No products in the cart.

Outdoor Adventure

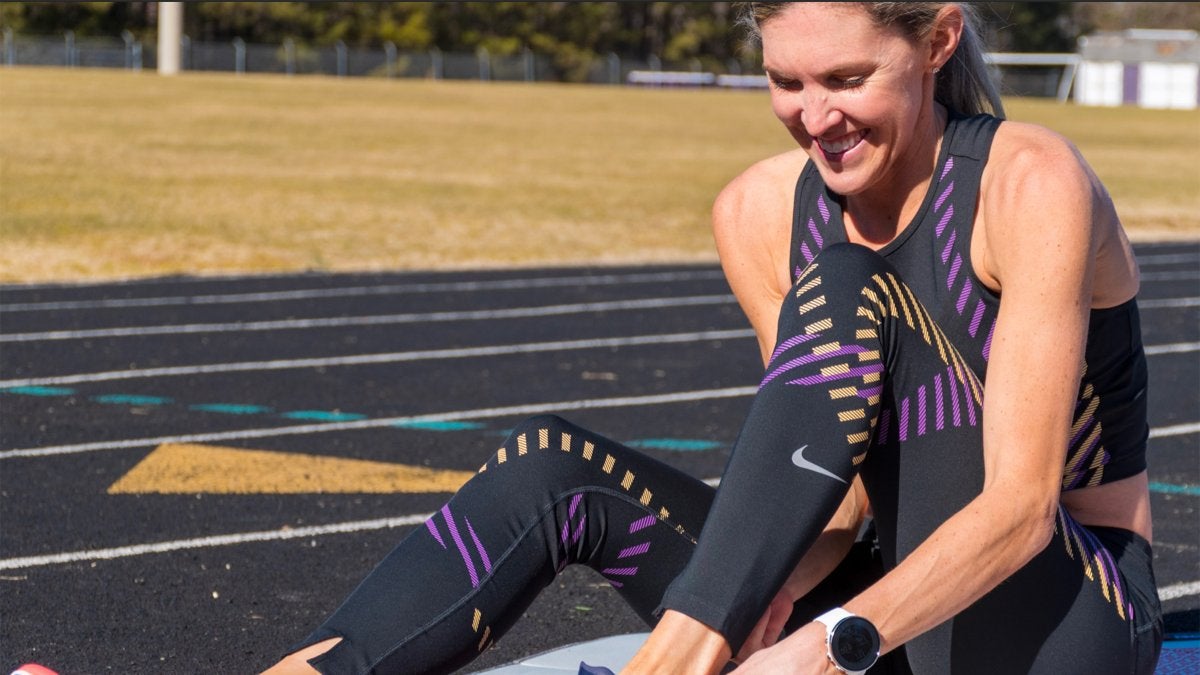

Why Running’s Fastest Amateur Just Went Pro

Earlier this month, the American distance runner Keira D’Amato announced on Instagram that she had signed with Nike. At first glance, this may not seem particularly noteworthy. By any measure, D’Amato had a breakout year in 2020. In a remarkable display of range, she ran a 15:04 5K time trial in June and a 2:22:56 marathon at the Marathon Project race last December—both massive personal bests that, for context, are well inside the tough Olympic qualifying standards. In November, at the Up Dawg Ten Miler in Washington D.C. D’Amato ran 51:23—an American record for a women’s-only ten mile race. No wonder Nike was interested.

But what sets her apart from athletes like Sara Hall and Aliphine Tuliamuk, both of whom also had standout performances in 2020, is that D’Amato was competing as an amateur. Now 36, D’Amato has a full-time job as a realtor at a Virginia-based brokerage. In the mid-aughts, she was a star runner at American University, but an ankle injury and subsequent surgery forced her to walk away from the sport in 2009. It was only after the birth of her second child, in 2016, that D’Amato began training again. She ran her first marathon in 2017, finishing in 3:14:54.

Her progress since then has been astounding. While there have been other stories of amateur runners producing professional-caliber performances, it’s difficult to overstate just how fast D’Amato’s times are—especially considering that they came during a year where high-level competition was hard to find. Having catapulted herself into the upper ranks of U.S. distance running, her goal for 2021 is to make the U.S. Olympic team in either the 5K or the 10K. Or both.

I spoke to D’Amato about her Olympic aspirations, the benefits of sponsorship, and reaching her athletic peak in her mid-30s.

OUTSIDE: After your performances in 2020, there was a lot of talk about how it was unbelievable that you didn’t have a pro contract. Others pointed out that, since you had a “normal” job, it was perhaps a competitive asset that you didn’t face the financial pressure of having to earn a living as a pro runner. How do you feel about that now that you have officially joined the pro running ranks?

D’AMATO: I aspired to be a professional athlete from a young age, so I feel very proud and excited that I’ve found a partner to bring me to that level, but I was really hesitant to go down this road because I didn’t want anything to change. Everything I was doing was working. It was kind of like: “Why rock the boat, when doing it my way has worked for me?” And I think my way entailed being a realtor and keeping a lot of the pressure off running. But Nike didn’t ask me to change anything, other than now being officially sponsored by them. I’m staying with the same coach who brought me here. My primary source of income is still real estate. I feel like I’m supporting my family and, with running, I have the freedom to take risks. When the goal is just: “How fast can I run?” it makes things a lot easier.

Aside from the extra income and free gear, are there additional perks to professional sponsorship?

It’s great to now have a budget specifically for things like a chiropractor and physio. That also takes the financial burden off my family. Having a budget for traveling also makes decisions about which races to run a lot easier. Before it was like, “Do I want to travel for this race if it’s going to cost us this much?” Having a contract takes that factor out of the equation. The gear is awesome, too.

I know a lot of runners who picked up running again in their mid-30s after an extended hiatus. Those who competed in college generally aren’t able to regain the raw speed they had when training at a high level in their early 20s. Their 5K PRs are forever out of reach. But not you. According to the internet, your college PR is 16:09. You ran more than a minute faster last year. What’s the secret to unlocking such speed? Asking for a friend.

I think that part of my secret is just that I’ve always had natural speed. I was a miler in high school and in college. But I think my secret sauce has been my coach Scott Raczko. He has trained me for a marathon in a way that has really developed my speed. Before I started training with him, my 5K pace was pretty much my marathon pace. I feel like a lot of people approach marathons purely from the strength side. I think that’s one way to do it. But I think I’m proving that training for marathons from a speed perspective can be equally as effective. I put everything on Strava and on some of my workouts I get comments asking if I’m training for a 5K or a marathon. The first workout of every marathon cycle for me is 200-meter repeats. It kind of just pulls everything along if you start off running fast. If I can get comfortable running 200s at 32 seconds, I can get comfortable running 400s at 66 seconds. And that makes running a mile in the 4:30s comfortable. Which then pulls down my 5k and 10k times.

You’ve said that you hope to make the Olympic team in either the 5K or the 10K. Possibly both. Do you feel more confident in one distance than the other?

I think that my marathon time makes me feel a little more confident with the 10K, but I haven’t had an opportunity to really race either of the shorter distances. I think there’s so much more in the 5K that I haven’t shown yet, so both distances really excite me. I think both are going to be great this year. Since my 5K and 10K times last year were either on the road or in unofficial time trials, I still need to qualify for the U.S. Olympic Trials in June. Which is OK by me, because I’m going to need to be able to run that fast if I want a shot at making the team. I know I’ll hit the qualifying times, so I don’t feel any sort of pressure to rush that in. But I’ll be racing the 10K at a meet in Austin, Texas, later this month.

In an article in Runner’s World, you mentioned that getting back into running at this stage in your life gives you a chance to pursue “unfinished business,” and that making an Olympic team was always your ultimate aspiration as a runner. This might be an obvious question, but what is it that’s so validating about becoming an Olympian, as opposed to, say, setting an American record?

I think it’s because people who know nothing about running still know what an Olympian is. The event is on such a world stage that it is the pinnacle of so many different sports and competitions. I can’t really describe why that means so much more to me personally, but just that you have so many different countries in different disciplines coming together to compete in one arena is just special. How cool would it be to have the term Olympian next to your name for the rest of your life? People can take your American record away, but never the status of being an Olympian.

Now that you’re gearing up for racing on the track, do you remember the first workout you did in spikes since returning to the sport? Was there a rush?

The first time I put spikes on since 2008 was actually two weeks ago. I did some sprints. It feels wild. You can just feel the track and connect to it in a way that you don’t when you’re running in flats. It’s definitely invigorating. It’s a cool feeling. Energizing. I feel fast, man. I’m excited to race now.

Lead Photo: Linda D’Amato