No products in the cart.

Outdoor Adventure

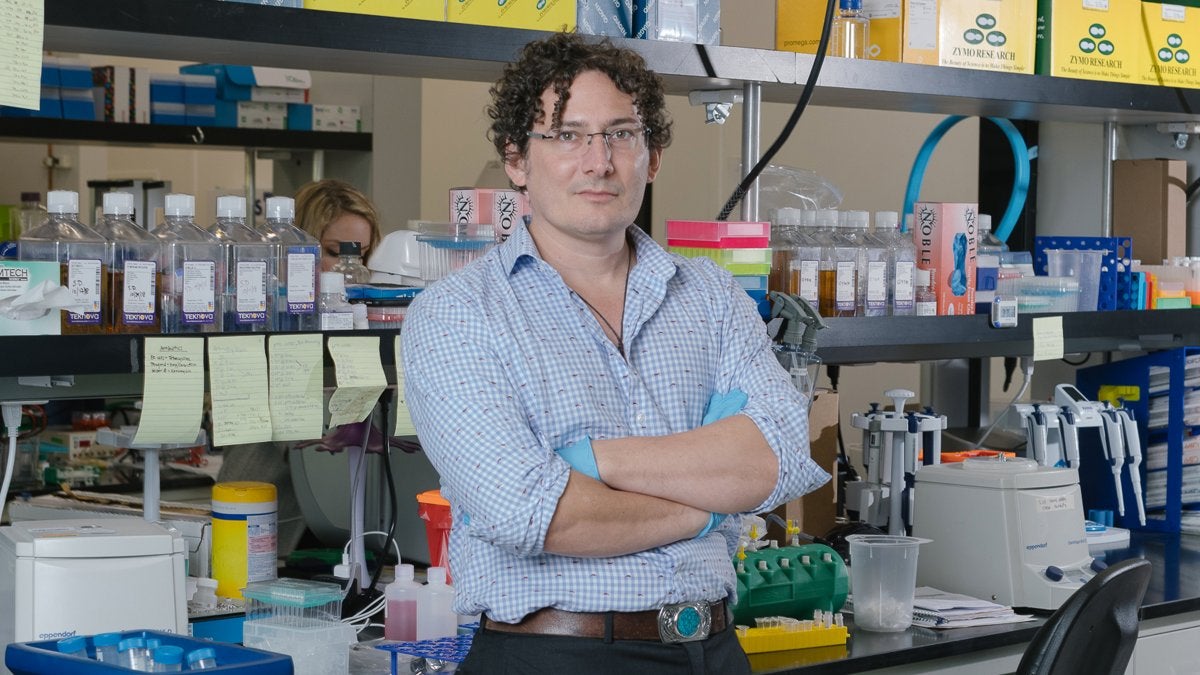

The Antibody Avenger and the Quest for a COVID-19 Cure

To remind herself that hurried work can have consequences, the anonymous virologist I interviewed keeps a quote on her office wall from Richard Feynman, the Nobel Prize–winning physicist. As a lesson in drug development, she often tells the story of Feynman’s devastating conclusions about the 1986 explosion of the space shuttle Challenger. It’s set during an inquiry about the disaster. During a famous line of questioning about the dangerous disconnect between the caution of NASA’s engineers and the ambition of the agency’s management, Feynman took out an O-ring that engineers had identified prelaunch as a part that could fail catastrophically, especially in freezing temperatures. He dropped it in ice water and the part failed. “For a successful technology, reality must take place over public relations,” Feynman said. “For Mother Nature can’t be fooled.”

“Data is king,” the virologist says, echoing Feynman. “In my field, a drug is either going to work or it’s not.”

Basically, she thinks that Glanville, who has yet to publish any results from his coronavirus research in a major scientific publication, has oversold the importance of discovering antibodies that can neutralize CoV-2 in a dish or a hamster, even though he’s succeeded in doing both. In experiments with hamsters, Glanville’s antibodies reduced viral load by 97 percent in rodents that received the drug as a treatment, and even more than that when they were given prophylactically. The virologist says this is a good start, but it still doesn’t demonstrate the ability to neutralize the virus in people; it doesn’t show whether the treatment can cause dangerous side effects; and it doesn’t reveal how much to give in a dose, where and how the dose should be administered, whether the antibody actually disperses to the parts of the body that harbor the virus, and whether the drug can even be manufactured.

“That’s the problem with biology,” says the virologist. “It gets more and more complicated the deeper you get into drug development.” Between the discovery of an antibody, even a potent one, and the development of an actual drug, there is a gauntlet of manufacturing and safety hurdles that, because of the expertise and money needed to navigate them, giant pharmaceutical companies are better equipped to clear. Although Glanville’s team includes researchers with experience shepherding antibodies from discovery to the marketplace, he is having to learn the bureaucracy of drug approval on the fly. His public optimism, the virologist argues, may be dangerously and even cruelly misleading to those outside the industry.

Glanville is now one in a crowded field of researchers trying to improve antibodies’ efficacy against COVID-19. By late 2020, there were at least 21 other monoclonal antibodies in some form of clinical trials, including five knocking on the door of FDA approval in phase three. And after watching the mixed success of the leading antibody drug manufacturer, Glanville decided to to stop trying to emulate the front-runners. Regeneron, the multibillion-dollar company whose antibody-based drug was approved for emergency use by the FDA in late November, took all the right steps, but its drug is far from the effective cure it hoped it would be. Before the FDA granted its final approval, early results suggested it could be hugely successful. Because of this, doctors gave an experimental version of it to President Trump, who claimed that it cured him, despite there being no scientific way to know this, since he received several treatments at once.

What has become clear is that Regeneron’s cocktail, like Eli Lilly’s drug bamlanivimab, only works well against milder cases of COVID-19. These drugs aren’t being widely used by hospitals, because when people fall critically ill, even massive doses of the antibodies delivered intravenously do little to revive them. Antibodies only target the virus, and once an infection is established, there is simply too much virus for the administered antibodies to control, and they can do nothing to tamp down the symptoms that ultimately cause death. This fact, plus issues related to storage and cost, explains why many in the industry no longer pin their hopes of taming COVID-19 on antibodies.

That Glanville’s competitors haven’t been huge successes might seem like a good reason for him to abandon his project. So, too, that by midwinter no agencies or private investors had come forward to fund his efforts, despite almost a full year of persistent, exhausting, and ultimately deflating lobbying efforts. By early March, Glanville estimated he’d met with almost a dozen government agencies funding COVID research, from the Army and Navy to Operation Warp Speed. The Gates Foundation turned him down. So did a handful of other big-dollar foundations. He raised only $9 million, barely enough to get his antibodies through animal trials. The challenge seems to have only hardened his resolve. Reality, he says, is driving him forward. “Very rarely in the history of pathogens have we vaccinated enough people worldwide to eliminate them,” he says (smallpox being the lone example). “COVID is here to stay.”

When CoV-2 first infected a person somewhere in rural China, the new bug was far stickier to the ACE-2 receptor. For the virus, it’s hard to imagine a better evolutionary move. For a human, it’s hard to imagine one that could be worse.

Glanville maintains that his antibody is one answer. His sales pitch is as convincing as ever: an antibody potent enough that doses can be smaller; capable of being delivered in a shot rather than an IV; engineered to cause fewer side effects in the immune-system response than his competitors’; and, because it targets a part of the virus that hasn’t changed even as the human pandemic has spawned new viral mutations in Brazil, South Africa, and England, effective against new variants. True to his Robin Hood style, Glanville also wants his drug to be widely available and relatively cheap. He has mapped out a sort of Walmart distribution method for his drug, a model in which bulk production will keep the price down. Instead of $2,000 a dose, it will be $800, maybe $900, but certainly “less than the cost of an iPhone,” he says. (Glanville isn’t alone in his pharmaceutical goodwill. AstraZeneca is trying to sell its vaccine for $4 a dose.) Driving the cost savings for Glanville is smaller overhead—30 employees versus 30,000 at a company like Eli Lilly—and a novel manufacturing approach. Glanville had a team of interns identify more than 500 companies around the world with bioreactors that are capable of brewing his antibodies. Instead of cooking drugs through in-house bioreactors or subcontractors with restrictive terms, as the big companies have done, his plan is for many hands to make light work. By increasing supply, Glanville will fill the need and lower the costs.

The virologist who asked to remain anonymous is unwaveringly skeptical that this will play out as Glanville is willing it to, especially with so many researchers on pace or way out ahead of him. “Skeptical is the safe bet,” Glanville said of her take. “Odds are we fail.”

And that looked to be his antibody’s fate. But then, in early February, Glanville got a few pieces of good news. He refused to call them unexpected. The first was that Nature Biotechnology, an esteemed journal in his field, agreed to publish his work on the coronavirus. And in late February, Merck bought Pandion for $1.9 billion. The significance to Glanville was that Pandion used his patented technologies for some of its drug-discovery work. The announcement demonstrates that antibodies he has designed have clinical value. Most exciting for him is that he is finalizing an agreement with a federal entity—which he won’t name until the deal is final—that will fund his phase-one research.

Whether his antibody becomes a drug or not, entering the race to find a COVID-19 treatment clarified for Glanville why he got into this business—to help people. To that end, in the first week of January, he and his partners sold Distributed Bio to a much larger pharmaceutical company called Charles River Labs for more than $100 million. He’s since founded a new firm called Centivax that will focus solely on making therapeutic drugs and vaccines and getting the ones he’s already developed to market. “The time is nigh,” he says. “This work needs the best version of me possible.” As such, at 40, he quit drinking and started swimming in the ocean each day. To get just enough of the altered reality he needs to maintain sanity, he smokes three cigars daily on his rooftop office, looking out over the ocean and thinking about where the next bad bug might emerge.

Source link