No products in the cart.

Outdoor Adventure

This Super Steel Is Revolutionizing Knives. Is it Worth The Price?

If you go shopping for a premium knife right now, you’ll find a new word plastered across online retailers and local shops: MagnaCut, a new type of blade steel that’s dominating the market all of a sudden. Now, MagnaCut is being used to justify some astonishing prices. So I set out to learn what it is, how it performs, and whether or not it’s worth the premium. And because I’m just a casual knife enthusiast rather than an engineer or craftsman, I set out to do that in terms us normal people could understand.

“MagnaCut has generated quite the buzz due to its toughness, edge retention, and corrosion resistance,” explained Morgan Keenan, who produces handmade knives in Bozeman, Montana for his brand Cudaway. “Typically it is very difficult for a steel to excel in all three of those categories. One that is very hard, and able to hold an edge very well, tends to be more brittle. A steel that can bend and take a beating tends to be softer. Stainless steel that can do all that without corroding? It’s just a game changer for the knife world.”

“A user will experience a steel that resists rusting, holds an edge well between sharpening, and is resistant to edge rolling and chipping,” Larrin Thomas, the metallurgist who invented MagnaCut, told Outside.

“Generally speaking, you can maximize two of those things, but not the third,” said Peter Parker, Lead Design Engineer for Leatherman. That brand just released a new flagship multitool called the Arc, which justifies its $80 premium over similar tools thanks to the incorporation of a MagnaCut blade. “If you make a knife that doesn’t corrode, then it doesn’t hold an edge. Stainless is not as great as carbon steel at holding an edge. But then carbon steel corrodes. With smart and clever metallurgy [Thomas has] found a sweet spot in the chemical composition that hasn’t been done before.”

MagnaCut is produced by Crucible Industries, a New York-based steel manufacturer. The company’s specialty is a powder metallurgy process—known as Crucible Particle Metallurgy—which Thomas explains allows for fine control of a steel’s molecular properties.

“The liquid steel passes through a nozzle which is sprayed with nitrogen gas to instantly solidify the steel into fine particles,” Thomas describes. This gives steels, “a much finer microstructure for more consistent properties.”

It also allows metallurgists like Thomas to tinker with precise ratios of different compounds in a steel alloy, and how they interact with each other.

“Stainless steels have high chromium, forming chromium carbide with the high carbon necessary for high-hardness knife steels,” explains Thomas. “The best non-stainless powder metallurgy tool steels only have the hardest carbide types, typically vanadium carbide. The powder metallurgy keeps the carbides small for good toughness, while the very high hardness of the vanadium carbides provides wear resistance. Chromium carbides are smaller and so do not provide as much wear resistance, while being similarly detrimental for toughness. More carbide means more wear resistance but lower toughness because they are hard, brittle particles. A harder carbide provides a better combination of wear resistance and toughness. Therefore, the combination of wear resistance and toughness was better for the non-stainless steels.”

“MagnaCut uses a unique approach where the chromium content was reduced and the other alloying elements balanced so that chromium carbides are avoided and it has the same properties as non-stainless steels,” the metallurgist continues. “Removing chromium carbide from the microstructure also improved corrosion resistance versus other stainless steels. Stainless steels get their corrosion resistance from a chromium oxide passive film at the surface. If the chromium has already formed a bond with carbon, it is not available to form the chromium oxide. MagnaCut avoids this issue, so it has both better corrosion resistance and a better wear resistance-toughness balance than prior stainless knife steels.”

I asked Keenan to put all that in plain English. “What makes stainless steel ‘stainless’ is the amount of chromium in the mix,” he explains. “But this chromium can bond with carbon creating carbides and negating the corrosion resistance and ‘stainless’ property. “The beauty of MagnaCut is in the mix, there is just the right amount of carbon to keep all of the other elements of the mix in carbides, and the chromium is able to maintain the stainless properties of the steel.”

Before developing MagnaCut, Thomas worked on automotive alloys, while writing about his passion—this history of knife steel metallurgy—on his blog: Knife Steel Nerds. One brand that was heavily inspirational in his work used to put the word “cut” after the name of its unique alloys, so Thomas wanted to pay homage to that naming convention with his first knife steel.

“I named the steel MagnaCut, Magna being the Latin word for great or awesome,” he says.

Leatherman’s Parker notes that MagnaCut does have a downside. “It’s kind of expensive, that’s the tradeoff,” he explains. “All this awesome stuff doesn’t come for free.”

Parker says that the powder atomization process and heat treatment for MagnaCut cost about the same as any other premium steel, but that there’s more costs on the manufacturing side.

“Once we have it in the factory, it’s really hard to grind and process it,” he says. “It doesn’t wear out when the consumer is using it, but it also puts up a fight when we try and make these to the Leatherman quality standard. It’s hard to make it uniform from side to side. You tend to get one side that looks different from the other because you have to push on it so hard to grind the material. That means the tooling has to essentially be pushing harder to the metal which makes things flex. You’re battling the material.”

Still, “this is a massive step in the knife world,” says Keenan.

The Best MagnaCut Knives

For The Kitchen: Sitka x James Brand Anzick ($499)

My wife and I have been using one of these regularly since May, supplanting all other knives in our kitchen. We cook almost all our meals, and this sucker is still sharp. It’s also sturdy enough that it’s on the packing list for both a three-week holiday trip to our cabin and a three-month camping trip to Baja Sur and back next year.

For Your Pocket: CRKT Redemption ($225)

Legendary knife designer Ken Onion’s take on an Old West boot dagger, this thing is more fun to fidget with than it is practical, but it is still a very pocketable blade that you can flick open and cut stuff with. It also feels like it costs a lot more money than it does thanks to the sturdy stainless steel and G10 handle.

For The Outdoors: Montana Knife Company MagnaCut SpeedGoat ($225)

Small, slim, and lightweight, this thing is my constant companion in the backcountry. That’s due as much to the excellent sheath as it is to the blade itself. Much less bulky than similar sheaths from other companies, this one allows you to mount the knife tip-up to a pack strap, horizontally to a belt, or in the traditional tip-down belt hang. Across two weeks spent in a skiff on the Prince William Sound, the knife didn’t develop a single spec of corrosion.

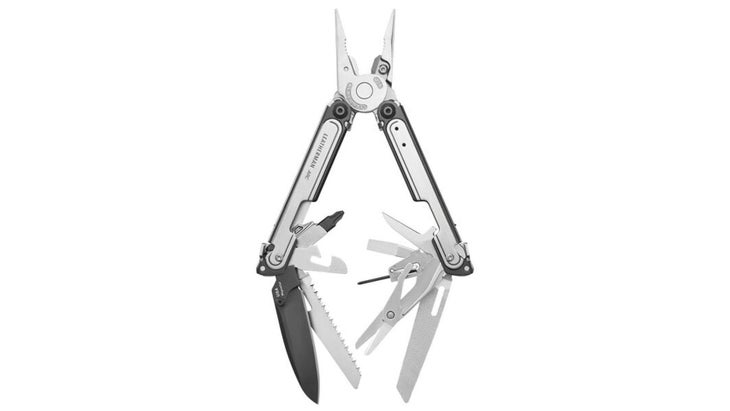

For Fixing Stuff: Leatherman Arc ($230)

Easily the sexiest multitool ever made, this thing is also immensely practical thanks to two bit holders, a redesigned awl, a diamond-like coating on the file, and of course that strong, sharp, easily accessible MagnaCut blade.

Source link