No products in the cart.

Outdoor Adventure

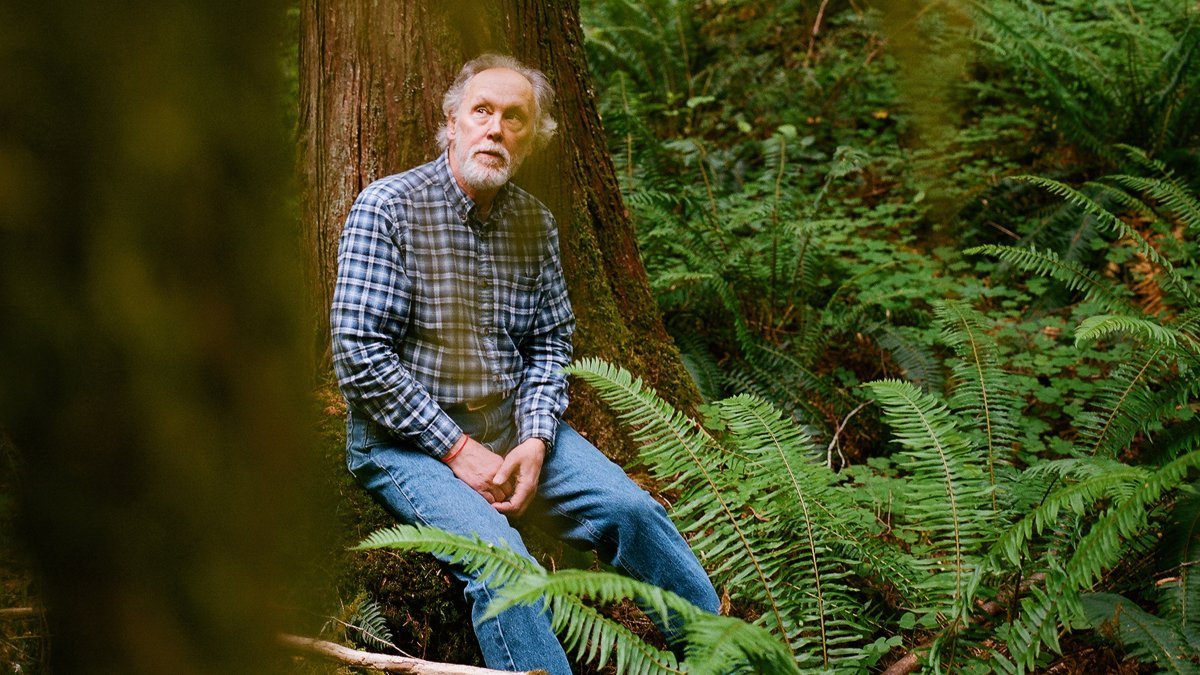

Remembering My Friend Barry Lopez

I have a friend who for many years wrote obituaries in the New York Times. He became very good at it, but it is an art I hope to never master. The breadth and depth of extraordinary lives—most everybody’s full life—at first seems overwhelming but then must be stewed down into a list of finite achievements, necessary but necessarily shallow.

It strikes me that sometimes, for some truly iconic lives, the simplest obit would be best, something that might read like this: Man. River. Fire.

In this instance, the man would be the writer Barry Lopez, whose comparisons to the luminaries in the American literary pantheon—Henry David Thoreau, John Muir, Rachel Carson, Aldo Leopold—are not hyperbole, for Lopez was in every way an heir to the genius of their labors, and by that measure he was and will remain a national treasure.

The river would be Oregon’s McKenzie…or any river in the world that you feel some deep attachment to. And the fire would be the Holiday Farm Fire that ravaged western Oregon in the summer and early autumn of 2020…or any other evidence of the catastrophic consequences of global warming.

As for Barry’s death itself, we have two dates to choose from: September 8, the day the fire came over the mountains and down toward the river, or December 25, the day he stopped breathing. Born on Epiphany, 75 years ago; died on Christmas Day. The true truth is always metaphorical, Barry once told a friend, and his greatest belief was in the power of stories, and these seem to be the paths to follow here.

Unless we are simpletons, we are all to some extent paradoxes, and Lopez was both an indefatigable traveler and, as writers must be, a monastic homebody. The man who found the time to travel and work in 80 countries lived in the same house for 50 years, an hour up the road from Eugene, where he had come in his early twenties to get an MFA at the University Oregon. (He didn’t get the degree.)

A rare piece of permanence in a voyager’s life, the house was wood-shingled and gabled and mossy, in a rainforest grove of everlasting shade cast by towering Douglas firs, in a ferny compound clearly managed by a guy obsessed with stacking firewood. The illusion of its Tolkien-esque isolation was fractured by its scary close proximity to the McKenzie Highway, a north–south artery thundering with logging trucks and sclerotic with tourists. On the far side of the pavement, though, flowed the exquisite McKenzie, and when the road was quiet, you could hear through the open windows of Barry’s study the hooting snatches of ecstasy of the river runners in their drift boats, carried off swiftly in the current.

The property remained much the same for decades until 2007, when Barry married a former student of mine, Debra Gwartney, herself a formidable writer, and she moved into the house, which had, I suppose, adequate space for one author but not enough oxygen for two, so her husband built her a beautiful studio about 50 yards from the kitchen door. I think my wife and I and our three dogs were the first guests to be housed in the studio, on a visit in the summer of 2013. Our last night at dinner, when we asked if he could suggest a wild stretch of coastline where we might camp unmolested the following night, Barry, with a gush of nostalgia, recommended a place called Horsfall Beach, where he had often pitched his tent in perfect solitude back in the ’70s.

In the morning, Barry wandered over to the studio’s deck to sit with us during breakfast, and we discussed with increasing excitement and intensity the book he was working on, which he described as a 65,000-year-long autobiography—65,000 years being, at that moment, the best scientific judgement for the emergence of Homo sapiens, before they began to spread out into Europe and Asia and, woe unto this day, intermingle their genes with dumbass Neanderthals. I’m not sure what happened to that book. I suppose it morphed into the next one, Horizon, his last, the 17th, which would be published in 2019. I recall during our conversation that I had a profundity to offer. Barry’s gimlet eyes said Wow! and he wrote it down. I forget what it was, but you might well imagine he was always writing things down—a habit more significant than any particular thing I might have said.

After breakfast, we packed up and went over to the coast, to the highly recommended Horsfall Beach, which, if Barry had ever set foot on since 1975, it was only in a nightmare. Multiple dozens of little shits and big beer-bellied shits and gray-haired ma and pa shits blasted and corkscrewed and fishtailed through the dunes on $10,000 ATVs. The sun was going down, and we were stuck, apologizing to our dogs, who deserved better after our long haul from New Mexico to the Pacific.

Ah, Barry, I laughed to myself, this is what comes from having the equivalent of the Hubble telescope for a pair of eyes. You end up seriously farsighted, focused on the mysteries and panoramic wonders, with a nearsighted myopia to the flaws in the frame. These little blind spots, WTF specks of cognitive dissonance: that fucked-up highway; that horror of a desecrated beach. After living in that house for a while, Debra finally said to herself, “You know, that river’s not just to look at,” and rented kayaks, something Barry had never done.

He loved the wind in his face—subzero was just fine with him. He loved to watch, observe, witness, listen, report, struggle to see, struggle to understand.

His mind was always locked into the gifts. He loved the places most that were existentially scary—the desert, the ocean, the Arctic, where he lived for five years. “It’s the big open that engages me,” he once told an interviewer. “It’s a bare stage for me to work on.” He loved the wind in his face—subzero was just fine with him. He loved to watch, observe, witness, listen, report, struggle to see, struggle to understand—he was a National Geographic Explorers Club–class adventurer who wasn’t interested in adrenaline or thrills. The rush for him was of the mind and spirit, not of the flesh, and yet for 50 questing years he did the wildest things, smitten by the tastes and the smells and the music of the elemental world and its species and its tribes.

Those amusing transgressions I mentioned above provide a sort of bridge to something of the greatest seriousness: Barry’s integrity. He was a man who insisted upon a level of individual responsibility that shared in the blame for what was happening to the planet. One thing I always appreciated about Barry was that he did not hesitate to implicate himself in the trouble. To pretend you knew better when others didn’t, to pretend this was not your fault, to pretend you were a holy messenger and everyone else was a fool was his very good definition of a sin. We have painted ourselves into a corner. Everybody, Barry rightly insisted, held a brush. We all know the cliché: Can’t see the forest for the trees. Lopez understood that its truth works just as well in reverse. Those many years ago he had walked away from Horsfall Beach and into the farthest reaches of the world.

That morning at breakfast, which is the last time we saw Barry, we told Debra and him the quick story of our unrestful night in her lovely studio. “Did you hear it?” we asked. “Hear what?” they said. “Really, you didn’t hear that alarm going off all night long?” we said with disbelief.

“What alarm?”

After we fell asleep, the fire alarm in Debra’s studio had started going on and off randomly throughout the night. Just as we would start to fall asleep, it would blare for a minute or two and then stop, and we were helpless to fix it. It was so loud we thought they must hear it in the main house.

“What alarm? The fire alarm! The fire alarm!”

“Nope.” They both shook their heads. “Never heard it. Didn’t know that alarm had a ghost in it.” Never heard it again, even though it surely sounded again, when the firestorm raced down the valley. But by then they were gone.

In the late 1970s, Lopez began publishing, and the books came in a flurry—three collections of fiction and fables: Desert Notes: Reflection in the Eyes of a Raven (1976); Giving Birth to Thunder, Sleeping with His Daughter (1977); River Notes: The Dance of Herons (1979); and the critically acclaimed work of nonfiction, Of Wolves and Men (1978), which was a finalist for the National Book Award.

I’m not sure which book he was reading from when I first met Barry in 1978, as we walked together out of the auditorium at the University of Missouri, where I was in grad school. I wanted to write fiction, which was what Barry was reading, and he had wrapped me in sentences like cords of luminosity. His lyricism and his textures were sublime, and he woke me up to my own desire to paint these same strokes with words. He made language as potent as science in penetrating the mysteries. For a writer who would become most renowned for his nonfiction—he won the National Book Award for Arctic Dreams in 1986—it was his short stories and fables and trickster tales that I most cherished, learned from, stole from.

The next time I saw Barry was years later, more than ten, and by that time my own work had become a presence on the literary scene. We were both working for Outside and Harper’s, and Barry really stunned me by treating me like a long-lost friend. In fact, Barry seems to have been good friends with just about every soul he ever met across the planet. It’s no exaggeration to say he connected with everybody, at every level. It was never only his writing that attracted people to him—it was his radiant humanity, his true respect for others, especially those who could teach him what he most wanted to know: How do we live together, not just with each other, but with the earth?

I don’t think I’ve ever personally known a man or woman who was so loved by so many.

The books kept coming; the stream of articles and essays never abated. The lectures, the keynote addresses, the honors and awards piled up, and yet, like with the scientists themselves, there was a sense that his work was underappreciated, that as a society we were not extending the right amount of attention to what Barry and his peers were telling us about how the earth was changing, about how urgent it was that we begin to reimagine the world and our place in it. To explain what he intended as a writer, he would offer a metaphor of migrating birds.

“Geese fly in a classic V formation,” Barry once told me, “with an undisputed leader, everybody else following behind. If the leader somehow fails, so does the flock. Cranes, however, migrate in undulating lines, spread out on a horizontal axis, with no true leader, everyone simultaneously searching for a thermal to make the labor of their journey easier, and when somebody in the line finds a thermal—and therefore vision—everybody zeros in and benefits.” There’s no better metaphor for an artist’s role in society.

Any dinner table discussion with Barry inevitably turned to the dynamics of telling a story. He had spent weeks and months and years among the traditional Indigenous cultures of the far north, trying to learn what they have to teach us, trying to understand the role of the writer in society. “It’s a mistake to tell all the stories of all the people,” Barry would tell you. “The question of quantification is not useful. The distinction is between inauthentic or authentic.”

Barry once told me about a question he asked tribal elders in traditional cultures. “‘What do you mean by a storyteller?’ They answered, ‘When the stories you tell help’—and it has to do with your mature perspective on what in fact helps and what diminishes that dynamic in a society or an individual. The question ‘Is it helpful?’ is ultimately a community decision.” For Lopez, writing was an essential act of community, no matter that it was born and executed in isolation and self-exile. The point you had to come to, he emphasized, was this: Am I alone after reading this story? With any great writer, you never touched bottom, and you never felt alone.

During our visit to Finn Rock back in 2013, Barry told us the news we never wanted to hear: He had been diagnosed with prostate cancer and would be starting an array of treatments later that summer. But by the end of August, the prognosis had darkened. “It is bad news,” Debra wrote us, “but we find ourselves feeling oddly hopeful.” The cancer had metastasized, moving to his bones and lymph nodes. “But you well know Barry’s deep determination,” Debra wrote, “when he gets his teeth into an effort.” Overnight, she became the diet Nazi, depriving him of his beloved coffee and much-adored sugar, adding kale and turmeric and fish oil to everything.

Years ago, one of Barry’s cherished mentors had told him, “The only thing to understand is that you can never quit. You can’t ever say, ‘Well, this is hopeless.’ We’re all going to go down the tube.”

His expiration date should have been up soon after his diagnosis that August, but in the ensuing years, I never heard a word about Barry slowing down. He had made for himself a life that leaned into the light, but neither was he a stranger to darkness, and he was determined to keep going. He and one of his best friends, the writer David Quammen, talked about endings, just disappearing on a plane that goes down in some jungle somewhere, the fantasy of aging sojourners, but Barry, when I checked in, was always in some airport lounge, headed out, or being touted in New York, or over lecturing in Lubbock, where his archives were housed in Texas Tech’s Sowell Collection. In the outbuilding on his property that served as a repository for his books and manuscripts, he had one remaining load of boxes destined for the archives, which he planned to deliver himself, driving down to Texas in the spring of 2020, but COVID-19 interrupted that trip, and the folks at the university said let’s wait until next year.

On the night of his first death, September 7, 2020, burning into September 8, Barry and Debra anxiously watched the eastern sky before they went back into the house and to bed and to sleep. There was a sinister orange aura rising above the ridgelines and a baking wind blowing down the banks of the McKenzie. Around midnight, they were awakened by a firefighter banging on their door, who told them they had five minutes to evacuate. “It was hellish,” Barry texted friends. “No warning. We just ran.” They grabbed the cat and Debra’s wallet and that was it, nothing else. Outside, they could see the flames advancing over the ridge behind the house. When they drove away, the life they would return to three weeks later would be nothing like the one they left behind that night as they escaped to Eugene. The house and Debra’s studio were still standing, though severely smoke damaged, but the archive shed housing the rest of Barry’s papers had burned to the ground. All the other outbuildings were lost and, most cruelly, his beloved truck, the one he dreamed of taking to Texas on his last road trip.

It was now October, and the fire had come for Barry, too. You want to say that the erasure by wildfire was ironic, but from a better angle it seems like a perfect last piece found and inserted into Lopez’s own cosmic puzzle. While the mind rushes to the irony of the event, the heart seems to understand the correctness of the devastating moment, which is not ironic. Nature never loses. Whether you’re trying to destroy it or save it, the whale wins.

Just a handful of days ago, Barry awoke in his bed early on Christmas Eve and looked around at his gathered family, his four beloved stepdaughters and Debra, and said, “It’s a wonderful morning. How is everyone?” Fresh air was blowing through the window, and the room was filled with mantras of love. Those were Barry’s last words, as if he were Mr. Rogers, but for this man, the neighborhood he called his own went to the horizon and beyond. His passing the next morning was gentle, Debra said. They washed him with water from the McKenzie River and wrapped him in a buckskin and Pendleton blanket. A future son-in-law built a handsome pine coffin with cedar trim and beaver-stick dowels, in which they laid him out on New Year’s Eve and filled it up with things he loved and flowers and ferns and flora that was already growing back on their fire-scarred property, and then his daughters had the sacred duty of pushing him into the furnace and back into the flames, and from there, in the hands of Debra and the girls, he would find his way down to the river.

For just this moment alone, you would have to say he was a lucky man.

Support Outside Online

Our mission to inspire readers to get outside has never been more critical. In recent years, Outside Online has reported on groundbreaking research linking time in nature to improved mental and physical health, and we’ve kept you informed about the unprecedented threats to America’s public lands. Our rigorous coverage helps spark important debates about wellness and travel and adventure, and it provides readers an accessible gateway to new outdoor passions. Time outside is essential—and we can help you make the most of it. Making a financial contribution to Outside Online only takes a few minutes and will ensure we can continue supplying the trailblazing, informative journalism that readers like you depend on. We hope you’ll support us. Thank you.

Lead Photo: Annie Marie Musselman

Source link