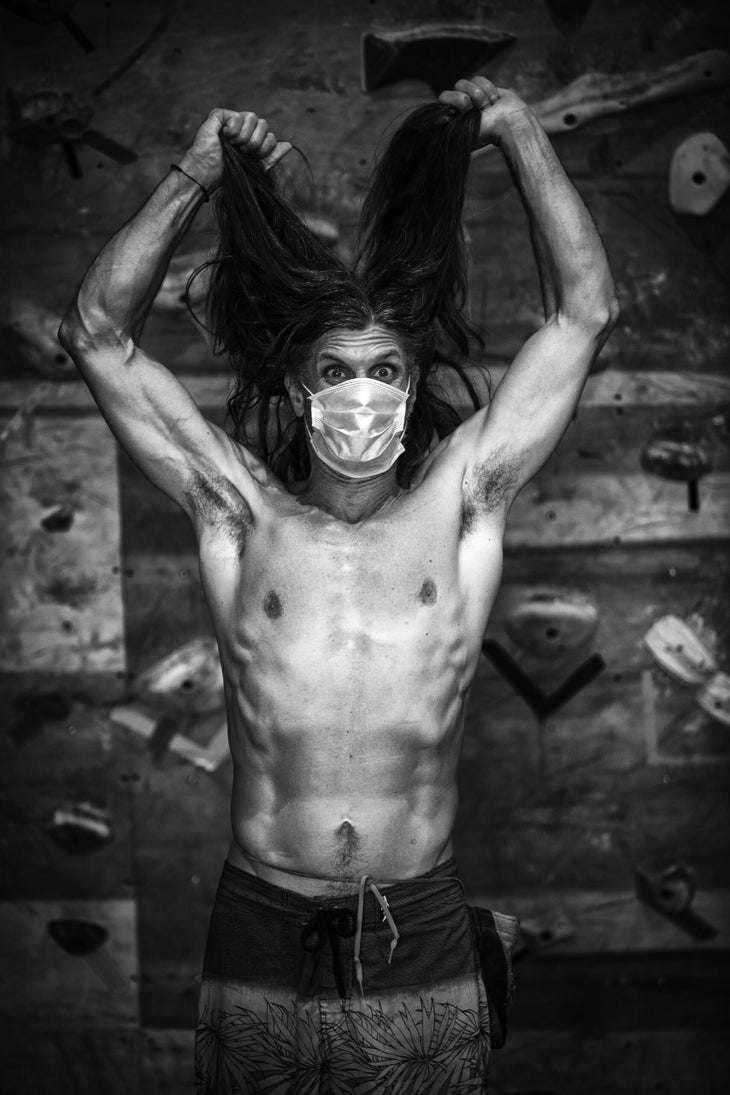

On March 25, Mayor Victorino ordered that nobody is supposed to leave home. The majority of the Maui community works in the tourism industry and most people lost their jobs. Cops are handing out $5,000 fines, and the National Guard has set up a roadblock on the Pi’ilani Highway and cut me off from the Ultimate Project.

As I write this, exactly 30 days after the mayor’s stay-home rule, it looks like it might be another month before they let us out. I haven’t been climbing in weeks and I know now what Ondra meant when he said he just has to try hard. In fact, after 30 days of not working, I would like nothing more than to try hard on the Hard, Hard.

I like to think of it—shady and cool, my draws swaying in the gusty northeast breeze. It’s not waiting for me. No, the Ultimate Project just is. It’s out there, it exists. One day I’ll get to try it again, and for now, that’s enough.

Jeff Jackson is the At-Large Editor for Climbing.

Source link