No products in the cart.

Outdoor Adventure

My iPhone’s SOS App Saved My Thru-Hike

Outside’s Trail Magic hiking columnist Grayson Haver Currin recently completed the triple crown of hiking when he finished the Continental Divide Trail alongside his wife, Tina.

After three months of hiking on the Continental Divide Trail, my trip became thrown into chaos this past October in just three hours. The ordeal reduced my focus to a single and vexing question: where the hell was my wife, Tina?

Over the ensuing 34 hours, that single worry ballooned into a dozen related terrors: Was she hurt or dead? Did she think I was hurt or dead? And was I at risk of actually dying alone, high in Colorado’s San Juan Mountains, where the first gusts of winter had just ripped against the peaks? These worries spiraled back into one urgent question: Exactly how was I going to find Tina?

Let’s back up: two days prior, Tina and I had waited out a ferocious storm in an old mining town near Lake City, Colorado. Almost every hiker we knew had stopped, pausing our quests for the Mexican border in favor of Falstaff’s dictum about caution over valor. Climbing south out of Spring Creek Pass the next morning, though, the snow was deeper than anyone had anticipated, shin-high and tightly packed. In one section the route was steep and slick, and a dozen thru-hikers—our arms atrophied into string beans after three months of little use—pulled ourselves up on all fours, using whatever pathetic grip strength we might muster.

We made camp that night in a foot of snow near a trickling creek, every hiker huddled together like pioneers crossing plains. The next morning was cold, with frozen gear and shivering arms keeping us in our tents until late in the morning. We’d aim for only 21 total miles that day, we said, with a possible goal of climbing another mountain along the way.

After breakfast, I kissed Tina goodbye, our tent stuffed in my pack and our stakes stuffed in hers, same as always. I plowed ahead to get warm, the two of us slowly spreading apart on trail as we’ve done for four years and 10,000 miles of trekking. I climbed a pass, crossed a ridge, and, after an hour, descended to a little alpine lake with enough broken ice for me to filch the day’s first drinking water. I sat there for half an hour, waiting for Tina to catch up. She never did.

For the next day and a half I searched for Tina on one of the most infamous stretches of the CDT without cell-phone service. Finally, I decided to see if my Apple iPhone 14’s emergency response app actually performed the way it was advertised. I linked to a satellite, sent an SOS message, and asked a stranger somewhere in space to answer my vexing question: where was my wife?

The technology worked—for the most part.

The Challenges of the CDT

On most long trails—think the Appalachian, Pacific Crest, and Arizona trails, among others—hikers follow a standard route, periodically marked by signs or swatches of paint that verify the way.

The CDT, however, is different. It is not, in fact, a trail at all so much as a series of interconnected routes and roads, allowing you to map your own path between Canada and Mexico within certain loose parameters. Almost 50 years after the CDT’s inception, the route does boast a standard trek, but sticking to this agreed-upon route isn’t standard. Feel like tacking on a peak today or staying low and out of gnarly weather tomorrow? It’s all acceptable on the CDT.

On the morning of our separation, as I trudged through the snow, I intersected three hikers we’d climbed alongside the day before, now headed northbound. They had been slogging through the snow for three hours already and had only covered three miles; they were doubling back to the Pole Creek Trail, which would drop them into a sunny valley mostly devoid of snow, where they might speed ahead. I wished them well and then pressed on southward, to the lake where I waited.

When 30 minutes had passed with no sign of Tina, I knew something was wrong. We’ve now crossed the United States together multiple times; our paces are so consistent that I expect to gain three minutes on her per mile, almost without fail. We were at twice that gap now, emergency mode. I dropped my pack next to a wooden post and reversed course, calling her name and standing on every available high point to see if she’d somehow slipped from the snow.

I kept at this for nearly two hours before finally studying the footprints at the trail junction. I’d only seen three hikers opt for the lower route, but I spied at least four distinct sets of prints—including the knobby lugs of Hoka Speedgoats, a little smaller than my own feet. They must be Tina’s, I thought. I raced the mile back to my pack and cut across a steep slope thick with willows, aiming for the low route. I knew I could catch Tina in that snowless valley that afternoon if I pushed my pace, despite losing two hours in my search with no rescue.

Yes, I wanted to climb the snowy peaks of the San Juans. But I really wanted to know we were both safe.

Choosing the High Route

The complications began immediately. At the base of an unstable boulder field, where the rocks gave way to Pole Creek’s marshy outflow, I saw the same 10.5 Speedgoat tracks headed up the slope I was descending. Tina, I assumed, had recognized she’d followed the wrong footprints to the lower trail. She had then reversed course to the high route, ostensibly missing my waiting backpack by a few hundred yards while I frantically looked for her. She was indeed ahead of me, but, once again, on a different route. I decided to stay low, cruising through the valley on a bluebird day, a welcome counter to my anxiety.

Just before 5 P.M., I reached our potential 21-mile campsite, Beartown Trailhead, a postage-stamp parking lot cut into a ragged road alongside a ghost town. Tina wasn’t there, and she had not yet signed the journal at the trailhead. I climbed a fallen tree that afforded a commanding view of the ridge I expected her to descend at any moment. The sun sank steadily; after an hour passed, the light dwindled. The only blots of black I had seen were a grazing bull moose and a bounding bear. I needed to go looking for Tina, to make sure we ended up at the same place that night, in the same tent, since neither of us actually had a complete one.

I pushed north on the high route for two hours, climbing a pass until I could scan the horizon for headlamps. There were none. I called her name, again and again, losing my shouts to the rush of early winter wind. “And now it is now, and the dark thing is here,” I thought, remembering a line from a Louise Penny whodunit I’d just read on trail. This was the nightmare scenario, the dark thing.

Pulling myself together, I turned around, sprinting south in the dark toward the trailhead where I’d hoped to meet Tina. Maybe she had actually gotten there first and pressed on to our proposed second campsite at 25 miles? It was nearly 10 P.M. now, the temperature dropping deep into the teens at 12,000 feet. But still, I had to try, even if climbing another 800 feet and descending 1,100 more across a mountain mounded with snow would take until midnight.

As I grunted my way up, I finally understood desert oases: Every star hovering above the ridge looked like Tina’s headlamp, every antenna flashing in the distance to another place I might yet find her. Looking over my shoulder, I did indeed spy two lights on the ridge I had just descended, advancing unsteadily toward the parking lot where Tina and I were supposed to meet. That was her, I told myself. She had found one of our friends, and they had continued deep into the night, looking for me. She would get there, find my note in the trail log (“Tina: Nebo,” as in Nebo Creek, the 25-mile campsite), and find me at first light.

It was almost midnight, and I was almost sleepwalking. I made it to Nebo Creek, stretched the tent on the ground, put on every layer I possessed, crawled into my sleeping bag, and wrapped the arms of the tent around me like an awkward waterproof jacket. I slept until 4 A.M., shivered my way toward sunrise, and then, once again, waited for Tina.

Shifting to Emergency Mode

Tina never made it to Nebo Creek or Beartown Trailhead or the ridge onto which I’d raced and howled her name.

Nearly every hiker had dropped off the high route that morning, cutting instead through the valley. She was one of only five hikers to work across the snowy peaks that afternoon, helping break trail at around a mile per hour. Around 3 P.M., she found Ezra and Encore, two of our closest hiking friends, and asked how far ahead I was. But there were no footsteps ahead of their own. Collective panic set in. As the sun set, Tina sidled into Ezra’s ultralight tent, so small it doesn’t have a door. They slept fitfully, wondering when I might hobble into camp, or if I was even capable of hobbling.

When the sun rose, Tina and I separately intuited it was beyond time to shift into real emergency mode. Her triumvirate broke camp and quickly moved three miles south, to the gravel road just south of the San Juan’s stunning and famed Stony Pass. They turned toward Silverton, another Colorado mining locus that now draws droves of tourists with its narrow-gauge railroad and the Hardrock 100, and hitched into town. The moment they hit cell phone service, for the first time in more than 48 hours, they filed a missing persons report. I was their missing person.

But Tina was my missing person. I had no easy way out to town, and I had not seen another hiker in at least 24 hours. It was time to pull the technological ripcord: send an SOS, if I could figure out how. Because we’ve always been so close to one another on trail, Tina and I have rarely used a Garmin inReach or the like. They’re bulky and expensive, and they just seemed unnecessary. A year earlier, though, we had both purchased an iPhone 14 before beginning the Arizona Trail. Their much-ballyhooed satellite addition—essentially, allowing you to text emergency services and transmit your location via satellite—offered a last resort should we never be able to help one another out of some sort of mortal fix, like right now.

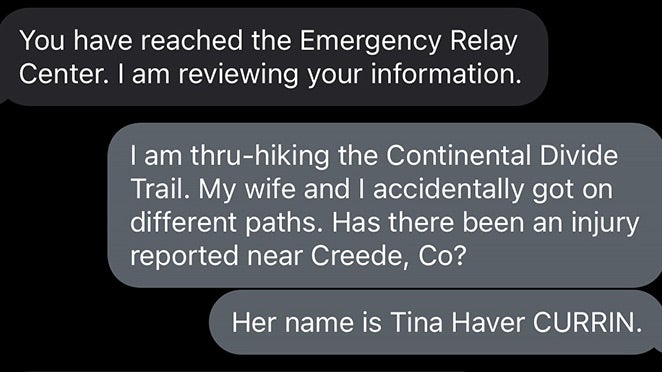

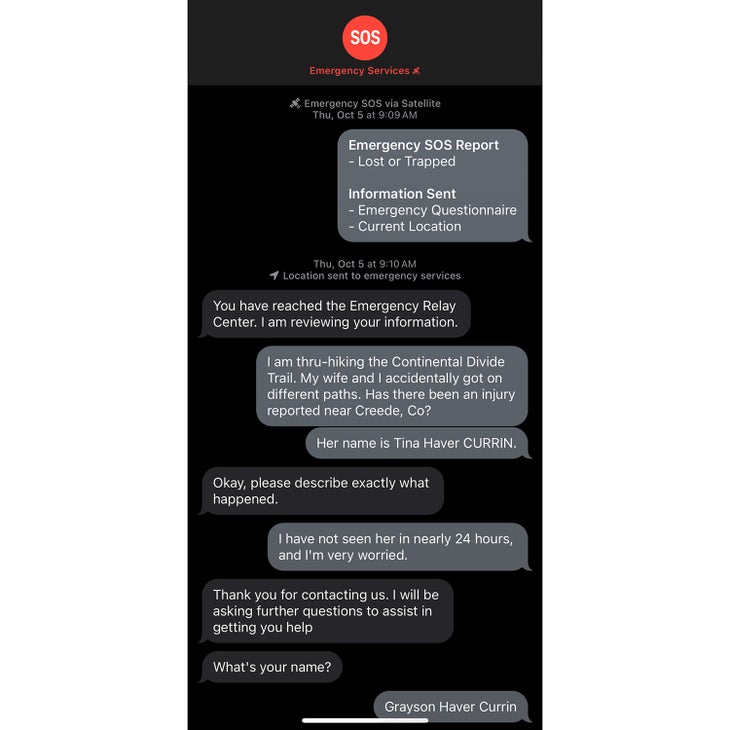

With shivering hands, I started the demo, learning to trace the horizon above the canyon walls with the top of my phone to track satellites. The display guided me through an example conversation with emergency services. Finally, I was ready to try it. “I am thru-hiking the Continental Divide Trail,” I typed at 9:10 A.M. “My wife and I accidentally got on different paths. Has there been an injury reported near Creede, Co?”

There was some seemingly inconsequential back and forth, fastidious questions about intended routes and last known locations and dates of birth. After 20 minutes, I was ready to give up and start walking again, to head south toward a blip of cell phone service I knew existed on a peak in 13 miles. And then, at 9:40 A.M., the good word came: “Your wife is not injured and emergency services are working on getting her location,” the person at the other end wrote. “Please stay where you are while we get your wifes location.”

I cried for the first time in 2,000 miles. Then, yet again, I waited.

Dialing SOS

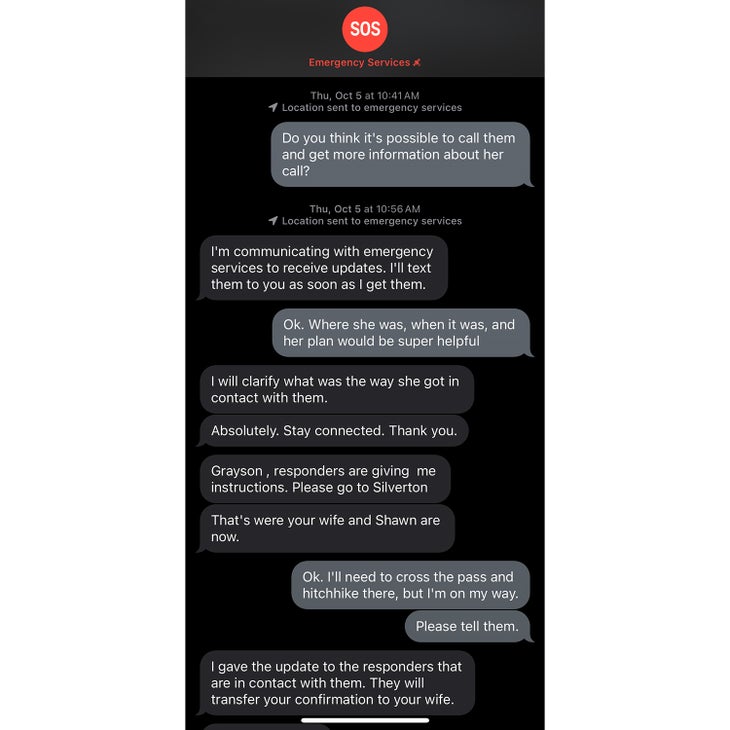

After an hour of back and forth with assorted agencies talking to Apple and vice versa, I finally had marching orders. Tina was in Silverton with our friends, Ezra and Encore, waiting for any word from me at a hostel. Finally, they received an update: “He has thrown an SOS,” an emergency worker told Tina, vaguely. She knew I was alive, but little else. She was powerless.

To reach her, I had to cross nine miles and 5,000 feet of gain and loss over always-difficult terrain that was now blanketed in mostly unbroken snow. And if I wanted to make it by sunset with the possibility of catching a ride into Silverton, I had less than six hours to do it. It was the hardest hike of my life, a maddening series of skids down icy creek banks and face plants in snowdrifts of several feet, along with a snapped hiking pole and a cut face. The creature-laden swamps of Florida, the endless river crossings of the Gila Canyon, the waterless haze of Wyoming’s Great Divide Basin: I’ve never been challenged by a trail like that.

But at last, I reached the road below Stony Pass, only to find that all the cars had left the busy trailhead as the sun dipped below the horizon. No one else was coming. I would either need to spend the night again near 13,000 feet with no tent or find another way down. Walking felt like an expressway to hell.

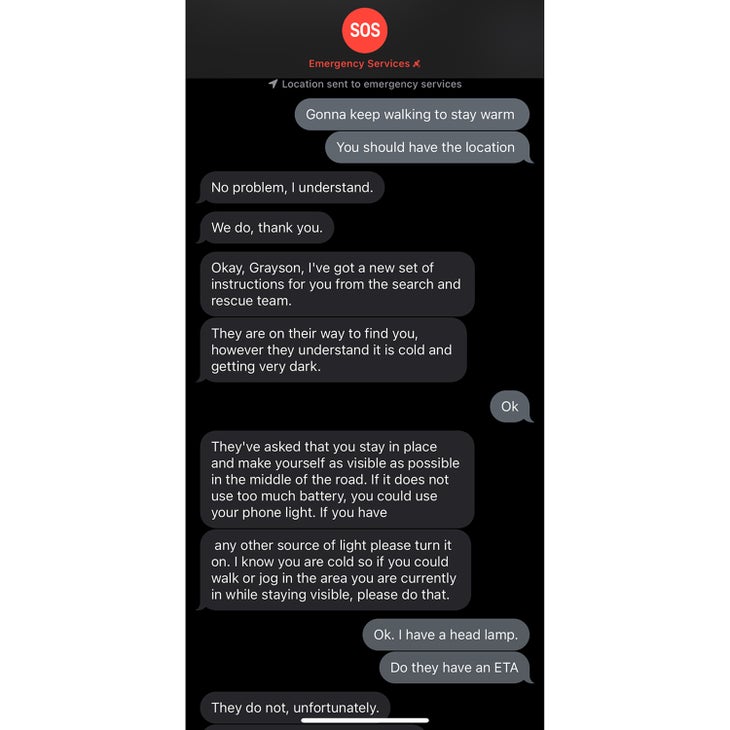

I’ve always been drawn to the self-reliance of thru-hiking, the way you carry your food, shelter, and clothing on your back, the way you only ask for help if you absolutely need it. I needed it: I found the satellite signal again, logged back into the emergency chat, and asked for a ride. Fabian, the new person on the other end, told me he would dispatch a rescue team from Silverton, but it could be hours. I walked down the road until Fabian told me to stop, then climbed inside my sleeping bag. Dark set in.

And at last, I heard a siren echoing off the canyon walls below, lurching toward me. I stood up, flashed my headlamp, and told the two men inside the warm SUV what day of the week it was after they asked. The ride down was as bumpy as a wooden roller coaster on the verge of collapse, but I beamed the entire way.

When I walked into The Avon hotel and climbed the stairs at 8:30 P.M., 37 hours after I’d last seen Tina, I found her pacing the hall. “Let’s eat,” I said before she saw me. She turned, stunned. All day long, she’d heard nothing else about where I was, how I was, or when I might show up. Arms around one another, we both cried again and then, of course, ate pizza at the nearest place we could find.

A Phone to the Rescue

Early into the CDT, we bought a house in Colorado, sight unseen, high in the mountains just a few hours north of where I worried Tina had died or I might die. We live here now, having settled in a week after we finally reached the Mexican border, 800 or so trail miles south of what I’ve taken to calling “the incident.” We took two days off, rested our brains, and then pressed into New Mexico, racing through it without pausing for more than a night in a hotel.

It is easy, sitting here in the warmth of an office as snow mounds beyond the glass, to armchair quarterback our decisions on that day or at large. Should we hike with Garmins? Maybe. Should I have climbed back to the high route? Possibly. Should I have hiked all night to find Tina, until I got to her camp above Stony Pass? I have considered that option dozens of times now, and I still think it’s a terrible option. Did I need a lift from the SAR team? Looking back through some shame, I wish I would have walked into town, no matter how long it took.

But in the final tally, I am comfortable with everything that happened, however uncomfortable those things were. Survival is a series of choices, weighted coin tosses with varying degrees of uncertainty. Twin Garmins would have eliminated some of that risk, as would never hiking in blissful solitude, where the mind may roam far beyond the reaches of the body. But our sport is often about finding the edge of what it means to make it, then riding it for as many miles as you can. We made it long enough to hike another day, to learn our lessons and to carry on.

Had it not been for those satellites ringing the earth, though, I don’t know if I would have. The worst decision I could have made would have been to continue south, hiking deeper into winter’s alpine arrival with no usable tent and no one with whom to strategize. Remembering my desperation that morning, it is, however, likely a mistake I would have made. Those emergency texts told me to turn around. They may have saved my life.

Apple’s satellite feature has room for improvement. Two Garmin inReaches can interact without a satellite signal, allowing users to send messages to another without cell service, while an iPhone cannot. That ability would have made all the difference, and I have to suspect it’s coming. And despite my repeated pleas, the emergency service personnel never told Tina anything about my location or condition, a simple and humane act that would have made her wait all the more bearable. So, no, it’s not perfect. But obviously neither am I, the idiot who got stranded in the San Juan Mountains with a cell phone without service and a tent with no tent stakes.

Source link